(Recife 1867) The Most Feared Slave Boy That Ever Lived: He Eliminated 19 People from the Same Family

Have you ever heard of a child who lost everything before even turning 10? A story that will chill you and make you question how far the thirst for revenge can take someone? Subscribe to the channel, share this video, and tell me in the comments where you’re watching from, because today I’m going to tell you the darkest story that ever happened in Recife.

Get ready to meet Zuri, the enslaved boy who became the nightmare of an entire family. My name is Zuri, I’m 14 years old now, but my story began when I was only nine. It was 1862. And the suffocating heat of March made the air in the sugarcane fields almost unbreathable. I worked at the Albuquerque house for as long as I can remember, along with my mother Kesi and my two younger siblings, Jengo and Amara.

The Albuquerque house was one of the most prosperous properties in Recife. Mr. Joaquim Albuquerque ruled everything with an iron fist, supported by his sons Antônio, Carlos, and Miguel, and his wife, Dona Esperança. They had other relatives living in the big house—uncles, cousins, brothers-in-law. In total, 19 people who considered themselves the owners of our lives.

On that fateful morning, I was carrying water from the well when I heard the screams. They weren’t ordinary screams of punishment; they were screams of despair, of those who know death is approaching. I dropped the buckets and ran towards the slave quarters, my heart pounding so hard it felt like it wanted to burst from my chest. What I saw marked me forever. My mother was on the floor bleeding. Mr. Antônio was holding a bloody knife while Mr.

Carlos laughed like a demon. Jengo, my 7-year-old brother, lay motionless beside her. Mara, only 5 years old, cried desperately, clinging to our mother’s dirty skirts. “Mom!” I yelled, running towards them. Mr. Miguel grabbed my arm with brutal force. “Quiet, brat. Your mother tried to steal food from the pantry.

Do you know what the punishment is for that?” “She didn’t steal anything!” I yelled, trying to break free. “Mara was sick. She just wanted some flour.” Mr. Carlos’s laughter echoed through the yard. “Sick. These animals don’t get sick. They pretend to avoid work.” It was then that I saw Mr. Antonio approach Amara.

The girl looked at me with those big, frightened eyes, extending her small hand towards me. “Zuri!” she whispered. The knife went down. Something inside me died at that moment. It wasn’t just my sister who died, it was any vestige of childhood that still existed within me. I felt a chill run down my spine, a darkness that would never leave me. “Now you,” said Mr.

Antônio, turning to me with the knife, still dripping blood. But Mr. Joaquim appeared at that moment. “No. This one here will live. He will carry the mark of what happens to those who disobey.” They dragged me to the center of the courtyard. All the other enslaved people were forced to watch. Mr. Miguel heated a red-hot iron in the fire while Mr. Carlos held me tightly. “

This mark will remind you and everyone else who’s in charge here,” said Mr. Joaquim, picking up the red-hot iron. The hot metal touched my forehead. The pain was indescribable, as if my skull were being split in two. The smell of my own burning flesh invaded my nostrils. But I didn’t scream, I didn’t cry, I just looked into each of their eyes, engraving their faces in my memory. “Look at him,” laughed Mr. Carlos. “

The kid doesn’t even cry, he must be a bit of an idiot.” They didn’t know that at that moment, while the iron burned my skin, I I was making a silent promise. A promise that would take five years to fulfill, but one that I would keep to the last detail. When they released me, I staggered to where my family’s bodies lay. Mr.

Joaquim ordered the other enslaved people to bury them behind the slave quarters in shallow graves like animals. “You’re going to work double now,” said Dona Esperança, approaching me. “You’re going to pay for what your mother did.” I looked at her in silence. She took a step back, uncomfortable with my gaze. That night, lying on the cold floor of the slave quarters, I touched the mark on my forehead.

My body was swollen and terribly painful, but the physical pain was nothing compared to what I felt inside. I closed my eyes and began to repeat the names like a prayer. Joaquim Albuquerque, Esperança Albuquerque, Antônio Albuquerque, Carlos Albuquerque, Miguel Albuquerque. There were five for now, but I knew there were more. Uncles, cousins, brothers-in-law, all who lived in that big house, all who benefited from our suffering.

I would get to know them one by one, study their habits, their weaknesses, their fears, and when the time came, they would pay. All of them. The other enslaved people began to avoid me after that day. They said there was something different about me, something that frightened them. Perhaps it was my constant silence or the way I looked at the big house every night before going to sleep.

Benedita, an older enslaved woman who cared for the children, tried to talk to me a few times. “Boy, you need to cry,” she would say. “You need to let the pain out, otherwise it will consume you from the inside.” But I couldn’t cry. The tears had dried along with my family’s blood. In their place, something cold and calculated had grown, something that gave me the strength to endure the endless days of forced labor and humiliation.

During the following months, I observed everything. I learned the schedules of each family member, their preferred routes through the property, where they slept, what they ate, who they spoke to. I discovered that Mr. Joaquim had a brother, Colonel Teodoro, who visited the house frequently, that Mrs. Esperança had two married sisters who lived on the property with their husbands and children. Nineteen people. I counted and recounted several times.

Nineteen people who had Albuquerque blood in their veins or who directly benefited from our enslavement. The mark on my forehead healed, leaving an R-shaped scar, for rebel, as they liked to say. But for me, that mark meant something else. It was a constant reminder of what I had lost and what I would do to honor my family’s memory.

The overseers began to fear me, though they wouldn’t openly admit it. There was something about the way I worked, in absolute silence, never complaining, never showing fatigue, that deeply disturbed them. “That boy isn’t normal,” I heard overseer João comment to overseer Manuel. “

He works like a machine, but never speaks, never smiles. It gives me the creeps.” They didn’t know that every lash I received, every humiliation I endured, only fueled the cold flame burning inside my chest. Every night I fell asleep repeating the 19 names, planning, waiting, because I knew that one day, when I was strong enough, when I knew enough, when the time was right, I would return to avenge every drop of spilled blood, and none of them would escape.

Two years have passed since that terrible day, and I have become a dark legend among the enslaved people of the Albuquerque household. They whispered my name in the sugarcane fields, always looking over their shoulders to make sure no overseer was listening. “Zuri, the boy who doesn’t cry,” they said. “Zuri who doesn’t feel pain,” but they were wrong. I felt pain, every imaginable pain.

The difference was that I had learned to transform it into something useful, into fuel for what was to come. It was 1864 now, and I was 11 years old. My body had grown, hardened by the hard work in the sugarcane fields. My hands were calloused, my muscles defined by constant effort, but it was my eyes that frightened people the most, eyes that seemed to carry an age far beyond my years.

That June morning, the heat was suffocating. The sun rose red over the sugarcane fields, promising another day of brutal work. I had been cutting cane since before dawn, my movements precise and mechanical, when I heard the familiar voice of overseer João. “Hey, brand mark!” he shouted, using the cruel nickname they had given me because of the scar on my forehead.

“Mr. Carlos, does he want to speak with you?” I dropped the machete and walked towards the big house, my bare feet making little noise on the red earth. The other enslaved people watched me pass, some with pity, others with a mixture of fear and admiration. Mr. Carlos was on the veranda drinking coffee and smoking a cigar.

At 25, he was considered the cruelest of Mr. Joaquim’s sons. He took pleasure in causing suffering. And I knew that any conversation with him wouldn’t end well for me. “Come closer,” he ordered without taking his eyes off the newspaper he was reading. I stopped a few meters away, maintaining my upright posture. I never lowered my head to them.

No matter how many times they beat me for it. “Do you know why I called you here?” he asked, finally looking at me. I remained silent. I had stopped speaking to any member of the Albuquerque family the day they killed my family. My voice was reserved only for the other enslaved people, and even then I spoke little. “Answer when I speak to you,” he He yelled, rising abruptly.

I remained silent, my eyes fixed on his. I saw something that gave me a dark satisfaction, a flash of unease, perhaps even fear. “You think you’re clever, don’t you?” he said, descending the steps from the porch. “You think your silence makes you special.” He stopped right in front of me, so close I could smell the alcohol on his breath.

I’m going to teach you a lesson about respect. The first punch hit my stomach hard enough to bend me in half, but I didn’t groan, I didn’t flinch, I just straightened up again and looked back into his eyes. “Impressive,” he murmured. “More for himself than for me. Let’s see how far this resistance of his goes.”

What followed was one of the most brutal beatings I had ever received. Mr. Carlos used his fists, then a whip, then a piece of wood. Each blow was calculated to cause maximum pain without killing me. After all, I was still valuable property. But throughout the beating, I didn’t utter a single sound. I didn’t cry, I didn’t beg, I didn’t scream, I just absorbed each blow, each humiliation, and added them to the bill that would one day be collected.

When he finally stopped, panting and sweating, I was still standing. My body was covered in wounds. Blood dripped from my nose and mouth, but my eyes remained firm, defiant. “What the hell are you?” he whispered, taking a step back. It was then that something extraordinary happened.

Other enslaved people began to gather around the veranda, drawn by the sounds of the beating. They saw me standing there, bleeding but not broken, and something changed in their eyes. Uncle Benedito, a 50-year-old man who had worked in the house since childhood, stepped forward. “Mr. Carlos,” he said, his voice trembling slightly. “The boy needs medical attention.” “He will survive,

” Carlos replied, but his voice no longer held the same confidence as before. “Excuse me, sir,” Uncle Benedito insisted. “But if he dies, Mr. Joaquim will not be pleased. The boy is one of our best workers.” It was true. Despite my age, I produced more than many adult men. My quiet determination made me tireless in the sugarcane fields. Mr.

Carlos looked around, noticing for the first time the crowd of enslaved people that had formed. They all looked at me with a mixture of reverence and astonishment. He realized that something had changed, that somehow his attempt to break me had had the opposite effect.

“Take him away from here,” he finally said, turning his back and climbing the steps to the veranda. Uncle Benedito and others helped me walk to the slave quarters. My legs trembled, but I refused to be carried. Each step was a declaration that I would not be broken. That night, while Aunt Benedita tended to my wounds, the other enslaved people gathered around me. It was rare to see so many people together in the slave quarters.

Usually, everyone was too exhausted to socialize after a day’s work. “How do you do it?” asked João, a 16-year-old boy. “How can you not cry, not scream?” I looked at him, then at the other faces surrounding me. They were faces marked by suffering, resignation, and fear. But at that moment there was something more. There was hope.

“The back,” my voice finally said, hoarse from lack of use during the day. “But the memory remains.” “Memory of what?” asked Maria, a young woman who worked in the big house. “Of injustice,” I replied, “of what they did to us, of what they continue to do.” Uncle Benedito approached, his old eyes shining with a light I hadn’t seen in a long time.

“You’re not like us,” he said softly. “There’s something different about you, boy. Something they fear.” He was right. I could see it in the overseers’ eyes, in the way Mr. Carlos had recoiled. They didn’t understand how a child could endure so much suffering without breaking, and that frightened them. In the following days, my reputation spread throughout the property.

The enslaved people began to seek me out when they needed courage, when they were about to give up. My silent presence became a symbol of resistance. “The boy who doesn’t cry is here,” they whispered to each other when the work became unbearable. “If he can endure it, so can we.”

But the overseers began to fear me openly. Overseer João avoided being alone with me in the sugarcane fields. Overseer Manuel always kept other enslaved people nearby when he needed to give me orders. “There’s something wrong with that boy.” I heard Overseer João say to Overseer Manuel one afternoon: “He’s not natural.

He works like a demon, never complains, never cries, gives me the creeps.” “He’s just a kid,” Manuel replied, but his voice didn’t sound convincing. “Kid, nothing. Did you see his eyes? It’s as if he’s always planning something.” They were more right than they imagined. Each passing day, I observed more, learned more, planned more. I discovered that Mr.

Joaquim had debt problems, that the property wasn’t as prosperous as it seemed. I learned that there were tensions between the Albuquerque brothers over the inheritance. More importantly, I discovered their routines, their weaknesses, their fears. Mr. Antônio was afraid of the dark and always slept with a lit candle. Mr.

Miguel drank too much and often staggered alone through the gardens at night. Mrs. Esperança took laudanum to sleep and would remain unconscious for hours. Each piece of information was carefully stored in my memory, like pieces of a puzzle that would one day fit together perfectly. One night, while I was looking at the large house illuminated by the windows, Uncle Benedito approached me.

“What are you thinking about, boy?” he asked. “Justice?” I replied without taking my eyes off the house. “What kind of justice?” I turned to him, and he recoiled slightly at the intensity in my gaze. “The only justice possible,” he said, “is that which comes from our own hands.”

That night I fell asleep repeating the 19 names, as I always did, but this time there was something different in my silent prayer. This time, I could feel that the time was drawing near. The boy who didn’t cry was growing up, and when the time came, they would discover that there were things far worse than tears. It was December 1865, and I had just turned 12.

The heat of the Pernambuco summer made the work in the sugarcane fields even more brutal, but I continued my relentless routine. Waking before dawn, working until nightfall, observing the big house, planning. On that fateful morning, something different was in the air. Mr.

Joaquim had arrived from the city the previous night with bad news about his debts. I could hear the heated arguments coming from Casagre, raised voices echoing through the property. “We need more production!” Mr. Joaquim shouted. “These damned slaves are getting lazy.” It was then that Mr. Miguel had an idea that would change everything. “Father?” He said, his voice carrying a cruelty I knew well. “

How about we set an example? Show everyone what happens to those who don’t produce enough?” I was working near Casagrande when I heard my name being shouted: “Zuri, branded one! Come here now!” I dropped my machete and walked towards the central courtyard, where the entire Albuquerque family was gathered.

Nineteen people looked at me with a mixture of hatred and morbid curiosity. My heart raced, but I kept my expression impassive. “This one here,” said Mr. Miguel, pointing at me, “is the perfect example of insubordination.” Three years have passed since we branded him, and yet, look at him.

He doesn’t lower his head, he shows no respect, Mr. Carlos Rio, that cruel laugh I knew so well. Perhaps the brand wasn’t enough. Perhaps we need something more permanent. They dragged me to the center of the courtyard, where there was a wooden structure used for public punishments. All the enslaved people were forced to stop working and watch.

I saw the fear in Uncle Benedito’s eyes, the anguish on Aunt Benedita’s face. “Fifty lashes,” announced Mr. Joaquim, “so that everyone can see what happens to those who defy this family.” They tied me to the structure, my back exposed to the scorching sun. Mr. Antônio picked up the whip, testing it in the air a few times. The sound of the leather cutting through the wind made some of the enslaved people recoil.

“Let’s see if you scream this time,” he said, positioning himself behind me. The first lash tore my skin like liquid fire. The second opened a deep cut. The third made me see stars, but I didn’t scream. I bit my tongue until I tasted the blood, but I didn’t give them the satisfaction of hearing me cry.

On the tenth lash, I heard Aunt Benedita sob. On the twentieth, some of the enslaved people began to pray softly. On the thirtieth, even some family members seemed uncomfortable, but Mr. Antônio continued. Forty lashes, forty-five, fifty. When They finally stopped; I could barely stay conscious. My vision was blurred. My body trembled uncontrollably.

Blood ran down my back, forming a pool on the ground. “Release him,” ordered Mr. Joaquim. When they cut the ropes, I collapsed to the ground like a sack of flour. But even so, even with the unbearable pain, I managed to lift my head and look at each of them. One by one, I etched their faces into my memory once more.

“Impressive,” murmured Colonel Teodoro, brother of Mr. Joaquim. “The boy really doesn’t cry.” “It’s as if he were made of stone,” said Dona Esperança. “But there was something in his voice that wasn’t admiration, it was fear. They left me there on the courtyard floor as a warning to the others. It was Uncle Benedito who carried me back to the slave quarters, his tears dripping onto my face as he whispered prayers.

For three days I hovered between life and death. Aunt Benedita cared for me with herbs and prayers, cleaning my wounds with warm water and applying poultices of medicinal leaves. Other enslaved people took turns at my side, whispering words of encouragement. “Don’t give up, boy,” said João. “You are our hope.

You are stronger than all of them together,” murmured Maria. But during those three days of delirium, something changed within me. The physical pain was nothing compared to the mental clarity it brought.” I realized I would never be strong enough to confront them directly. Not while I was just an enslaved boy on an isolated property. I needed time.

I needed to grow, to learn, to prepare. I needed to disappear. On the fourth night, when everyone was asleep, I rose silently. My body still ached terribly, but my determination was stronger than the pain. I gathered a few things: a small machete I had hidden, a piece of cloth, some edible roots that Aunt Benedita had taught me to identify.

Before leaving, I knelt where my family was buried. I placed my hand in the red earth. And I made a silent promise. Wait for me, I whispered. I will return, and when I return, they will all pay. Then, like a shadow, I slipped out of the slave quarters and made my way into the woods surrounding the property. The forest was dense and dark, full of dangers I knew only from the stories of the elders.

There were jaguars, venomous snakes, quilombola people who didn’t trust strangers, but none of that scared me more than the prospect of continuing to live under the yoke of the Albuquerques. The first days in the forest were the hardest of my life. My wounds were still open, attracting flies and other insects.

Hunger was constant, and I had to be careful not to eat anything poisonous. At night, the cold of the mountains made me tremble uncontrollably, but I survived. I learned to build shelters with branches and leaves, to find clean water by following the sound of streams, and to identify edible fruits and roots.

I learned to move silently through the forest, to hide when I heard the voices of fugitive slave hunters. Weeks passed. My body adapted to the wilderness, becoming thinner but also more resilient. My senses sharpened. I could hear a branch breaking hundreds of meters away, smell campfire smoke even before seeing it.

It was during my second week in the woods that I found the quilombo. I was following a stream looking for fish when I heard voices. Instinctively, I hid behind a large tree and watched. Three Black men, clearly formerly enslaved, were filling gourds with water. “The slave hunters are looking for someone,” one of them said. “A boy from the Albuquerque house, they say he disappeared two weeks ago. How old is he?” asked the other. “

Twelve years old. He has an R-shaped mark on his forehead. The Albuquerques are offering a good reward for him.” “If I were that boy,” said the third, “I would be far away from here. The Albuquerques don’t forgive.” They left, but their words lingered in my mind. I knew I couldn’t approach the quilombo.

They might hand me over for the reward or simply not trust me. I needed to continue alone. Months passed. Summer gave way to autumn, then winter. I became a legend in the forest. The hunters spoke of a ghost that stole food from their traps and left strange footprints near the streams.

Some said they had seen a small, dark figure moving among the trees, but when they approached, they found nothing. Throughout all this time, I never stopped thinking about the Albuquerque house. Every night, before sleeping, I repeated the 19 names. I planned how I would return. How would I get my revenge? How would I make each of them pay for what they had done to my family? The forest taught me things that no slave quarters could teach.

I learned to be patient like a jaguar waiting for its prey. I learned to be silent like a snake approaching a rat. I learned to be ruthless like nature itself. When winter ended and spring began to awaken the forest, I knew I was ready for the next phase of my plan. I wouldn’t return yet, it was too soon, but I would begin to approach the property, to observe, to prepare.

One night I climbed a tall tree on the edge of the woods and looked towards the Albuquerque house. The lights of the large house shone in the distance, and I could see the shadows of people moving behind the windows. “They’re all still there,” I murmured to myself. All 19. A cold smile formed on my lips.

The first smile I’d given in almost a year. “Wait for me,” I whispered to the night. “The boy who doesn’t cry is growing up, and when he returns, you’ll discover there are things far worse than tears.” The night wind carried my words toward the big house, like a foreshadowing of what was to come.

It was 1867, and two years had passed since my escape into the woods. I was fourteen now, but I looked much older. The wild life had shaped my body and mind in ways the Albuquerques could never have imagined. I was taller, stronger, and infinitely more dangerous. During those two years, I observed the Albuquerque house from afar, like a predator studying its prey.

I learned their new routines, discovered their growing weaknesses, and realized something that filled me with a dark satisfaction. They were destroying themselves from within. The property was no longer the same. Mr. Joaquim’s debts had piled up, and the family was divided by internal disputes.

Some enslaved people had escaped, others had died of disease, and the sugarcane production had drastically decreased. But most importantly, they had forgotten about me. That March night, I approached the property closer than I had in months. I moved like a shadow among the trees, my bare feet making no sound on the damp earth.

The moon was new, and the darkness was my ally. I stopped at the edge of the woods, observing the main house. Some windows were lit, and I could hear raised voices coming from inside. A familiar argument, judging by the sound. It was then that I saw something that made my blood boil. Mr. Carlos was in the garden, drunk, abusing a young enslaved woman.

She was crying softly, begging him to stop, but he only laughed. My hand instinctively closed around the handle of the machete, which I had sharpened until it was razor-sharp. Would it be that easy? A quick, silent movement, and Mr. Carlos would be the first to pay. But no, it wasn’t time yet. My revenge would be complete or it would be nothing. I retreated into the woods, but not before leaving a small gift.

The next morning, Mr. Carlos found a dead rabbit hanging from the tree under which he had committed his violence. The animal was clean, without visible injuries, but clearly dead. Tied to the rabbit’s neck was a small piece of cloth, a piece of the clothing I was wearing the day my family was murdered. “

What the hell is this?” he shouted, waking the whole house. Mr. Joaquim went down to investigate, followed by the other family members. They gathered around the tree, looking at the dead rabbit with a mixture of confusion and unease. “It must be some enslaved person trying to scare us,” said Mr. Miguel, but his voice didn’t sound convincing.

“Dead rabbit?” asked Dona Esperança. “That doesn’t make sense.” It was Uncle Benedito who recognized the piece of cloth. I saw him approach the group, his old eyes widening when he saw the familiar fabric. “Sir Joaquim,” he said, his voice trembling. “I’ve seen this cloth before.” “Where?” asked Mr. Joaquim

abruptly. “It belonged to the boy Zuri, sir, the one who ran away two years ago.” A heavy silence fell over the group. I could see, even from afar, the tension that settled between them. “Impossible,” said Mr. Carlos, but his voice had lost its confidence. “That boy has been dead for a long time. The forest devoured him.”

“Maybe not,” murmured Colonel Teodoro. “Maybe he survived.” “So what? If he survived. Mr. Miguel exploded. He’s just a boy, what can he do against us?” But I could see that the seed of doubt had been planted. During the following days, I continued my psychological campaign. I left barefoot footprints in the mud near the Big House.

I made small noises during the night, breaking branches, throwing stones against the windows. Always small, subtle things that could be explained as coincidence. But when added together, they created an atmosphere of paranoia. A week later, I left my second gift. A dead cat on the Big House’s porch, with the same kind of cloth tied around its neck.

This time, there was something more. Small cuts on the animal’s body made with surgical precision. They weren’t fatal wounds, but they were clearly intentional. “This is no coincidence,” said Dona Esperança, her voice sharp with nervousness. “Someone is doing this on purpose.” “But who?” asked Mr. Antônio.

“And why?” It was then that Aunt Benedita, who was cleaning the porch, whispered something that made everyone fall silent. The boy who doesn’t cry has returned. From that moment on, paranoia completely took hold in the Albuquerque House. They started locking the doors during the day, something they had never done before.

They hired more thugs to patrol the property. Some family members started sleeping with guns beside their beds, but I knew every inch of that property better than they did. I had spent years observing, learning, planning. I knew where every floorboard creaked, which window had a broken lock, where the guard dogs slept. My third gift was the most audacious.

I entered the main house itself during the night and left a dead rat on Mr. Carlos’s pillow. He woke up from the smell and screamed so loudly he woke the whole house. “He was here!” he yelled, running through the hallways in panic. “He was in my room.” “Who?” asked Mr. Joaquim, but everyone knew the answer.

“The boy Zuri, he’s alive and he’s hunting us. Don’t be ridiculous,” said Mr. Miguel, “but I could see the fear in his eyes. How could a boy get in here unseen?” But they knew it was possible. They remembered the quiet boy, who never cried, who endured any punishment without breaking.

They remembered the eyes that seemed to see through their souls. During the following weeks, the Albuquerque family began to disintegrate. The arguments became more frequent and violent. Some family members wanted to hire more security, others wanted to flee to the city. Some even suggested selling the property.

“You’re all crazy,” shouted Mr. Joaquim during one of these arguments. “You’re afraid of a boy.” “He’s not a boy anymore,” said Colonel Teodoro grimly. “Those were years in the woods. If he survived, we don’t know what he became. They were right to be afraid. During my time in the woods, I had become something they couldn’t comprehend. I

was no longer the frightened boy who had run away two years before. I was a patient, calculating, relentless predator. I learned from the animals of the forest. The patience of the jaguar that can wait hours for the perfect prey. The precision of the snake that attacks only when it is sure of success. The persistence of the wolf that follows its prey until it can no longer run. My fourth gift was a clear message.

I left 19 small wooden crosses planted in the garden of the Casagrande, each with a name engraved on it. The names of all the members of the Albuquerque family. When they discovered the crosses the next morning, there was total panic. ‘He knows!’ cried Dona Esperança. ‘He knows how many of us there are.’ ‘How can he know?’ asked Senr. Antônio, his voice trembling. ‘

Because he observed us?’ said Colonel Teodoro. ‘For two years he observed us and planned. It was then that…’” Mr. Joaquim made a desperate decision. “Let’s hunt him down,” he announced. “Let’s gather all the men on the property and scour every inch of the woods until we find him.” “And if we don’t find him?” asked Mr. Miguel. “We will find him,” said Mr.

Joaquim with forced determination. “He’s just a boy. No matter what he’s learned in the woods, he’s still just a boy.” But while they planned their hunt, I was already planning my response. They wanted to hunt me. Perfect. I would let them come, because in the woods I was the predator and they were just lost prey in unknown territory.

That night, I looked at the big house one last time before retreating into the depths of the forest. The lights flickered in the windows like candles at a wake. “Come,” I whispered to the darkness. “Come find me in the woods! Let’s see who hunts whom.” The night wind carried my words like an omen of death. The hunt was about to begin, but they didn’t know that they had been prey for a long time.

The hunt began one April morning, when the sun was still struggling to pierce the dense fog that covered the sugarcane fields. Mr. Joaquim had gathered 15 men—overseers, henchmen, and some enslaved people forced to participate. All were armed with machetes, rifles, and hunting dogs.

I watched them from a tall tree, my body as still as a stone statue. Two years in the woods had taught me to blend into the forest, to become invisible, even when I was in plain sight. They passed within 10 meters of me, their dogs barking and sniffing, but they couldn’t detect me. “Spread out,” ordered Mr. Joaquim. He couldn’t have gone very far. “He’s just a boy,” how wrong they were.

“I followed the main group for hours, moving silently through the treetops. I watched as they grew tired, frustrated, and began to argue amongst themselves. The forest was my territory now. And they were clumsy invaders. It was late afternoon that I decided to act. Mr.

Carlos had separated from the main group, following what he thought was a promising trail. He was alone, sweaty and irritated, when he stopped to drink water from a stream. It was the perfect moment. Descending from the tree like a silent shadow, my feet touching the ground without making a sound. Mr. Carlos had his back to me, kneeling on the bank of the stream.

For a moment, I just watched him. The man who had laughed while killing my little sister. “Looking for someone?” I asked softly. He turned abruptly, dropping his water canteen. His eyes widened when he saw me. No longer the skinny boy of two years ago, but a tall, muscular young man, with eyes that seemed to carry the darkness of the forest itself.

“Zuri,” he He whispered, his voice trembling. “Mr. Carlos,” I replied, my voice calm, like the surface of a lake before a storm. “How long has it been?” He tried to grab the shotgun he had left on the ground, but I was faster. One fluid movement and the weapon was out of his reach. “What do you want?” he asked, backing away slowly. “Justice,” I replied simply.

“Look, boy,” he said, trying to sound authoritative, but failing miserably. “If you surrender now, I promise you will be treated with mercy. Can we forget all this?” And a cold sound echoed through the woods, like the call of a raven. “Forget?” I repeated. “How can I forget the sound of your laughter when you killed Mara? How can I forget the way you held the knife?” His face paled. “That was, that was a long time ago. It was different then.

So, for you, maybe. For me, it was yesterday.” I drew the machete I had sharpened until it was razor-sharp. The blade gleamed in the filtered light of the woods, and Mr. Carlos took another step back. “Please,” he pleaded. “I have a family, I have children.” “I did too,” I replied.

Do you remember them? He tried to run, but the woods were my home now. I knew every root, every branch, every stone. He stumbled and fell, scraping his face on the thorns. When I reached him, he was on the ground, looking at me with pure terror. “Do you know what marked me most that day?” I asked, kneeling beside him.

It wasn’t the pain of the mark on my forehead, it wasn’t the screams of my family, it was his laughter. “I… I’m sorry,” he stammered. “No,” I said, raising my machete. “But will he feel it? What happened next was quick and precise. Two years in the woods had taught me how to hunt, how to kill cleanly and efficiently. Mr. Carlos died as he had lived, in fear.

When I finished, I wiped the blade of the machete on his clothes and stood up. I felt a strange peace, as if a weight I had carried for years had finally been removed. One, 18 remained. I left the body where it was and walked away silently. The other hunters would find him eventually and then they would know that the hunt had become something very different from what they imagined. Two hours later, I heard the screams.

We found him! Overseer João shouted, his voice echoing through the woods. Mr. Carlos, my God, Mr. Carlos. I watched from afar as they gathered around the body. Some vomited, others recoiled in horror. Mr. Joaquim stood still for long minutes, looking at his dead son with an expression of utter shock.

“How?” he murmured. “How could a boy do this?” “He’s no longer a boy,” Colonel Teodoro said, his voice grim. “Look at the cuts. This was done by someone who knows exactly what they’re doing.” They carried the body back to the big house, the abandoned hunt. I followed them through the shadows, watching as the news spread across the property.

The enslaved whispered amongst themselves, some with fear, others with something that sounded like hope. “The boy who doesn’t cry has returned, I heard Aunt Benedita say, and he brought justice with him.” That night, the Albuquerque house was under siege. All doors and windows were locked. Guards were posted at every entrance. The family gathered in the main room, their altered voices echoing through the house.

“We have to get out of here,” Dona Esperança said, pacing nervously around the room. “Do we have to go to town and abandon everything?” asked Mr. Miguel. “This property is our life.” “What life?” Mr. Antônio exploded. “My brother is dead.” Killed by a boy who should be rotting in the woods.

“He’s not a boy anymore,” Colonel Teodoro repeated. “Years alone in the woods, that changes a person, transforms them into something different.” Mr. Joaquim remained silent for a long time, looking at the makeshift coffin where his son lay. “Let’s hire more men,” he finally said. “Soldiers, professional hunters, let’s surround this woods and burn every tree if necessary.” “And if that doesn’t work?” asked one of the sisters-in-law.

“It will work,” said Mr. Joaquim, but his voice lacked conviction. While they planned, I moved through the property like a ghost. I knew every secret passage, every blind spot, every moment when the guards relaxed their vigilance. The house that had once been my prison was now my hunting ground. On the second night after Mr.

Carlos’s death, I made my next move. Mr. Miguel had a habit of drinking alone in his office late into the night. It was a routine I had observed for months. That night, when he was sufficiently drunk, I silently entered through the back window. He had his back to me, looking at a family portrait on the wall.

In the portrait, everyone was smiling, happy, unaware that one day a marked boy would return to collect his debts. “Beautiful memories,” I said softly. He turned, staggering, almost dropping the bottle of cachaça. “You?” he whispered, his eyes glazed with alcohol and fear. “I confirmed it by closing the window behind me.

The guards,” he began, “are sleeping. The alcohol you offered them had a little extra. Herbs you learned to use in the woods.” His face paled as he understood the implication. “You poisoned my men? I only made them sleep. I’m not like you. I don’t kill innocents.” He tried to scream, but I was faster. One hand over his mouth, the other holding the machete against his throat. “Silence,” I whispered. “

We don’t want to wake the family. It’s not their time yet.” His eyes widened in terror when he understood that I had a plan, not just blind revenge, but something far more calculated. “Do you remember the day they branded my forehead?” I asked, keeping my voice low. “You were holding the red-hot iron.” He tried to speak, but my hand still covered his mouth. “

You said I was half an idiot because I didn’t cry, but you were wrong. I didn’t cry because I was planning. Even at 9 years old, I was planning this moment.” I removed my hand from his mouth, but kept the machete in place. “Please,” he whispered. “I can give you money, freedom, anything you want. I want justice. And justice can’t be bought.” “This isn’t justice,” he said desperately.

This is murder, just like what you did to my family. He had no answer for it. What happened next was even faster than with Mr. Carlos. Mr. Miguel died silently, his eyes losing their shine as he stared at the family portrait on the wall. Two. Seventeen remained.

I left the body in the chair, positioned as if he had fallen asleep drunk. It would be hours before someone discovered he was dead. Before leaving, I wrote a message on the wall with his blood. Seventeen remain. As I climbed out the window, I heard a noise coming from the hallway. Someone was awake. I quickly hid in the shadows of the garden and watched.

It was Mrs. Hope, pacing nervously through the hallways with a candle in her hand. She seemed unable to sleep, probably tormented by nightmares about what had happened to Mr. Carlos. She passed the office door, hesitated, then continued walking. It would only be a matter of time before she discovered the body. But I would already be far away by then, back in the safety of the woods, planning my next move. As I walked away from the big house, I heard a scream echo through the night.

Dona Esperança had found the body. “Miguel! Miguel!” She screamed, “Someone, come quickly!” Soon, the whole house was awake, raised voices echoing through the property. Lights came on in all the windows, and I could hear the sound of people running through the hallways. From the top of a tree, on the edge of the woods, I observed the chaos I had created.

The Albuquerque house was in total panic now, two family members dead in two days. The message on the wall made it clear that this was only the beginning. 17 remain, I murmured to myself, repeating the words I had written on the wall. The night wind carried my voice through the property, like a whisper of death promising more blood to come.

The revenge had officially begun, and I discovered it tasted like justice. The next few days were filled with absolute terror at the Albuquerque house. After finding two bodies and the sinister message on the wall, the family fell into utter despair. They hired more guards, locked all the entrances, and some members even tried to flee to the city, but I was always watching, always waiting.

It was as if the house itself had become my web and they were trapped flies, waiting to be devoured one by one. On the third night it was Mr. Antonio’s turn, the man who had held the knife that killed my mother and my brothers. He slept with a pistol under his pillow and a candle always lit, but his fear of the dark was greater than his courage.

I entered through the attic, silently descending the wooden beams until I reached his room. He was awake, staring intently at the door, the pistol trembling in his sweaty hands. “I know you’re there,” he whispered into the darkness. “I can feel you, can I really?” I asked, my voice coming from behind him. He turned sharply, but I was already beside the bed. One swift movement and the pistol was on the floor.

“How did you get in?” he asked, his voice breaking with fear. “The same way you entered our slave quarters that night, uninvited.” His eyes widened as he understood that I remembered every detail of that terrible day. “You held the knife?” “I did.” “My voice, calm as death.

You thrust it into my mother’s chest as she begged for her children’s lives. I was obeying orders,” he mumbled. “And I am obeying justice.” Three. Sixteen remained. From that moment on, the house became an asylum. The family members refused to be alone. They all slept together in the main room, with armed guards at each door. But this only delayed the inevitable.

Colonel Teodoro was next, the brother of Mr. Joaquim, who always supported the family’s cruel decisions. I caught him as he tried to flee to the city in the middle of the night, thinking he could escape through the back road. “You can’t escape justice,” I told him as he lay dying.

“It always finds a way.” Four. There were 15. Dona Esperança was the fifth, the woman who had ordered me to work double shifts to pay for what my mother had done. She died in her own room, surrounded by all the riches she had accumulated with the blood and sweat of the enslaved. “Your jewels cannot buy forgiveness,” were the last words she heard. Five.

Fourteen remained. With each death I left a new message. Fourteen remain, thirteen remain, twelve remain. The words written in blood on the walls became a countdown to the Albuquerque family’s apocalypse. Mr. Joaquim tried to hire a private army, but the men fled when they discovered who they were fighting against.

Stories about the ghost boy spread throughout Recife. They said I could walk through walls, that I was immune to bullets, that I had made a pact with the devil. The truth was simpler and more terrible. I was just a young man who had learned to be patient, silent, and ruthless. The cousins, brothers-in-law, uncles, they all fell one by one.

Some tried to fight, others tried to flee, some even tried to beg for mercy. But for each of them, I had a specific memory of cruelty, a particular reason. “You laughed when they marked me,” he told his cousin Eduardo before killing him. “You spat in the food they gave us,” he told his brother-in-law Roberto. “You whipped children for fun,” he told his uncle Sebastião.

“Each death was a page turned in the book of my pain. Each name crossed off the list was a step closer to the peace I had sought since that terrible day. When only five family members remained, something changed. Mr. Joaquim, who had become a shadow of the authoritarian man he once was, made a desperate decision. “

We will surrender,” he announced to the survivors. “We will offer everything we have, the property, the money, everything.” “Do you think he will accept?” asked his daughter-in-law Maria Albuquerque. “He has to accept. We are all that remains.” But they didn’t understand that this was never about money or property.

It was about justice. It was about honoring the memory of a mother who died protecting her children, of a 7-year-old boy who never had a chance to grow up, of a 5-year-old girl who died calling my name. On the 15th night I entered the room where the five survivors were gathered.

They huddled in the center of the room, trembling like leaves in the wind. “Zi,” said Senr. Joaquim, his voice broken. “Can we talk?” “Now? You want to talk?” I asked, walking slowly around them. “Where was that willingness to talk when my family was begging for their lives?” “We made mistakes,” he admitted, “but this can stop here.

You can have everything: the property, the freedom, enough money to live like a king.” “I don’t want to be a king,” I replied. “I want justice.” “This isn’t justice!” Maria Albuquerque shouted. “This is massacre. Like what you did to hundreds of enslaved families over the years?” She had no answer. “Fifteen people from my family died on this property,” I continued. “

Not just my mother and siblings, my grandfather who died of exhaustion in the sugarcane fields. My grandmother who died of illness because you refused to give her medicine. My uncles, cousins, all who carried my blood and died under your whip.” Mr. Joaquim paled when he understood the extent of my pain. “Fifteen lives,” I repeated. “And you are nineteen. I’m still being generous.” What happened next was quick and final.

One by one, the last members of the Albuquerque family paid for their crimes. Mr. Joaquim was the last, and before he died, he… He whispered, “May God have mercy on your soul.” “God already has,” I replied. “He gave me the strength to do what was necessary.”

When I finished, I was alone in the silent room, surrounded by the bodies of those who had destroyed my family. Nineteen people, nineteen names crossed off my list. I walked to the window and looked at the sugarcane fields where I had worked as a slave. The sun was rising, painting the sky red like the blood that had been spilled. It is done, I whispered to the wind. Mother, jengo amara, it is done.

For the first time in eight years, I felt tears streaming down my face. They were not tears of pain, but of relief. Justice had been served. My family could finally rest in peace. I left Casagre for the last time, leaving behind the bodies and the memories.

The enslaved people of the property met me in the courtyard, their eyes filled with a mixture of fear and wonder. What happened? Uncle Benedito asked. Justice, I replied simply. And now? Aunt Benedita asked. I looked at them, people who had suffered as much as I had, who had lost as much as I had, but who had never had the opportunity to seek revenge.

“Now you are free,” he said. “The Albuquerque family no longer exists. This property has no owners anymore.” Some wept, others fell to their knees in gratitude. Some simply remained silent, trying to process what had happened. “And you?” Uncle Benedito asked. “What will you do now?” I looked towards the woods.

My home for so many years. “I will disappear,” I said. “Like a ghost that has fulfilled its mission.” And that is exactly what I did. Three months had passed since the night the Albuquerque family was completely eliminated. The property had become a ghost town, abandoned by the enslaved who had fled in search of a better life, avoided by the locals who whispered stories about the ghost boy who had brought bloody justice to Recife. I watched everything from afar, from the safety of the woods that had

become my true home. The big house was empty now, its windows broken. Letting in the wind that whistled through the corridors, where once echoed cries of pain and cruel laughter. The authorities came, of course, investigated, asked questions, searched for clues.

But what could they find? 19 bodies and a story no one wanted to believe. The story of an enslaved boy who had become the personification of vengeance. That July morning, I was sitting in the same tree from which I had watched the property for so many years when I heard familiar voices. Uncle Benedito and Aunt Benedita had returned, accompanied by some other former slaves from the property.

I descended silently and approached them. When they saw me, some instinctively recoiled, but Uncle Benedito stepped forward. “Zuri!” he said, his voice heavy with emotion. “We thought you had disappeared forever.” “Almost,” I replied, “but I wanted to say goodbye.” “Say goodbye?” Aunt Benedita asked, “Where are you going?” I looked towards the horizon, where the sun was beginning to set over the abandoned sugarcane fields, far away, to a place where no one knows my name or my story. “But you are a hero,” said João, “The young man who once

asked me how I could not cry. You freed us. You freed us all.” I didn’t answer by shaking my head. “I am not a hero. I am just someone who collected a debt.” “A debt that needed to be collected,” said Uncle Benedito firmly. “How many families did they destroy? How many children died under their whips? You did what none of us had the courage to do.”

“And now?” I asked. “What will you do?” “Some of us will try to find relatives in other cities,” said Aunt Benedita. “Others will stay here, working on neighboring properties as free men.” “And are you sure you want to leave?” “I am,” I answered without hesitation. “My mission here is fulfilled.

My family can rest in peace, but I need to find a way to live with what I did.” “Don’t you regret it?” asked Maria, the woman who worked in the big house. I thought for a long moment before answering: “I don’t regret doing justice,” I finally said, “but I regret becoming the kind of person capable of doing what I did.

Revenge has a price, and that price is part of your soul.” They were silent, processing my words. “Where did you learn so much wisdom?” Uncle Benedito asked. In the woods, I replied, nature teaches that everything has consequences, that every action generates a reaction, that life and death are just parts of the same cycle.

We walked together to the place where my family was buried. The simple graves had been marked with small wooden crosses that someone had made. Probably Aunt Benedita. I knelt before the graves and placed my hand in the red earth. Mother! I whispered, Jengo, Amara, it’s done. They all paid. You can rest now.

The wind blew softly, making the leaves of the trees whisper like distant voices. For a moment, I felt as if they were there with me, finally at peace. I stood up and turned to the others. “Take care of this place,” I said, “don’t let history be forgotten. Don’t let other children go through what I went through.” “We promise,” Uncle Benedito said solemnly.

“What if someone asks about you?” João asked. “Tell them that the boy who doesn’t cry finally found his tears,” I replied, “and that they washed away all the pain.” I hugged each of them. People who had been my family when I had no one else. People who had given me strength when I thought I had none left.

When the sun had completely set, I began walking towards the road that led away from Recife. I didn’t look back. There was nothing left to see. I walked all night, my bare feet making little noise on the beaten earth. At dawn, I arrived in a small town where no one knew me. There I found work as a carpenter, using the skills I had learned in the woods to work with wood.

I adopted a new name, Samuel. A simple, common name that didn’t attract attention. I let my hair grow to hide the scar on my forehead. I learned to smile again, to talk to people, to live like a normal person. But at night, when I was alone, I still heard the whispers. Stories arrived from Recife about the ghost boy who had wiped out an entire family of slave owners.

Stories that grew and transformed with each repetition, until I became a legend. Some said I was a vengeful spirit still haunting the sugarcane fields. Others claimed I was a demon sent to punish the cruel. There were those who swore they had seen me in the shadows, watching other properties where enslaved people were mistreated.

The truth was simpler. I was just a man trying to live with the choices I had made. A man who had discovered that revenge, however justified, left scars on the soul that never fully healed. Years passed. I married a kind woman who never asked about my past.

We had children, two boys and a girl. I gave them the names my brothers could never bear, Jengo and Amara. I taught my children about justice, but also about mercy, about the importance of fighting injustice, but also about the danger of letting anger consume the soul. Father, my daughter once asked me, “Why do you sometimes get sad when you look at the sunset?” Because I remember people I loved who are no longer here, I replied, “Are they in heaven?” “Yes,” I said, embracing her. “And they are at peace.” When I grew old, stories about

the ghost boy still circulated in Pernambuco. Parents told their children about the enslaved boy who had become the personification of justice. Cruel slave owners looked over their shoulders, fearing that their own victims might one day return to collect their debts.

And perhaps that was true justice, not just the vengeance I had carried out, but the fear it had planted in the hearts of those who oppressed the weak. On my deathbed, surrounded by my children and grandchildren, I felt a peace I hadn’t experienced since childhood. I had lived a good life after those dark years. I had loved and been loved.

I had built instead of just destroying. “Grandpa,” whispered my youngest grandson. “Tell us a story.” I smiled, remembering all the stories I could tell—stories of pain and revenge, of justice and redemption, of a boy who had lost everything and found a way to move on. “

Once upon a time,” I began, my voice weak but firm, “there was a boy who learned that true strength comes not from the ability to inflict pain, but from the ability to overcome it.” And as I told my story, an edited version, appropriate for young ears, I felt as if I were finally closing the last chapter of a book I had begun to write on that terrible day, so many years ago.

When I died, in the early hours of a quiet day, the last words I whispered were the names I had carried in my heart all my life. Kes, Jengo, Amara. I’m going home. And in Recife, where it all began, the night wind still whispered through the abandoned sugarcane fields, carrying stories of a time when justice had the face of a child and the heart of a ghost.

The boy who doesn’t cry had finally found his peace, and his legend would live on forever. Reminding everyone that some debts, no matter how much time passes, will always be collected. This was the story of Zuri, the enslaved boy who became a dark legend in Pernambuco. A story about justice, revenge, and the price we pay for the choices we make. If you’ve made it this far, leave a comment about what you thought of this narrative.

Subscribe to the channel for more stories that will give you chills and share with anyone you think needs to know this legend. Until the next story.

News

GOOD NEWS FROM GREG GUTFELD: After Weeks of Silence, Greg Gutfeld Has Finally Returned With a Message That’s as Raw as It Is Powerful. Fox News Host Revealed That His Treatment Has Been Completed Successfully.

A JOURNEY OF SILENCE, STRUGGLE, AND A RETURN THAT SHOOK AMERICA For weeks, questions circled endlessly across social media, newsrooms,…

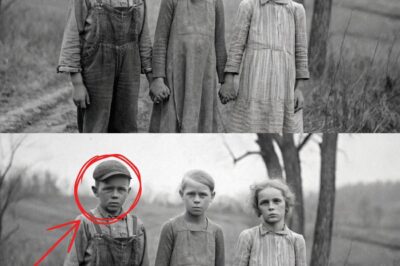

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own The year was 1883,…

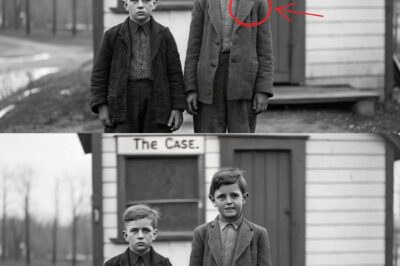

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist…

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart “Get your filthy hands…

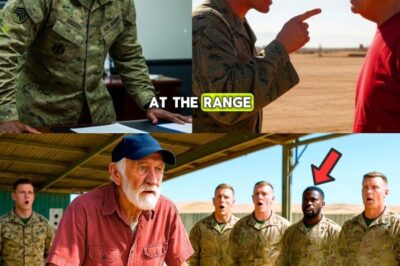

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how.

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how. “Is this a joke?” barked…

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist….

End of content

No more pages to load