Sisters who were their own father’s lovers – Never Tell the story of the weavers’ heiresses

Spring of 1951. Nestled among the gently rolling hills of the Swabian Alps, where dense forests smell of resin and the wind sweeps across vast orchards, stood the sprawling Sonnenbruck farm. A farmstead of dark timber framing and heavy slate roofs, it had belonged for generations to the Weber family, a respected and wealthy dynasty.

whose name was almost as deeply rooted in the region as the old beech trees on the slopes. But behind the walls of the farmstead, whose beams glowed warmly in the evening light, lay a secret as deep and rotten as the clay soil beneath the cellar vault. A secret that remained buried for decades until one day it broke under its own weight, like a moldy beam.

The owner, Friedrich Weber, had been a widow for five years. Since the death of his wife, Anna Weber, who had succumbed to pneumonia in the bitterly cold winter of 1946, the once generous and friendly farmer had changed. He was a tall man with silver-gray hair and piercing blue eyes that had always radiated warmth but now carried something icy and controlling.

He was rarely seen smiling, and when he did, it never seemed genuine. His three daughters lived with him in the large main house. Kara, the eldest, was [age], classically beautiful, with full lips and green eyes that had once shone with joie de vivre. Helen, 21, was wilder, more spontaneous, with raven-black hair and a manner that made young men everywhere nervous.

And Lena, the youngest, was [age], a girl with a pale, almost fragile grace that awakened a protective instinct in every villager. All three had received an excellent education at the Benedictine convent school in Boyon. They played the piano, spoke fluent French, and were renowned for their impeccable manners and flawless appearance. But since their mother’s death, they had never been the same.

Something about them had changed. The inhabitants of the nearby village of Lindenweiler whispered in the inns that the girls hardly ever left the house anymore, that they met every suitor with cold indifference, that they lived in a strange seclusion, as if the Sonnenbruck farm were a world unto itself,

one into which no outsider was allowed to look. The village priest, Father Johannes Ritter, a man with a round face and kind eyes, was the first to sense that something was wrong. In his later discovered notes, he wrote: “Since the death of Frau Anna, a shadow has hung over the farm. The girls seem frightened, almost withdrawn.

And there is a heaviness in their gaze that doesn’t suit their young age. When I speak with them, they seem to know more than they are allowed to say. Something unspeakable hangs between them.” Friedrich Weber himself had transformed in those years into a man whom many hardly recognized.

He dismissed all the male farmhands who had worked faithfully for the family for decades and replaced them with older women from neighboring villages. His justification was that he wanted to protect his daughters. But the truth was much darker. One of the women who later testified during the investigation was Margarete Hauf, the farm’s former cook. Her words were recorded verbatim in the archives of the Tübingen District Court. “

Mr. Weber looked at his own daughters in a way that made my stomach churn, especially clearly. I knew immediately that it wasn’t a father’s look. There was something possessive, impure about it. I couldn’t prove it, but I felt it.

At night, I sometimes heard noises from upstairs—footsteps, doors, and sometimes wine.” The summer of that year brought the first rumors, which jumped through the region like poisonous sparks. People whispered about impure things, about arguments, about the girls’ strange absence from village festivals. Some noticed that Friedrich no longer let the three practical girls out of his sight.

Even at church, he held them so close that it was almost painful. And he always had a hand on the arm of one of his daughters. Too long, too tight, too possessive. No one suspected then that this was only the beginning, the beginning of a story that would later be filed away in secret as the case of the cursed heiresses of Sonnenbruck.

What happened that spring in the Swabian alpine garden was a horror that would soon shake the entire region and eventually all of Germany. The first indication that something beyond imagination was happening at the Sonnenbruck farm surfaced in August 1951. On a rainy Tuesday morning, the Reutlingen district office received an anonymous letter.

The paper was damp, the ink smeared, the writing shaky, as if the writer had written in great fear. The message consisted of only a few lines: Things against nature were happening at the Weber farm. The three girls were in danger. Please act before it’s too late. The letter was filed away but no further action was taken.

The Weber name was too powerful. The family dominated the region too much, and no one wanted to antagonize Friedrich. But the silence didn’t last long. The village midwife, Anna Maria Fink, an experienced woman with a keen eye, was summoned to the Sonnenbruck farm three times in the middle of the night that autumn, officially to attend to the daughters’ gynecological illnesses.

But what she found there haunted her for the rest of her life. In her later testimony in court, almost three years after the scandal, she described: “Kara showed clear signs that she had given birth not too long ago, and secretly at that. And with Lena, I recognized symptoms that I had previously only seen in women who had undergone major surgery.” When I asked questions, Mr. Weber became furious.

He threatened me, told me to watch my tongue, or I would lose my job and my reputation along with it. Meanwhile, the atmosphere in the village remained somber. Sunday Mass, once a gathering place for laughter and whispers, had become a scene of furtive glances.

The three Weber sisters appeared every week dressed in deep black with veils that concealed their faces. They sat in the front row, right next to their father. But unlike before, they never received communion. They left the church immediately after the final blessing. Father Johannes wrote in his records: “They seemed like three shadows, not like young women praying, but like sinners serving a sentence.

“Friedrich’s behavior also became increasingly strange. He personally accompanied his daughters to the baker, the post office, and even to the tailor in the next town. If anyone tried to start a conversation with them, he would block their way. Physically, threateningly. It seemed as if he wanted to keep the girls entirely to himself.

The shopkeeper, Karl Friedrich Rombach, later testified that he stood so close behind them that I felt uncomfortable. He stroked Klara’s hair, adjusted Helene’s scarf, and touched her shoulders in a way that immediately struck me as wrong. I swear, that wasn’t fatherly. But the most profound insight came from a young woman named Elisabeth Lisel Krötz, who was the only farmhand to manage to stay on the farm for more than six months.

Her detailed testimony was later considered a key piece of evidence in the entire trial. She reported: “I heard no noises, not like footsteps, more like sobs, breathing, sometimes even something that sounded like whispering. Once I went to the kitchen to get water.” Then I saw Mr. Weber coming out of Klara’s room. He was buttoning his shirt.

Klara stood in the doorway, in her nightgown, pale and with tears on her face. I knew immediately that I had seen something I shouldn’t have. He shouted at me to get lost, but I’ll never forget that image. The medical records of Dr. Wilhelm Krämer also gave cause for concern.

Between spring and winter 1951, he treated the sisters for severe nervousness, depressive mood, irregular menstrual cycles, and unexplained physical exhaustion. In his private notes, which his family only published after his death, he wrote: “The three girls are under enormous psychological pressure. Klara suffers from nightmares. Helen has deep scratch marks on her arms.

Lena seems like a frightened animal. Every time I ask about the cause, they stare at the door as if someone expects them to be silent. By winter, their isolation was complete. They didn’t participate in any village festivities. They no longer showed themselves to friends. They rarely answered when seen on the road.

The residents of Lindenweiler began to watch the shutters of the farm. Sometimes lights flickered at night, sometimes distant screams were heard, which immediately ceased. But no one dared to enter the Sonnenbruck farm. No one asked questions.

The horror had taken shape, but no one yet knew how great it truly was. What would follow in winter would dwarf everything heard before. The winter of 191 arrived early and harshly upon the Swabian Alps. Snow fell in thick, heavy layers.” Snowflakes that completely cut off the Sonnenbruck farm from the outside world within a few days.

The paths were impassable, the telephone lines repeatedly failed, and the already isolated farm became a fortress of frost and silence. It was precisely during this period of enforced confinement that the horror reached its peak. The only woman still on the farm during this time, the young Petra Altdorfer, later left in a state of near-madness and provided investigators with the most horrific accounts of those months.

In her statement, which was recorded verbatim in the district court, she said: “Mr. Weber had a strict routine. Every evening at precisely 8 o’clock, he sent me and the old washerwoman to our rooms. We weren’t allowed to open the doors, no matter what we heard. But the walls were thin, and the courtyard was quiet, too quiet.

I heard Klara pleading, I heard Helene crying. Sometimes I also heard Mr. Weber, panting, hissing, muttering like a man possessed.” Meanwhile, Dr. Krämer documented a drastic decline in the sisters’ mental health. Kara, once self-assured and elegant, developed a severe anxiety disorder.

She hardly ever left her room anymore, standing trembling at the window for hours, as if waiting for something invisible outside. According to medical records, Helene began speaking about herself in the third person, as if observing her own life like a stranger. She is in pain; she mustn’t scream. Otherwise, he will hear it. Lena, the youngest, exhibited self-harm.

She tore out clumps of her hair, She refused to eat and sometimes stared for minutes at a time into a dark corner of the room, as if she saw something or someone that others couldn’t see. Then, in February 1952, the event occurred that would later be known simply as the Night of the Bloodstains. The former cook, Margarete Hauf, who was called back to the court for an emergency, described the following: Klara was heavily pregnant, but something was wrong.

Her belly was too large, too heavy, her face ashen-faced. She was trembling, constantly talking in her fever: “God is punishing us, heaven sees everything.” When the contractions started, I wanted to call the doctor immediately. But Mr. Weber grabbed my arm and said: “No strangers are allowed in the house. This is a family matter.”

I had to go through the whole process alone, and what was born that night was not normal, not healthy, not human, as it should have been. The official records omit the details. Every line relating to the newborn was redacted by the Interior Ministry. However, everyone present left hints in private notes.

The medical examiner later wrote, drunk and distraught: “I saw things God never intended.” Klara’s child lived for only a few hours. No one knew where Friedrich took the small body. But in the spring, several fresh, shallow burial mounds were discovered on the snow-covered grounds of the farm, which were never officially investigated. During this time, Helene completely lost touch with reality.

Petra Altdorfer recounted: “I found her once in the courtyard in the middle of the night. Barefoot in a thin nightgown in the icy snow. She was kneeling in the storm, digging a hole with her bare hands. Her fingers were sore and bloody. She was muttering Latin sentences backward. When I tried to touch her, she screamed: ‘I have to bury him. I have to put the evil back in the earth.

’” At the same time, several unusual payments appeared on Friedrich Weber’s bank statements, large sums of money to unknown individuals. Furthermore, medications were procured in quantities that could only indicate that procedures, abortions, and forced abortions were becoming increasingly frequent. But the decisive turning point came on

April 15, 1952, when Lena, the youngest, dared the impossible. At a moment when Friedrich was completely focused on Kara, whose condition had become critical, Lena climbed out of a side window of her room and ran barefoot across frozen ground. Five kilometers, through forest, over icy fields, pursued only by her own racing heartbeat.

She reached the Benedictine convent shortly after midnight and collapsed in the entrance hall. The nuns later reported that she looked like a trapped animal that had escaped and didn’t yet know whether it was free or lost. Her clothes were torn, her feet were bleeding, her lips were blue with cold, but worst of all were her eyes, two large, empty mirrors filled with fear.

When she had been cared for and was finally able to speak, she uttered only one sentence: “My father is no longer my father.” And these words were only the beginning of that shattering confession that would shake Germany to its core. Lena Weber was brought that night, half-conscious, to the small infirmary of the Benedictine convent.

Sister Agatha, the most senior nun, later recounted that the girl trembled like someone who had lain in the snow for days. Her lips quivered constantly, her hands clenched tightly in the blanket as if she feared someone would pull her back at any moment.

News

GOOD NEWS FROM GREG GUTFELD: After Weeks of Silence, Greg Gutfeld Has Finally Returned With a Message That’s as Raw as It Is Powerful. Fox News Host Revealed That His Treatment Has Been Completed Successfully.

A JOURNEY OF SILENCE, STRUGGLE, AND A RETURN THAT SHOOK AMERICA For weeks, questions circled endlessly across social media, newsrooms,…

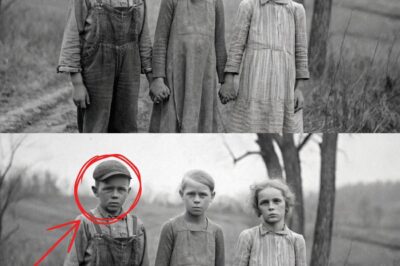

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own The year was 1883,…

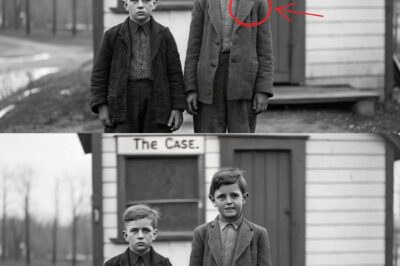

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist…

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart “Get your filthy hands…

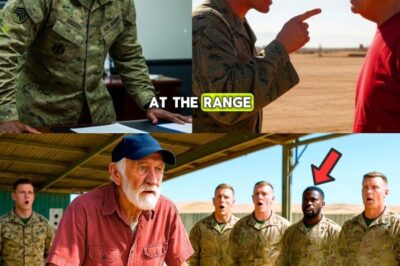

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how.

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how. “Is this a joke?” barked…

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist….

End of content

No more pages to load