Shadows in the Dust: The Silent Struggle of Chaplin’s Coal Children

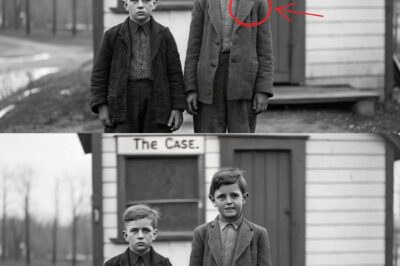

In the annals of American history, there are images that shout, and there are images that whisper. But then there are photographs like the one captured in Chaplin, West Virginia, in 1938, which do neither. Instead, they seem to wheeze—a labored, heavy breath of existence that rattles deep in the chest. This photograph of two children sitting on the porch of a miner’s shack is not merely a document of poverty; it is a forensic piece of evidence detailing a way of life that ground human beings down into the very dust they were forced to inhabit.

The year 1938 was a pivotal moment in the American narrative. The Great Depression had supposedly peaked, yet its aftershocks were still violently shaking the foundations of rural America. While cities were beginning to see the faint glimmers of industrial recovery, the hollows of Appalachia remained trapped in a suffocating twilight. Here, in the coal camps, the “New Deal” often felt like a rumor, and the reality was a brutal cycle of labor, debt, and endurance. To understand this image is to understand the machinery of a system that burned coal to light the world while leaving its own people in the dark.

The Architecture of Despair

The first thing that strikes the viewer is the texture of the environment. The children are framed by wood, but it is not the sturdy, polished oak of the American Dream. It is rough-hewn, splintered, and rotting. The house they sit in front of is a “company house,” a structure owned not by their parents, but by the coal corporation that employed their father. These homes were typically built cheaply and quickly, designed to provide the bare minimum of shelter for the maximum number of workers. They were often uninsulated, meaning the biting Appalachian winter winds whistled through the cracks in the walls, and the humid summer heat turned the interiors into ovens.

The porch, where the children rest, is in a state of advanced decay. The boards are uneven, patched with scrap wood in a desperate attempt to keep the structure sound. The walkway leading up to it is jagged and treacherous, a physical manifestation of the precarious path these families walked every day. One misstep—a broken leg, a twisted ankle—could mean a doctor’s bill they couldn’t afford, or worse, an inability to work.

The overgrown grass in the yard is another subtle but telling detail. In a middle-class suburb, overgrown grass might signal laziness. In a coal camp, it signaled exhaustion. When a mother spends her entire day scrubbing coal soot out of clothes by hand, cooking meager meals from scratch, and trying to stretch a dollar that doesn’t exist, and a father spends twelve hours underground inhaling darkness, manicuring a lawn becomes an impossible luxury. The environment is wild and untamed because the people living in it have no energy left to tame it.

A Girl in a Cloud of Dust

The emotional anchor of this photograph is undoubtedly the younger child, the girl. She sits barefoot, her small feet vulnerable against the rough wood. But it is her hands that break your heart. She is rubbing her eyes. To a modern parent, a child rubbing their eyes might signal nap time. In Chaplin, West Virginia, in 1938, it signaled something far more sinister: the omnipresence of coal dust.

In these mining towns, the dust was inescapable. It wasn’t just in the mines; it was in the air, in the water, on the bedsheets, and in the food. It was a fine, gritty powder that coated everything. For children, this meant chronic eye irritation, respiratory issues, and a constant, gritty discomfort. The girl isn’t just tired; she is likely in pain. The particulate matter from the mines and the unpaved roads would sting and burn, a constant reminder of the industry that owned their lives.

This simple gesture of rubbing her eyes serves as a horrifying metaphor for her future. She is trying to see clearly, but her vision is obscured by the byproduct of her father’s labor. She is growing up in a world where the very atmosphere is hostile to her health. Trachoma and other eye infections were rampant in these communities due to poor sanitation and the constant irritation of dust. This little girl, in her innocent discomfort, represents the physical toll exacted on the most vulnerable members of the mining community.

The Boy and the Burden of the Overalls

Beside her sits her brother. He is older, perhaps seven or eight, and he wears the uniform of his caste: denim overalls. They are likely hand-me-downs, baggy and ill-fitting, meant to last him through growth spurts until they inevitably fall apart. But the overalls are significant. They are the clothing of labor. Even at rest, he is dressed for work.

His posture is strikingly different from his sister’s. While she reacts to the immediate physical irritation, he seems lost in a deeper, more existential fatigue. He leans back on his elbows, staring out into the yard or perhaps at nothing at all. There is a heaviness to him that should not belong to a child his age. In mining families, boys were forced to grow up with terrifying speed. They knew from a very young age that their education would likely end early, replaced by a spot in the breaker boys’ line or, eventually, a trip down the shaft.

He sits on the threshold of the home, a liminal space between the domestic safety of his mother’s kitchen and the harsh reality of the outside world. He looks like a miniature adult, stripped of the carefree energy of childhood. He knows the struggle his parents face; he hears the hushed conversations about debt and the company store; he sees the black rings under his father’s eyes. He is inheriting a legacy of hardship, and the weight of it is already pressing down on his small shoulders.

The Invisible Chains of the Company Town

To fully grasp the tragedy of this image, one must understand the economic prison these children were born into. Chaplin was likely a variation of the “company town” model. In this system, the mining company owned everything: the house, the school, the church, and most importantly, the store. Miners were often not paid in U.S. currency but in “scrip”—metal tokens or paper credit that could only be spent at the company store.

This created a feudal system of entrapment. The company store often charged inflated prices for basic necessities like flour, sugar, and shoes. A miner might work a sixty-hour week, only to find that after his rent, tool rental fees, and doctor fees were deducted, he actually owed the company money. This debt peonage meant that families couldn’t simply leave. To leave was to default on debt, which could lead to eviction and blacklisting.

The dilapidated state of the house in the photo is a direct result of this system. Why would a family invest time and money they didn’t have into fixing a porch they didn’t own? They lived with the constant threat of eviction. If the father was injured, fired, or killed in the mines—a common occurrence—the family would be thrown out of the house within days. This impermanence bred a sense of anxiety that permeated the household. The rotting wood isn’t just structural failure; it is a symbol of their lack of agency. They were tenants in their own lives.

The Phantom Presence of the Parents

Though the children are the only subjects in the frame, the presence of their parents is felt intensely. The father is the reason they are there. He is the invisible engine of the picture, likely miles beneath the earth at the very moment the shutter clicked, chipping away at a seam of coal in the dark, damp, and dangerous tunnels. He risks rock falls, methane explosions, and the slow suffocation of Black Lung disease to put food on the table. The boy’s overalls are a mirror of the father’s work clothes; the coal dust in the girl’s eyes is the residue of the father’s trade.

The mother’s presence is seen in the survival of the children. She is the one who likely patched the boy’s overalls, who swept the porch even though it would be covered in soot again an hour later, who scrubbed the children’s faces. In 1938 Appalachia, a miner’s wife had a job arguably as hard as the miner’s. Without running water—a luxury few company houses had—she would have to carry water from a creek or a communal pump. Heating water for baths, cooking on a coal stove that required constant tending, and fighting a never-ending war against the filth of the mine required a Herculean effort.

The fact that the children are sitting still, reasonably clean (despite the dust), and clothed is a testament to the mother’s sheer will. She is holding the chaos at bay, creating a pocket of humanity in an inhumane environment. The overgrown grass and the broken walkway are not failures of the parents; they are the battle scars of a war against poverty where the enemy has unlimited resources and the family has none.

A Diet of Scarcity

Looking at the children, one cannot help but wonder about their health beyond the dust. In 1938, malnutrition was a silent stalker in West Virginia. The “company store” diet was high in starch and low in nutrition. Families survived on “bulldog gravy” (a mixture of flour, water, and grease), pinto beans, and cornbread. Fresh vegetables were a seasonal luxury, often grown in small garden patches if the soil wasn’t too toxic from the mining runoff.

The boy’s slight frame and the girl’s fragility hint at this nutritional deficit. They are surviving, but they are not thriving. Their bodies are being built on a deficit, which would have long-term consequences for their development and immune systems. The poverty captured here is physiological; it is written in their bones and blood.

The Soundscape of Silence and Fear

If photographs had sound, this one would be filled with a specific kind of quiet. It is the silence of waiting. Mining families lived in a state of perpetual, low-level dread. The town’s rhythm was dictated by the mine whistle. A specific blast signaled the start of a shift, another the end. But there was a specific, terrifying signal—often a long, sustained blast—that meant an accident.

When that whistle blew, every woman in the camp would freeze. Children stopped playing. The silence that followed was suffocating until the news spread of whose husband or father had been hurt. These two children on the porch likely knew that fear. The boy’s thousand-yard stare might be the look of a child who has already learned that his father’s return home is never guaranteed. They are sitting on the porch, perhaps waiting for the shift to end, waiting to see the familiar silhouette of their father walking up that jagged path, black with soot but alive.

The Legacy of the Image

Why does this image matter today? It matters because it strips away the nostalgia often applied to American history. We like to think of the past in terms of triumph and progress, of a nation pulling itself up by its bootstraps. But these children had no boots. They had bare feet and a porch that was falling apart.

This photograph challenges the narrative of the “good old days.” For the families of Chaplin, West Virginia, the old days were hard, dirty, and short. They were days of exploitation where human life was tallied as a line item on a ledger, often less valuable than the mules used to haul the coal carts.

Furthermore, this image serves as a mirror to current struggles. The geography may have changed, and the industry may have shifted, but the dynamic of working poverty remains. The anxiety of the “gig economy,” the struggle to pay rent, the inability to afford healthcare—these are the modern echoes of the company town. The boy and girl on the porch are the ancestors of every child today who waits in a car while their parent works a second job, or who goes to school in worn-out clothes because the budget couldn’t stretch that far.

Conclusion: A Monument to Endurance

Ultimately, the power of this photograph lies in the resilience it captures. Despite the rotting wood, the choking dust, the hunger, and the fear, these children are there. They are enduring. The girl rubs her eyes, clearing her vision, refusing to be blinded. The boy sits, resting but ready to stand again.

They are the silent heroes of the industrial age. The coal their father mined made steel for skyscrapers, powered the locomotives that connected the coasts, and generated the electricity that lit the great cities of the North. The modern world was built on the backs of families like this one in Chaplin. They gave their lungs, their eyes, and their childhoods to fuel a prosperity they were rarely invited to share.

To look at them now, across the chasm of nearly a century, is an act of remembrance. We acknowledge their suffering, we validate their struggle, and we honor the sheer, gritty determination it took to simply sit on that porch and survive another day in the dust. They are not just victims of history; they are the bedrock of it.

News

GOOD NEWS FROM GREG GUTFELD: After Weeks of Silence, Greg Gutfeld Has Finally Returned With a Message That’s as Raw as It Is Powerful. Fox News Host Revealed That His Treatment Has Been Completed Successfully.

A JOURNEY OF SILENCE, STRUGGLE, AND A RETURN THAT SHOOK AMERICA For weeks, questions circled endlessly across social media, newsrooms,…

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own The year was 1883,…

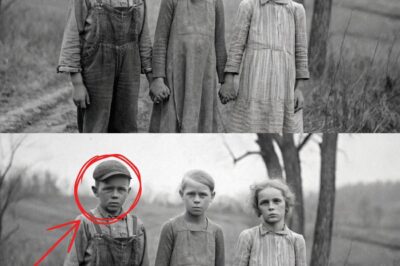

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist…

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart “Get your filthy hands…

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how.

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how. “Is this a joke?” barked…

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist….

End of content

No more pages to load