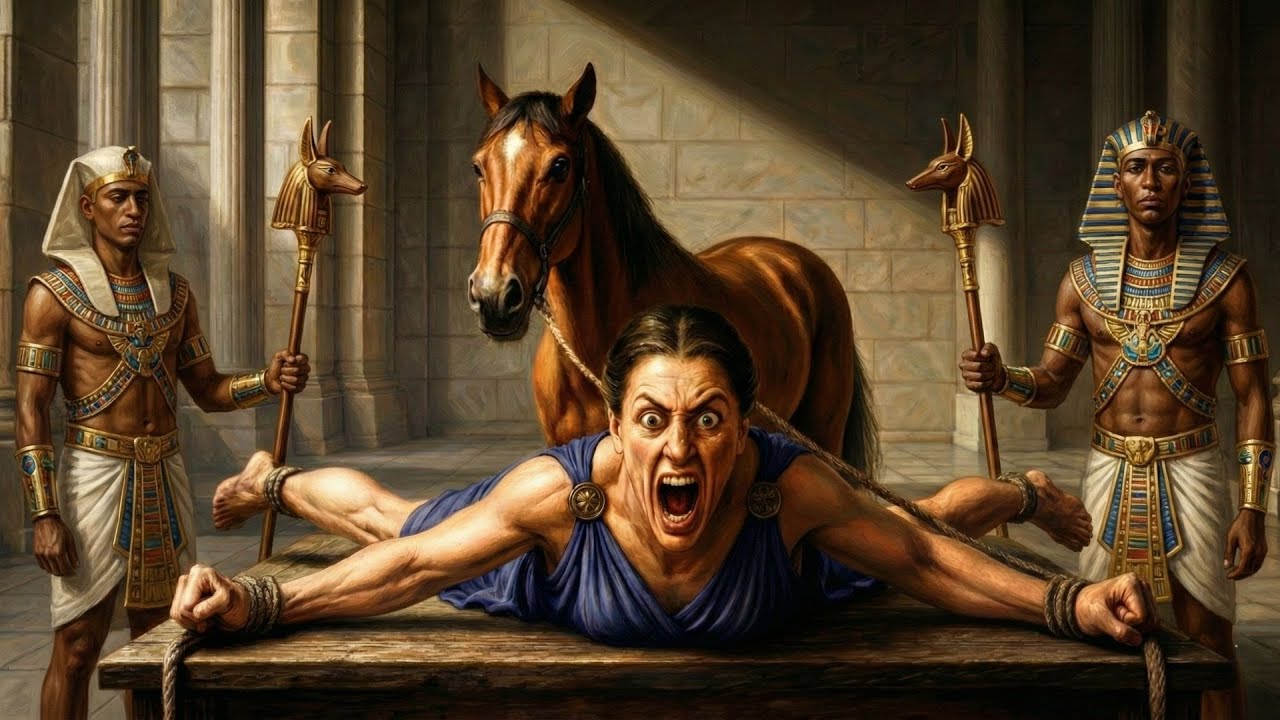

The depraved rituals that Egyptian priests performed on virgins in the temple made them want to erase them from history.

The year is 1184 BC, in the city of Thebes. The sun falls like a spear upon the colossal columns of the Karnak temple. If you go there today, you will see tourists cooling off in the shadow of those pillars, people taking photos of hieroglyphs with the latest cameras. Guides will tell you how magnificent these structures are, speaking of the power of pharaohs, the marvel of engineering, and the splendor of Egyptian civilization. You touch those stones and feel the coldness of thousands of years ago at your fingertips. What you see is civilization, art, and respect for the gods, but if those stones could speak, the story they would tell you would not be of the pharaoh’s victories or architectural triumphs. Those stones would tell you of the silent screams that echoed in the flickering shadows of oil lamps when night fell and the temple doors were shut. Today, right here, we are going to talk about a crime against humanity hidden behind history’s most magnificent showcase: a systematic nightmare covered in gold dust and sacred tradition. If you believe that history does not consist only of fables written by the winners, and that there are tears of the innocent in the mortar of magnificent monuments, you are in the right place.

Our story begins with a 10-year-old girl named Iset. Iset was a child living in her own little world in a humble mudbrick house on the west bank of the Nile. Her father, Horry, was a stern but hardworking farmer. Her mother, Tia, was a woman with calloused hands who washed clothes by the river and baked bread all day. Iset’s life was simple: chasing geese by the river in the mornings, helping her mother, and listening to old stories told by her father under the stars in the evenings. But that year, the Nile had not been as generous as expected. The waters did not rise enough during the great inundation, the fields were not saturated, the harvest was scorched, and the earth had cracked. Iset’s father could not pay the debt for the seed grain he had taken from the temple at planting time. In Egypt, temples were not just places of prayer; they were the giant banks, ruthless tax officers, and largest landowners of the day. And the priests of the temple of Amun were not as patient about collecting their dues as the gods they worshiped. The debt had to be paid: either with silver, with grain, or with blood.

Iset never forgot that morning. Her father had dressed her in her cleanest dress and combed her hair with care. Iset thought this was a holiday visit. “You are a chosen one, Iset,” her father had said, his voice trembling. “The gods are accepting you into their home. There, you will never go hungry. You will not work under the sun. You will have a sacred life.” It was impossible for a 10-year-old child to fully understand that evasive look in her father’s eyes, the shame, the head bowed low, and the trembling hands. When they arrived at the colossal gate of Karnak, which reached for the skies and made a human feel like an insect, Iset held her father’s hand tighter. The priests at the gate were men in white linen, clean-faced but with cold eyes. As they took custody of Iset, they handed her father a clay tablet—a receipt, yes, you heard that right, a simple bureaucratic document stating that a debt of 10 sacks of grain was wiped out in exchange for a girl-child. As Iset watched her father turn his back and walk away, and watched those massive cedar doors plated in bronze close with a thunderous noise, she did not yet know that her childhood had remained behind those doors as well. The only thing she felt at that moment was that huge cold lump sitting in her stomach and the sharp pain of abandonment.

From the moment she stepped inside, Iset’s senses were under attack. After the dusty, noisy, and hot air outside, the interior of the temple was cool, dark, and smelled heavy. The scent of myrrh, frankincense, burnt oil, and stale flowers that had permeated the walls for centuries burned her throat. The priests did not say “welcome” to her. They did not pat her head. They did not call her by her name. They dumped her like an object beside the other girls—children just like her, eyes swollen from crying, gathered from Nubia, Libya, or the villages of Egypt. All of these girls were to become the temple’s “sacred servants.” Sounds elegant and spiritual, doesn’t it? But the truth lying beneath this title was savage enough to shatter a child’s soul, cruel enough to turn a human into a living corpse.

The first destruction began in the place they called the “purification room,” where the stone walls were green with dampness. This was a dim room, blackened by torch soot, with a pool full of ice-cold water in the center. The priest said, “You cannot appear before God with worldly filth. You will leave the dust of your past here,” and ripped away that simple linen dress Iset was wearing—the last piece sewn by her mother’s hands, carrying the scent of her home. Nakedness is the ultimate point of vulnerability and helplessness for a child. When Iset, trembling with shame, crossed her arms over her chest to protect herself, an old priestess harshly slapped her hands down. “You have nothing to hide,” the woman said, her voice like a whip echoing off the stone walls. “This body no longer belongs to you. It is the property of Amun. Property does not feel shame.” As the ice-cold water was poured over her head again and again, leaving her breathless, Iset began to cry. But even tears were not allowed. Crying was seen as a rebellion against the god, ingratitude for the grace offered. “Wipe your tears,” they said. “Servants do not cry.”

Then came the turn of the most tangible part of identity: the hair. In Egypt, hair was a woman’s, an individual’s most important ornament, status, and part of her personality. Iset’s long black hair, which fell to her shoulders and which her mother combed and braided every morning, was her pride. When one of the priests approached with a curved, cold bronze razor in his hand, Iset tried to pull back in panic. Two strong hands pressed down on her shoulders and forced her to the ground, to the hard stone floor, onto her knees. The scraping sound the bronze blade made on her scalp was a sound Iset would never erase from her ears for as long as she lived. With every lock of hair that fell to the wet floor, another memory from Iset’s past was torn away. As that hair, stroked by her mother and blown by the wind, lay lifeless on the floor in a black heap, Iset did not dare to look in the mirror. When the priest forced her face toward the bronze mirror, the person she saw was not Iset. What she saw there was a slave with a shining skull, eyes wide with fear, genderless, identityless, and with a stolen soul.

But the temple system was not content with just this. After taking her body, they wanted her name too. To take away a person’s name is to deny their existence, their history. The high priest did not even glance at Iset as he entered a new record onto the papyrus scroll in his hand. “Iset is dead,” he said, as if announcing a fatality. “Your name is now Merisamun, meaning ‘Beloved of Amun.’ You will never pronounce your old name again. If you speak it, you will be silenced.” From that day on, Iset tried to remind herself of her own name only at night, in that crowded, airless, sweat-smelling room called the dormitory. Silently, under her blanket, without moving her lips: “My name is Iset. My father’s name is Horry. I do not belong here.” These whispers were the only prayer that kept her sanity intact, that kept her from going mad in this darkness.

Iset found a single light: T. T was a girl brought as spoils of war from a village on the Nubian border two years before Iset, carrying a fire of rebellion in her eyes that had not yet been extinguished. Their bunks were side by side. On the first nights when Iset cried, T reached out and squeezed her fingers in the dark. Talking was forbidden, but glances and touches were more powerful than words. While working side by side in the weaving workshop, they would whisper without moving their lips. T would talk about escape plans. “There is a canal at the base of the south wall,” she would say. “In the dry season, we can pass through there.” Iset was afraid, but T’s courage gave her strength. T would tell her, “They left us hairless, but they couldn’t take our minds. We are still us.” This friendship was the only human thing, the only refuge within those stone walls.

Days, months, and years passed, grinding against each other like millstones. Temple life was not a spiritual journey consisting of hymns and incense, as it appeared from the outside. This was heavy, monotonous, and consuming labor: waking up before dawn, being purified again and again with ice-cold water, then grinding tons of grain in the temple’s massive kitchens, weaving the finest linens in the weaving workshops until eyes went blind and fingers bled. But the heaviest part was the silence. Laughing was forbidden. Singing was forbidden. Hugging each other was forbidden. The temple demanded not just physical labor but absolute spiritual obedience. You were not allowed to be an individual; you were the cogs of a gigantic machine.

When Iset turned 13, she met the darkest, most perverse, and most secret face of the system. The priests called this the “Sacred Marriage.” This term was described so poetically, so sublimely, in papyri and on the reliefs on the temple walls: the god descending to earth, uniting with his chosen servant, preserving the balance of the universe, the sacred union required for the Nile to flood. But when you scraped away those fancy gilded words, the truth underneath was nauseating.

That night, they rubbed Iset with scented oils. They dressed her in a robe embroidered with golden threads as thin as tulle, leaving her skin almost completely exposed. They put a heavy wig adorned with precious stones and a golden crown on her head. When she looked in the mirror, she saw a queen before her, but inside, she was no different from a trembling, trapped prey animal. They took her to the deepest, most secret room of the temple, the Holy of Holies, the intimate chamber where the god’s statue was located. This was a forbidden zone where entry by ordinary people was punishable by death, accessible only to high priests and the pharaoh. The air in the room was so heavy that you couldn’t see through the incense smoke. Shadows created by flickering flames danced on the walls like giant monsters. And in the middle of the room, beside a gold-plated bed, he stood: the high priest of Amun. But at that moment, he was not a man. He wore the ram-headed golden mask of Amun on his face.

Iset had been told that the one before her was not a man but the god Amun himself, and that the body behind that mask had transformed into a divine power. The high priest’s assistant leaned into her ear and whispered, “Do not object. If you reject the god, the Nile will dry up. The sun will not rise. Egypt will perish in famine. The blood of all the people will be on your hands.” Could there be a greater, more savage psychological torture than threatening a child with the destruction of the universe, with the death of all her loved ones?

That night, in that room, Iset had to allow a man in a gold mask to invade her body under the guise of a divine ritual. She separated her mind from her body. She focused on the stones on the ceiling, the paintings on the wall. “I am not here,” she said inwardly. “I am a stone. Stones do not feel pain.” This was the sanctification of rape. This was the cloaking of the most primitive, selfish desires in the guise of religion and tradition. When she walked out of that room in the morning, Iset was no longer that innocent girl. She was walking, breathing, but the light in her eyes had gone out. A part of her soul had died in that room.

When she met T in the temple courtyard, T asked nothing. She just took Iset’s hand and looked into that deep, dark void in her eyes because she knew too. She had been in that room too. She had met that masked god too. This was a silent, shameful, heavy secret shared by all the women there.

A few months later, the time for the great Opet Festival arrived. Outside the temple was chaotic. The people were beating drums, singing songs, dancing. Crowds had poured into the streets to watch the procession of the god statues. Sounds of joy, laughter, and music were surmounting the high walls of the temple and leaking inside. Iset and T were watching outside from the small barred window of the weaving room. That freedom outside, that simple happiness, was so close to them yet so far away.

T could not take it anymore. “I am going,” she said, her eyes shining. “Tonight, in the confusion of the festival, I will escape. You come too.” Iset was afraid. She couldn’t do it. T left that night, and towards morning, a terrible scream was heard in the courtyard. T had been caught. The priests dragged her to the center of the courtyard. They didn’t beat her. They didn’t shout. They did worse: they threw her into the “Cell of Silence.” When T came out of there three weeks later, she was no longer that rebellious girl. Her gaze was empty. She had stopped speaking completely. Her spirit was broken. She never held Iset’s hand again. A few months later, it was said she was summoned to the side of the gods, and she disappeared. Iset never even learned where her friend was buried.

And then the inevitable biological consequence of this nightmare arrived. Iset became pregnant. The priest called this the “Holy Seed,” God’s blessing. As Iset’s belly grew, the turmoil inside her turned into a storm. This child was a fruit of the cruelty done to her, of that masked night. But at the same time, it was her blood, her part. Perhaps within these cold stone walls, this was the only thing that truly belonged to her, the only thing she could love and hold. For nine months, she held on to that movement in her womb. At night, she whispered to it, told it about the floods of the Nile it would never see, the smell of her mother’s bread. A hope sprouted inside her like a frail weed: maybe with this child, she could build a tiny world of her own.

But the temple would not share its property with anyone. When labor pains began, they took Iset to a room called the Mamisi (birth-house), decorated with frightening images of the birth god Bes. Amidst pain, sweat, and blood, when she heard her baby’s first cry, Iset forgot all her pain. After the priest cut the cord and cleaned the baby, they gave it to Iset’s arms for only a moment—for a time measured in seconds. It was a baby girl. Iset touched her daughter’s tiny fingers, inhaled that scent of paradise. And at that exact moment, a rough hand reached out and snatched the baby from her breast. “No!” screamed Iset, her voice shaking the walls of the birth-house, echoing in the courtyard outside. “She is mine! Give it to me!” The priest, without a shred of emotion on his face, without the slightest sign of mercy, wrapped the baby in a harsh cloth and headed for the door. “She is the daughter of Amun,” he said in a cold, metallic voice. “What comes from the god, we give back to the god. Your duty is done, Merisamun. Now rest. You will serve again soon.” Iset tried to get up from the bed, fell to the floor in blood, tried to crawl to the door, but the midwives held her back. Her baby’s crying echoed down the corridor, fading, fading, and finally ceased completely with the closing of a heavy door. The scream Iset let out that day permeated the stones of the temple, but no one heard.

The right to motherhood had been erased, like an erroneous entry deleted from an inventory ledger, like a debt wiped from a merchant’s book. Her child, if a girl, would be raised to be a servant, just like her mother. If a boy, he would become a part of that cruel system—a priest. This was a horrific cycle that fed itself: victims gave birth to new victims and new executioners.

Years passed. Iset grew old and rotted within the stone walls of the temple. Her body collapsed from heavy labor, malnutrition, and successive births. Her hair—that hair never allowed to grow—now came out gray when shaved. The calluses on her hands had ossified. Sometimes, in the temple courtyard, she would see young girls newly arrived, children, eyes full of fear, hair freshly shaved, crying. As she looked at them, her heart would clench. She wondered which one was her daughter, which one was her granddaughter. She searched for someone of her own blood in that crowd. But she never knew. She could never approach them and say, “Don’t be afraid, I am your mother,” because that meant death. The vow of silence could not be broken.

Iset and thousands of women like her buried not only their bodies but their minds, their memories, their laughter, and their futures in that temple. However, the human spirit refuses to completely vanish no matter how crushed it is.

In the last days of her life, lying sick and exhausted, Iset found a small crack in the wall in a dark corridor of the temple used as a storage room where no one visited. With a sharp piece of stone she’d found, she began to carve something into that hard limestone with hands that had secretly learned to write hieroglyphs. This was forbidden. The punishment was death. But she no longer cared. With trembling hands, in simple, crude lines, she carved the sentence: “My name is Iset, daughter of my father Horry. I lived. Do not forget me.” This was not a prayer. This was not a plea to a god. This was a letter left to the future, a proof of existence, a challenge. It was the indelible truth carved by a woman’s fingernails against the priest’s gold-plated history full of lies.

When Iset died, no ceremony was held. No one cried for her. Her body was thrown into the nameless cemetery behind the temple, into that mass grave pit at the edge of the desert beside hundreds of other servants. Lime was poured over it, and the earth was hastily covered. In the official records, it was written: “Merisamun, servant, died of natural causes.” But the truth remained hidden on the wall of that dark corridor, in that small, frail scratching.

Today, when you go to those temples, pause for a moment before getting carried away by the heroic stories told by guides, by the victories of pharaohs. Touch those colossal columns, those magnificent statues, that awe-inspiring art, and remember Iset. Remember T. Remember those women whose hair was forcibly shaved, whose names were taken, who were abused under the name of sacred, and whose children were stolen from their arms. Because history is not just the story of those who erected the monuments, but also of those crushed in the shadow of those monuments, those who carried those stones on their backs. When we look at those stones with admiration, we are actually touring a crime scene.

We, as historians, will continue to delve into the depths of dusty archives to bring to light these bitter truths that are covered up, swept under the rug, and hidden by the mask of sacred tradition. If watching this video has awakened anger, sadness, and a curiosity for the truth inside you, this is just the beginning, because there are thousands more silent screams to be told, thousands of unfinished stories waiting beneath the sands. We need your support so that these voices can ring louder, so that the stories of forgotten women like Iset can reach millions and so that we can confront this dark face of history. Please like the video and subscribe to the channel and share your thoughts in the comments. Do you think there are still similar institutionalized cruelties hidden under the names of sanctity, tradition, or necessity in the modern world? Come, let’s discuss below. Remember, the past is never truly dead. It only waits for someone to dig it out from under the earth and tell it with courage. See you in the next video, in another dark corridor of history. Stay in pursuit of the truth. Goodbye.

News

What the Ottomans did to Christian nuns was worse than death!

What the Ottomans did to Christian nuns was worse than death! Imagine the scent of ink from ancient parchments still…

The Whitaker Boys Were Found in 1984 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans at All

The Whitaker Boys Were Found in 1984 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans at All The Blackwood National Forest…

The Pike Sisters’ Breeding Barn — 37 Missing Men Found Chained (Used as Breeds) WV, 1901

The Pike Sisters’ Breeding Barn — 37 Missing Men Found Chained (Used as Breeds) WV, 1901 In the summer of…

The Plantation Owner Gave His Daughter to the Slaves… What Happened to Her in the Barn

The Plantation Owner Gave His Daughter to the Slaves… What Happened to Her in the Barn In the summer of…

The Horrifying Wedding Night Ritual Rome Tried to Erase From History

The Horrifying Wedding Night Ritual Rome Tried to Erase From History Imagine being 18 years old, dressed in a flame-colored…

GOOD NEWS FROM GREG GUTFELD: After Weeks of Silence, Greg Gutfeld Has Finally Returned With a Message That’s as Raw as It Is Powerful. Fox News Host Revealed That His Treatment Has Been Completed Successfully.

A JOURNEY OF SILENCE, STRUGGLE, AND A RETURN THAT SHOOK AMERICA For weeks, questions circled endlessly across social media, newsrooms,…

End of content

No more pages to load