Master Gave His Daughter to the Slaves — What She Became Broke Them All

They said the master’s daughter wasn’t right in the head, that she smiled at things no one else could see, and cried when the wind changed. After her mother died, the house grew quiet, too quiet, until the day the master walked down to the slave quarters with the little girl by the hand. He said he couldn’t raise her alone, that the women down there knew how to tend to broken things, and so he left her with them, his own child, barefoot, trembling, staring up at faces that had buried too many children of their own. But what they didn’t know was that the little girl had already learned how love worked in that house, and what she became among them broke them all.

Before we begin, make sure you subscribe to the Macabb Record. Hit the bell so you never miss another story that history tried to hide. Now, let’s go back to Mississippi, 1846.

The house fell silent the week the mistress died. No crying, no praying, just the sound of wind moving through the long hallways, brushing against curtains that hadn’t been drawn in days. The master ordered the mirrors covered, and the clock stopped, as if time itself had been put to rest beside her. They buried her on the hill behind the house where the magnolia trees leaned over the graves like tired old women. The slaves weren’t allowed near the ceremony. They stood at the edge of the field instead, heads bowed, watching as the little girl, Laya, clutched her father’s coat and stared at the coffin lowering into the ground.

She was only eight, small for her age, and spoke with a soft lisp that made her words sound like humming. She didn’t cry that day. She just watched, eyes vacant as if she didn’t understand what death meant yet. Or maybe she did and simply couldn’t say it. After the funeral, the master locked himself in his study. He stayed there for 3 days, refusing food, whiskey, or company. When he finally emerged, he looked thinner, unshaven, eyes sunken. He didn’t call for his daughter. He didn’t even look at her.

The housekeeper, a tall woman named Essie, said the girl had been wandering the halls at night, carrying her mother’s comb and singing to herself. “She keeps looking for the misses,” Essie whispered to the others, “talking to her reflection like it’s still her.” Laya’s presence began to disturb the house staff. She would sit in corners for hours, tearing at the hem of her dress, whispering to herself in a language no one could understand. Sometimes she laughed suddenly for no reason. Other times she screamed when touched like she’d been burned. The master didn’t notice or pretended not to. His grief turned to resentment. The sight of her, her mother’s eyes, her mother’s hair was too much for him.

One evening, after supper, he called for two of the men and told them to fetch the women from the quarters. The next morning, as the sun rose over the fields, the slaves saw him coming down the hill. His daughter walked beside him barefoot, clutching a small doll with one arm missing. She looked afraid but curious too. The men followed a few paces behind, silent. When they reached the quarters, the master stopped. He said the girl would be staying there, that he had work to do and she needed proper company. No one spoke. The women just stared at the small figure standing in the dirt, her hair tangled, her lips trembling. Then he turned and walked back to the house, leaving her there, his only child, among the people who had buried their own children by his hand. And for a long time no one moved.

The first night no one slept. The little girl sat on a stool by the hearth, her bare feet tucked under her dress, watching the fire as if it might speak to her. The women whispered from their beds, unsure what to do. They’d been given no instructions, only the order that she would stay among them now. Old Mabel, the midwife, finally rose. Her back was bent from years of lifting other people’s burdens. She knelt beside the girl, offering her a small wooden cup of milk. “Here now, baby,” she said softly. “You drink this, you’ll sleep easy.”

Laya didn’t move. Her eyes stayed fixed on the flames. Then she turned slowly, her voice barely above a whisper. “Papa says fire eats people when they lie.”

Mabel froze. The women looked at one another across the room. “No, child,” Mabel said after a moment, forcing a smile. “Fire keeps folks warm. That’s all it do.” But Laya didn’t answer. She lifted the cup to her lips and drank, eyes never leaving the fire.

Later, when the women thought she was asleep, they began to talk in low voices. “Why’d he bring her here?” one asked. “She got a bed up at the house.”

“Cuz she don’t fit nowhere,” Mabel muttered. “She too much like her mama, but not enough to be kept.”

Essie’s niece, Ruth, young and quick tonged, whispered. “She looks simple to me. Like she ain’t all there.”

Mabel hushed her with a look. “Don’t you call no child simple. God makes all his creatures the way he sees fit. Ain’t her fault she born to the wrong kind of people.”

From the corner, Laya stirred. Her doll fell to the floor, landing face down. She began to hum a tune, soft and strange, the kind a mother might sing to a baby if she’d forgotten the words long ago. The sound filled the room, fragile, offkey, but tender. The women went quiet. Even the crickets outside seemed to stop their song. When the girl finished, she looked at them with a faint smile and said, “Mama used to sing that when papa got mad.”

Nobody spoke. That night, Ruth woke to a noise, a small voice whispering near her bed. She turned and saw Laya standing beside her, holding the one-armed doll. “Papa said, ‘Bad girls get sent here,’” she murmured. “He said, you know how to fix them.” Ruth couldn’t find her words. She just stared. Laya leaned closer, her breath shallow, her eyes wide and unblinking. “Can you fix me?” Then she walked back to the corner and curled up on the dirt floor, the doll pressed against her chest.

By morning, everyone in the quarters understood one thing. The child they’d been given wasn’t evil, but she carried something in her, something that had been broken before she ever learned how to speak.

By the second week, the girl had found her rhythm in the quarters. She followed the women through their daily routines, fetching water, peeling potatoes, feeding the infants that clung to their mother’s hips. She didn’t speak much, but she watched everything, always watching. She liked to sit by the washing tubs, splashing her hands in the soapy water. Sometimes she’d hum while Ruth scrubbed the clothes, and Ruth would catch herself humming along before she realized what she was doing. It was easy to forget who the child was when her hair caught the morning light or when she smiled without thinking, but there were moments that unsettled them.

When the overseer passed through the yard, Laya’s shoulders would stiffen. Her eyes would go dull, and she’d lower her head just like the others, not out of imitation, but instinct. And once, when he shouted at one of the men, Laya whispered something under her breath. Mabel heard her and froze. “What you say, child?”

Laya blinked. “Papa says you beat them till they listen.”

The words were spoken so plainly that Mabel’s stomach turned. “Don’t you talk like that,” she said firmly. “Ain’t right to say such things.”

But the girl just tilted her head. “Papa says it’s right if it makes them quiet.”

That night when Mabel told the others, no one laughed. Ruth crossed herself, whispering, “Lord, she ain’t supposed to know them words.”

Over the next days, small habits appeared. Laya began to point when she wanted something instead of asking. She snapped her fingers at the younger children, told them to move quick, the same way she’d once heard her father bark at the servants. When the others corrected her, she’d frown and mumble. “But Papa said that’s how good folks talk.” The women didn’t scold her. They knew she didn’t mean harm. But every gesture, every phrase carried the echo of her father’s cruelty, softened only by her innocent confusion. Still, there were moments that broke their hearts.

One morning, Ruth found Laya sitting outside, holding her doll upside down by the arm, whispering to it, “Don’t cry, mama. Papa said, ‘Don’t cry.’”

Ruth knelt beside her. “Who you talking to, sugar?”

Laya looked up, eyes wide. “Mama’s inside this one.” She lifted the doll gently, pressing its ragged face against her cheek. “She said she ain’t gone nowhere. She just got small.”

Ruth smiled weakly, brushing dirt from the child’s hair. “Then you keep her safe here.”

Laya nodded. “I will. But papa said, ‘Small things get lost.’”

That night, as the candles burned low, Mabel whispered to Ruth, “She don’t know what she is. Not his, not ours. That kind of lost don’t mend easy.”

Outside the crickets sang again. But beneath their hum, another sound drifted through the quarters. A small uneven tune, the child’s voice rising and falling like a memory trying to find its way home.

Weeks passed and the little girl became part of the rhythm of the quarters. The women began to care for her the way they once cared for their own, those who’d been sold, those buried in unmarked dirt behind the fields. They brushed her tangled hair, taught her to knead bread, even let her nap beside the babies in the shade. It wasn’t pity that bound them to her. It was recognition. Something about the way she looked at the world, curious, broken, never quite understanding why people hurt each other, felt too familiar.

Mabel took to calling her little Missy. She said the name softened the sting of what she was. Even Ruth, who’d first feared her, started to smile when the child tugged her sleeve or offered a wild flower from the creek. “Ain’t her fault she’d come from him,” Ruth said one afternoon. “She just got born in the wrong story.”

Still, strange things lingered. Laya laughed at pain, sometimes even her own. Once she tripped while carrying a basket of corn and scraped her knees bloody. When Ruth rushed to help, the girl only giggled, staring at the blood with quiet fascination. “It’s red like mama’s dress,” she said. And when the overseer’s whip cracked in the distance, she didn’t flinch like the others. She tilted her head, listening, then whispered, “Papa says, ‘That sound means everyone’s being good again.’”

Mabel told her gently, “That sound don’t mean good, child. That sound means sorrow.” But Laya only looked confused, as if the words didn’t fit together right.

That night, as the rain came, Mabel found her sitting by the window, tracing patterns in the fog on the glass. “What you drawing, baby?” she asked.

Laya smiled faintly. “A house with no doors?”

“Why no doors?”

“So papa can’t find me?”

Mabel’s heart broke a little more. The next morning, the master came down to the quarters for the first time since leaving her there. His boots sank into the wet earth. The women stiffened, hands frozen mid task. He called for Mabel. “How’s the girl?” he asked. His tone was clipped as though he were asking after a sick animal.

Mabel’s hands twisted in her apron. “She eats, she sleeps. The others look after her best we can.”

“Good,” he said. “Keep her clean. Teach her to work. She can shell peas, carry water. She’ll learn.” Then his eyes shifted, cold and sharp. “Don’t let her forget who she is.” He turned to leave, and that was when Laya came running out from behind the hut, barefoot and muddy. She stopped short when she saw him. “Papa,” she whispered.

He didn’t bend, didn’t smile. He only said, “Mind what they tell you, girl?” and walked away.

Laya stood in the rain until he was gone. Then she looked up at Mabel and said, “Papa talks to God like that, too.” Mabel couldn’t answer because in that moment she realized the child wasn’t only repeating him, she was becoming him.

The days grew longer and heavier. The air hung thick with heat and silence, and the rhythm of work dulled everything into habit. The women moved like clock hands, their bodies knowing what to do, even when their minds drifted elsewhere. And in the middle of it all was Laya, barefoot, humming, following them like a shadow that had forgotten its master. She had learned quickly, too quickly. She mimicked the way the older women folded rags, the way they hushed crying babies, the way they bowed their heads when the overseer passed. But what unsettled them most wasn’t what she copied. It was what she remembered.

Sometimes she’d stand in the doorway of the cabin, her voice flat, reciting words that had never belonged in a child’s mouth. “Papa says, ‘If you don’t cry, the hurt don’t count.’” Or, “Mama said Papa’s love was heavy. That’s why she sank.”

Mabel told the others, “That child ain’t simple. She just full of echoes.”

One evening, when the sun was bleeding red across the field, Ruth caught Laya scolding one of the smaller children. The boy had spilled a bucket of water, and Laya’s little hand came down hard across his cheek. The sound was sharp, out of place in the hush of the evening. “Don’t you spill it again,” she said, her voice steady, too calm. “Papa says bad ones get fixed that way.”

Ruth grabbed her wrist before she could strike again. “Laya,” she hissed. “We don’t hurt nobody here.” The girl froze. For a moment, confusion flickered in her eyes. Then tears welled up and she began to cry. Not the sobbing of a frightened child, but the dry, trembling sound of someone who didn’t know why they were sorry.

Ruth knelt, holding her close. “He ain’t here, baby. You don’t got to be him.”

That night, Laya sat outside alone. She didn’t eat, didn’t speak. The fireflies blinked around her, tiny lights rising from the grass like lost spirits. When Mabel went to check on her, she found the child whispering to her doll again. “I did what Papa said,” she murmured. “Now I’m bad, too.”

Mabel crouched down beside her. “No, honey. You ain’t bad. You just don’t know different yet.”

The girl looked up, her face streaked with tears. “Then who going to teach me different?” Mabel didn’t answer. She couldn’t.

The next day, the women noticed small things. Laya started rearranging their tools, giving orders to the younger ones. She repeated phrases she’d heard her father use. “Do it proper. Don’t talk back. You’re mine when I say you’re mine.” It wasn’t mockery. It was mimicry. The way children learn to walk or to pray, except what she’d learned to imitate wasn’t love or faith. It was power. And though she was only a child, her voice carried the weight of the man who’d broken them all.

By midsummer, Laya had become a fixture of the quarters, not just a presence, but a shadow that followed every task and echoed every word. She was too young to understand cruelty, yet too practiced at imitating it. Some mornings she would rise before the women, moving through the small cabin, touching their faces lightly as they slept, whispering words only she could understand. Other times she’d sit outside in the dirt, scratching circles into the ground with a stick, murmuring, “Work hard. Be still. Don’t look up.”

At first, the women tried to correct her gently. They thought they could unteach what she’d learned. Replace her father’s poison with something softer. Lullabies, small kindnesses, bits of laughter that drifted up like prayers between chores. But there were moments when their love couldn’t reach her.

One afternoon, while the women shelled peas under the trees, Laya began to sort them herself, muttering to her doll, “Good ones stay, bad ones go.” She flicked the darker peas into the dust. When Mabel told her to stop, Laya looked up, her face blank. “Papa says bad ones spoil the rest.”

Mabel took her by the shoulders. “You don’t listen to what that man say no more. You hear me?”

The girl stared at her, confused, then frightened. Her lip trembled. “Then who do I listen to?” No one could answer.

That night a storm rolled in, shaking the quarters. Rain pounded the roof like fists and thunder rattled the floorboards. Most of the women huddled together, whispering hymns. But Laya sat alone by the door, rocking back and forth, whispering to the doll she’d named Mama. When the lightning flashed, her face glowed white against the dark, eyes wide and distant. She wasn’t praying. She was listening for something only she could hear.

Later, when the storm quieted, Ruth found her still sitting there. The doll was gone. “What you do with her?” Ruth asked.

Laya looked up. “She didn’t sing right.”

“What you mean?”

“She kept saying Papa’s name when I told her not to.”

Ruth’s stomach turned. She reached out to touch her, but the girl flinched hard, curling into herself. “Don’t hit me,” she cried. “Papa said, ‘That’s how you make it stop.’”

Ruth froze, her hand hovering in the air. “I ain’t him, Laya,” she said softly. “I ain’t going to hurt you.” But the child didn’t answer. She just rocked, whispering, “Bad ones get fixed.”

Outside, the storm had passed, but the air still carried its weight. Mabel stood in the doorway, watching the girl in the flicker of the dying fire light. “She’s learning what she seen,” she said quietly. “We all do. Problem is, she seen too much.” No one slept that night because for the first time they weren’t sure if the child needed saving or if she’d already become what she feared most.

The master didn’t come down again until the cotton bloomed. By then the air was heavy with the smell of rain and rot, and the child he’d left among the slaves no longer looked like the one he’d brought. Her hair hung wild, her skin browned from the sun, and her feet were calloused from running barefoot in the dirt. When he appeared at the edge of the quarters, the women stopped what they were doing. Tools fell silent. Conversations died. Even the cicadas seemed to hush.

He looked around, expression hard, calculating. His eyes fell on Laya, who was crouched near the fence, humming softly to a pile of sticks she’d arranged in neat rows. “What’s she doing?” he asked Mabel.

Mabel hesitated. “She’s uh… playing, sir. She builds things, keeps her quiet.”

He took a step closer. “Looks to me like she’s making graves.”

Laya turned then, smiling faintly when she saw him. “Papa,” she said, her voice calm, almost practiced. “You come to see my house?”

He frowned. “What house?”

She pointed to the sticks. “This one. It’s where good ones go when they stop crying.”

The master blinked. “Who told you that?”

“You did,” she said it plainly, like a fact she couldn’t unlearn. For a moment, his jaw tightened and something behind his eyes flickered. Guilt, maybe, or disgust.

He turned to Mabel. “You teach her that?”

Mabel’s voice cracked. “No, sir. Ain’t nobody teach her nothing like that.”

He stared at them all as though waiting for one of them to confess. Then he looked back at the girl who had gone back to her work, patting the dirt gently around each tiny grave. “Get her washed,” he said coldly. “She’s coming back to the house.”

“I’ve had enough of this foolishness,” Mabel started to protest. “Sir, she…”

But his glare cut her short. “She’s my blood. I’ll not have her living like one of you.” He turned and started back toward the main house, boots crushing the flowers along the path.

When he was gone, Laya looked up, her small brow furrowed. “Did I make him mad again?”

Ruth knelt beside her. “No, baby. You didn’t do nothing wrong.”

“Yes, I did.” Laya’s voice broke, trembling with something that sounded more like shame than fear. “Papa says, ‘Bad ones make him tired.’ I make him tired.” She pressed her dirty hands together as if in prayer. “Maybe if I stop talking, he won’t see me.”

That night she refused supper. She sat by the doorway again, humming her mother’s broken song. The sound of it carried through the quarters like smoke, soft, cracked, and full of something no one could name. And when Mabel looked at her from her cot, she thought, “The Lord help her. He took her away to make her proper again, but he don’t know. He’s the one she learned it all from.”

The day the master came for her, the quarters fell quiet as a church before dawn. The men stopped chopping wood. The women froze midwash. Even the children, those who’d grown used to the small joys that came between grief, stood still. He came on horseback this time, dressed sharp and polished, as if appearances could undo the rot that had settled in the house. Two of the overseers followed behind him, though they didn’t look her way. They knew the story of the girl, and like everyone else, they didn’t speak it aloud.

Laya was sitting by the steps, humming softly to herself, the hem of her dress damp with morning dew. When she saw the horse, she smiled faintly. “Papa,” she said, as though she’d been expecting him all along.

He dismounted slowly. “Come here, girl.”

She hesitated, glancing toward Mabel. The old woman gave a small nod, though her throat was too tight to speak. Laya rose, brushing dirt from her dress, and walked toward him barefoot. When he reached down to lift her onto the horse, she flinched, just a small twitch, but enough that his hand froze midair. His expression darkened, the shame behind his eyes twisting into something meaner. “Don’t act scared,” he said. “Ain’t no reason to be.”

He lifted her up and swung into the saddle behind her. The women watched in silence as they rode up the hill, the child’s small figure pressed against his coat, her face turned toward the wind.

That night, the house was lit again for the first time in months. Candles glowed behind the tall windows, and music drifted faintly through the trees. The old piano, offkey, but desperate, filling the silence she’d left behind. From the quarters, the women listened. Mabel murmured a prayer. Ruth said nothing. She just stared at the lights and whispered, “He took her back to kill what’s left of her.”

Inside the house, the girl sat at the dining table, her hands folded neatly like her mother’s once had been. The master poured himself whiskey after whiskey, his jaw tight. “You’ve been living like them long enough,” he said finally. “You’ll eat proper now. Speak proper. No more foolishness.”

She nodded, her eyes downcast. “Yes, sir.” But as she spoke, her voice shifted, low, cold, mimicking his, the same tone he used when giving orders.

He froze, glass halfway to his lips. “What did you say?”

She blinked, confused. “I said yes, sir.” But it wasn’t confusion. It was repetition. He realized then she was giving his words back to him exactly as he’d given them to others. For the first time, he saw himself sitting there, not in the mirror, but across from him, in the body of a small, broken girl who didn’t understand she was only acting out the world he’d built.

He turned away, his hand shaking as he refilled his glass. “Go to bed,” he muttered. “You talk too much.”

She rose obediently and left the room. But before she disappeared down the hall, she whispered, “Papa talks too much, too.” The sound of her small feet faded, leaving him alone with the echo.

Days after Laya’s return, the house began to breathe again, but not like it once had. Its rhythm was strange now, uneasy, as though the walls themselves knew something had gone wrong. The servants spoke in whispers. The master moved through the rooms like a ghost, too proud to admit he’d died already. Laya followed him everywhere. She sat on the floor beside his chair when he read, repeated his words under her breath, copied the way he crossed his legs, the way he rubbed his thumb against the rim of his glass before taking a drink. Sometimes she even sat at his desk when he left the room, arranging his papers just so, pretending to sign her name the way he did, though she couldn’t write a single word.

At first, he found it harmless. He even laughed once, a hollow sound that startled the housekeeper. “She’s learning,” he said, “taken after her daddy.” But that laughter didn’t last.

One evening when supper was served, she sat across from him, hands folded, waiting for him to speak first. When he began blessing the food, she bowed her head too. But when he finished, she didn’t raise it. She stayed bowed, lips moving silently.

“What are you muttering, girl?” he asked.

She looked up, her eyes calm. “I said what you said to Mama before she died.”

The words hit him like a hand across the face. He stared at her, pale and still. “And what was that?”

She hesitated, tilting her head like she was searching for the right sound. “You made me love you wrong.”

The fork slipped from his hand. “Who told you that?” he said sharply. “Who said that to you?”

“Mama did,” she answered. “But her mouth didn’t move.”

He slammed his glass down. “Enough. You hear me? Enough of this nonsense.”

She flinched, shrinking back. “I didn’t mean bad,” but something had already shifted inside him. He saw her not as his child anymore, but as the living proof of his shame, his wife’s eyes, his own cruelty, and all the things he couldn’t control staring back at him from that small, trembling body.

The next morning, he made her stand before the mirror in her mother’s old room. “Look at yourself,” he said. “You ain’t one of them. You’re mine. You’ll remember that.”

She nodded faintly, staring at the reflection as though she didn’t recognize the girl looking back. Then she whispered, “She looks like you when you get mad.”

He raised his hand, but stopped himself. The room went still. For the first time, he realized he wasn’t looking at his daughter anymore. He was looking at the mirror image of the man he’d taught her to be. He turned away, his voice shaking. “Go on,” he said. “Get out of my sight.” She did as she was told, but before leaving she pressed her small hand to the mirror, leaving a print in the dust that looked just like his.

After that morning by the mirror, the house seemed to fold in on itself. The child, who once hummed through the halls, now moved without a sound. Her small feet left no trace on the floorboards. She no longer asked questions or spoke her father’s name. She became like the dust that clung to the curtains, there but unseen, waiting for a breeze that never came.

At first, the master told himself this was good. Obedience was peace. Quiet meant healing. But the silence had a weight to it that unsettled him. He would wake at night to find her standing in the doorway, watching him sleep, her head tilted, her expression unreadable. “What are you doing there, girl?” he’d bark.

Her voice came soft, almost kind, “Waiting for you to stop shouting in your sleep.” He said nothing after that, but his dreams grew worse.

Each morning, she’d be sitting at the kitchen table, staring into her cup of milk, lips barely moving. When asked what she was whispering, she’d answer, “Saying sorry, cuz Papa forgot how.” He began keeping her busy with chores, sweeping, folding linens, polishing the piano keys her mother once played. But even then, she found ways to haunt him. Once he caught her arranging the silver spoons in pairs, murmuring, “Mama says folks shouldn’t die alone.”

He snatched the spoons away. “Don’t talk about your mother.”

She didn’t flinch. “Then what should I talk about?” He had no answer.

The housekeeper, Essie, tried to help. She brought the girl food, small kindnesses, bits of songs she remembered from her own childhood. But Laya didn’t eat much anymore. She’d only say, “Mama’s singing now. She don’t need me to.”

The master’s guilt turned sour. He began mistaking pity for defiance, grief for insolence. Each time he looked at her, he saw the woman he couldn’t control. The same eyes, the same quiet, and he hated her for it. One afternoon, when he found her staring into the parlor mirror again, he snapped. “You think she’s in there?” he shouted. “You think she’s watching?”

Laya blinked slow and tired. “She ain’t watching.” She waited.

He grabbed her by the shoulders, shaking her hard enough to make her teeth clatter. “Stop talking like her. Stop talking like that.”

Her voice came out small, almost a whisper. “I’m trying, Papa. But your voice don’t leave.”

He let go so suddenly she stumbled backward, hitting the piano. The strings inside gave a faint broken note, one that hung in the air long after the room went still. He turned away, breathing hard, his hands trembling. “Go upstairs,” he said hoarsely, “before I forget you’re my blood.” She did quietly, without crying.

Later that night, he found the piano lid open. On the keys sat a line of dust, perfectly straight, except for one small handprint pressed into the center. Hers. And beside it, carved faintly into the wood with something sharp, were the words, “I’m still listening.”

Words spread slow from the big house, carried down to the quarters like a sickness moving through the air. Nobody said it out loud, but everyone knew something wasn’t right up there. The lights burned late, later than they ever had before, and sometimes in the quiet after midnight, the wind carried sounds that didn’t belong to the living: the crack of a belt, the slam of a door, a man’s voice rising and breaking, and the soft, muffled hum of a child who no longer cried.

Mabel was the first to hear it clear. She’d stepped outside one night to pour out her wash water when she saw the faint glow in the upstairs window, one candle still burning. And though she couldn’t see much, she could hear the rhythm of something heavy striking wood again and again. She pressed a hand to her mouth, whispering, “Lord, don’t let that be her.”

By morning, Laya had bruises on her arms. The housekeeper said she’d fallen, but no one believed that. When the field hands came up to deliver corn, Ruth caught a glimpse of the girl through the kitchen window. She was sitting at the table folding napkins with the careful precision of someone who had been taught that stillness was safety. Her lip was split. Her eyes were blank.

That night, Mabel gathered the others in her cabin. “She’s up there dying slow,” she said. “And ain’t no one coming to save her.”

Ruth’s hands were shaking. “What we supposed to do? He’s the master. You go near that house, you don’t come back.”

“Maybe,” Mabel said. “But I can’t sit here listening to that child forget how to be human.”

The next night, they waited until the fields were quiet. Mabel and Ruth crept toward the big house, barefoot, keeping to the shadows. The smell of whiskey floated from the open parlor window. Inside, the master sat slumped in his chair, his shirt undone, his hand gripping a half empty bottle. Laya was kneeling on the floor beside him, picking up shards of glass from where he dropped his drink. He watched her the way a man watches his own reflection, disgusted, but unable to turn away.

“You’re going to keep pretending you can’t understand me,” he slurred. She didn’t answer. He leaned forward, his voice low and sharp. “You hear me?”

Finally, she looked up. “I hear you always,” she said softly. “Even when you ain’t talking.”

Something in that answer broke him. He slammed the bottle against the wall, the sound echoing through the house. “You ain’t her,” he shouted. “You’ll never be her.”

Laya didn’t move. She just whispered. “I know. You made sure.”

Mabel clutched Ruth’s arm, pulling her back from the window. “We can’t stay,” she hissed. “He’ll see us.” But as they turned to leave, Mabel heard the faintest sound drift from the room. A single piano key pressed in the dark, trembling under a child’s hand.

After that night, something in the master broke for good. He stopped speaking to the servants, stopped working the books, stopped leaving the house altogether. He spent his days moving from room to room like a man wandering through the wreckage of his own life and his nights with a bottle in his hand and a voice that didn’t sound like his anymore.

Only Laya stayed close to him, not out of love, not out of fear. It was something quieter, something the women in the quarters would have called duty, born of loneliness. She rose when he rose, shadowed his steps, repeated his movements as if the two of them were bound together by the same tired soul. If he slammed a door, she did too. If he drank from a glass, she’d pour herself water and lift it in the same slow motion, lips trembling with the effort of matching him. Sometimes when he’d drift into sleep at his desk, she’d stand behind him, eyes wide and distant, whispering, “You don’t got to shout anymore, Papa. I hear you just fine.” He’d wake with a start, looking around the room as though her voice had come from the walls.

By August, the servants began avoiding the house altogether. They said it smelled wrong inside, like whiskey and candle wax, and something sweet turning sour, and every night they swore they heard faint music, one hand playing slow, uneven notes on the piano upstairs.

Mabel begged the housekeeper, Essie, to intervene. “You go up there, tell him that child needs someone else to tend her,” she said. “He’ll listen to you.”

Essie shook her head. “He don’t listen to no one no more. That house is his grave now. Hers, too, if she stays.” But by then, it was already too late.

One evening, the master sat in his wife’s old room with a candle burning low. The mirror she used to comb her hair before church still hung above the vanity, warped with age. He was drunk again, his eyes red, his hands unsteady. Behind him, Laya stood barefoot, silent. He looked at her reflection instead of her face. “Why you looking at me like that?” he said quietly. “Ain’t you tired of me yet?”

She didn’t answer. Her small fingers twisted the hem of her dress. He gave a bitter laugh. “You’re the only thing left that looks at me.” He turned toward her, reaching out to touch her cheek, but she stepped back. His hand froze midair. “You afraid of me?”

Her eyes didn’t move. “You told me to be.”

For a long time, neither of them spoke. The candle sputtered, shadows trembling across the wall. Then she said softly, “When you hurt me, I sound like you. When I’m quiet, I sound like mama. I don’t know which one to be.”

The glass of whiskey slipped from his fingers. It hit the floor and rolled under the vanity, spilling amber into the cracks, and for the first time the master began to cry. Not loud, not broken, but the way a man cries when he knows he’s already been judged.

For days after that night, no one saw the master in the fields or by the porch. The curtain stayed drawn. The smoke from the chimney grew thin, and the sound of the piano, that soft, broken melody played by a single trembling hand, was the only proof there was still life inside the Brantham house.

Mabel heard it first one morning while hanging laundry near the treeline. It wasn’t a tune she recognized. It came in stops and starts, uneven, like someone trying to remember a song that used to mean something. She stood there, hands dripping with water, staring at the house. “That child’s still breathing up there,” she whispered. “But I don’t know if she’s living.”

By noon, Ruth came running from the kitchen yard. “Essie say the master ain’t eaten,” she said. “Ain’t slept neither. Just sits at that piano watching her like he waiting for her to stop.”

Mabel looked toward the hill, jaw tight. “He’s killing her slow. Just don’t know it yet.”

That night, Mabel lit a lantern and walked to the edge of the field. Ruth followed, though fear made her steps uneven. “We can’t,” Ruth said. “You go up there. He’ll shoot you dead.”

“He can try,” Mabel muttered. “But somebody’s got to bring that girl back down to the world.”

They waited until the house lights dimmed, then crept through the tall grass, the scent of wet magnolia clinging to their skirts. The door was unlocked. It always was now. The air inside was thick with the smell of whiskey, sweat, and something faintly metallic like old pennies. The parlor was in disarray. Furniture overturned, glass scattered, candles burned to stubs. And in the middle of it all, Laya sat at the piano. Her small hands hovered over the keys, moving without sound. Her dress was torn at the shoulder. Her eyes were open, but distant, unfocused.

Mabel rushed to her. “Laya. Baby, it’s me.”

The girl blinked like someone waking from a deep sleep. “Mabel.” Her voice was soft, uncertain. “I’ve been waiting for you.”

“Come on now,” Mabel said gently. “We going home.”

But before she could lift her, a low voice came from the doorway. “She is home.”

The master stood there half in shadow, his shirt unbuttoned, a pistol hanging loosely at his side. His face was drawn and hollow, but his eyes, those eyes were sharp again. “She don’t belong down there no more,” he said. “She’s mine. Always been mine.”

Mabel turned, defiant, even through the fear. “She don’t belong to nobody no more. You done made sure of that.”

His jaw clenched. The pistol didn’t rise, but his hand trembled. “You think you can take her from me?”

Behind them, Laya spoke quietly. “You don’t have to take me.”

Both of them turned. She was standing now, her hands flat against the piano lid, her voice calm and strange. “I already gone.”

The room went still. The wind outside pressed against the shutters, the candle light trembling like it too was afraid. Mabel’s breath caught. Ruth’s hands twisted around the lantern handle until her knuckles went white. The master stood frozen in the doorway, his pistol hanging loose, the gleam of the metal catching the flicker of light. Laya stood by the piano, bare feet in the dust, her head tilted the way her mother’s once had when she listened to sermons she didn’t believe in.

“I already gone,” she said again, her voice calm but not hollow, like she was describing a truth that no one else could see.

The master’s throat worked. “Don’t talk, foolish girl.” He took a step forward. She didn’t move. “You hear me?” His tone sharpened. “You ain’t gone nowhere.”

Her gaze flicked toward Mabel and Ruth, then back to him. “I ain’t here either.”

He faltered, eyes narrowing as if trying to understand, then his voice cracked, low and ragged. “I gave you everything I had left. You don’t get to walk away from me.”

Mabel stepped in front of Laya, shielding her with her body. “You didn’t give her nothing but your ghosts.”

“Move aside,” he barked.

“No,” Mabel said, steady as a grave marker. “You done enough.”

For a moment, nobody breathed. The master’s hand twitched, the pistol rising just an inch, but his aim wavered. He looked from the old woman’s face to the girl behind her, small, fragile, still as a reflection. Then Laya stepped out from behind Mabel and stood before him.

“You can hit me,” she said softly. “That’s what you do when you love someone, right?”

He froze. “Who told you that?”

“You did,” she said. “Every time you cried after.”

Her words cut deeper than any bullet could. His arm dropped. He looked at her, really looked at her for the first time since her mother’s death. The face, the voice, the quiet defiance. It was all her mother’s, yet ruined by him. His lips trembled. “I didn’t mean to.”

She took one step closer, her eyes glassy, but sure. “I know. That’s why it hurt worse.”

The pistol slipped from his hand. It hit the floor, discharging with a thunderclap that tore through the room. Smoke filled the air. The women screamed. When it cleared, the master was still standing, staring down at his daughter, who hadn’t moved. The bullet had struck the piano instead, splintering the wood and leaving one single trembling note hanging in the air.

Laya didn’t flinch. She just looked at him, expression unreadable. “See,” she whispered. “You can’t kill what you already broke.”

The master fell to his knees, the sound of his sobbing low and desperate. “God forgive me,” he muttered again and again. But no one answered him. Outside the magnolia shivered in the wind. Inside the child stood over the wrecked piano, her fingers trailing across the splintered keys, pressing one, two, three notes, each softer than the last. And for the first time, she smiled. Not cruelly, not sweetly, just as if she finally understood how silence was made.

The echo of that gunshot hung in the air long after the smoke had cleared. It clung to the rafters, to the drapes, to the breaths no one dared take. When it finally faded, the only sound left was the rain, slow, steady, seeping through the broken shutters as though the sky itself was mourning. The master stayed on his knees, the pistol lay at his feet, useless now, his hands shaking as if the weight of it still clung to him.

Mabel moved first. She crossed the room, her voice trembling, but steady enough to be heard. “Come on, child,” she whispered. “You done here?”

Laya didn’t resist. She looked at her father once, not with hate, not with love, but with the strange hollow calm of someone who’d finally run out of fear. Then she turned away and followed Mabel toward the door. Ruth held the lantern, her arm shaking so hard the light jumped and trembled across the walls behind them.

The master called out, “Laya!” She stopped but didn’t turn. “I didn’t mean for it to be like this.”

The girl’s voice was barely a whisper. “You never do.”

And then she was gone. The women led her through the rain, down the hill, past the magnolia trees, and back toward the cabins. The mud sucked at their feet, heavy and cold. When they reached the quarters, no one spoke. The others gathered at the doorways, faces pale in the lamplight, watching as Mabel wrapped the girl in a blanket and sat her by the fire.

Laya didn’t cry. She just stared into the flames, her reflection dancing across her eyes. “Can I stay here now?” she asked.

Mabel brushed damp hair from her forehead. “You can stay as long as you need, baby.”

The girl nodded small and slow. “He said I belong to him.”

Mabel’s voice cracked. “You don’t belong to nobody no more.”

Later that night, when the others had drifted to uneasy sleep, Ruth found Mabel sitting outside, staring at the hill. The house stood in the distance, a faint light flickering in an upstairs window. “You think he’ll come after her?” Ruth asked.

Mabel shook her head. “No, he’d done seen himself. That’s worse than death for a man like him.”

And she was right. The next day, no one saw the master in the fields. The following morning, the smoke from his chimney stopped rising altogether. Some said he’d locked himself in the study. Others whispered that he’d gone down to the river where his wife was buried and never come back.

Laya stayed quiet for days. She slept by the fire, holding the one-armed doll tight against her chest. When she did speak, it was only to say, “Papa’s house, don’t sound no more.” No one corrected her because in truth it didn’t. The house on the hill had fallen silent, and silence was all he had left to give her.

Summer slid into autumn, and the Brantham plantation began to rot from the inside out. The cotton field still bloomed, the river still moved, the crows still circled the hill, but the life of the place had drained away like blood soaking into dirt. The big house no longer sent down orders. The master’s shutters stayed closed. No lamps burned past dusk. At first, the overseer tried to keep the work moving, barking at the men, demanding quotas, pretending the world hadn’t shifted. But the slaves knew the truth. The master’s silence had turned the land hollow. There was no command, no direction, just echoes.

And at the center of those echoes was Laya. She lived among them now, sharing their meals, sleeping on the floor beside Mabel’s cot, speaking only when spoken to. The women treated her gently, like a child who’d been left too long in the cold. Ruth sewed her a new dress from scraps of muslin, white and plain. “She looked almost like an angel now,” Ruth said, trying to smile.

Mabel’s answer was quiet. “Angels ain’t born from pain, child. They just visit it.”

At night, the girl still hummed to herself, soft and tuneless. Sometimes she whispered to her doll again, but the words had changed. “Don’t cry, Mama,” she’d murmur. “He can’t reach no more.”

One evening, when the moon was full and the air thick with the smell of drying leaves, Mabel heard her speaking to someone who wasn’t there. The sound came from outside near the magnolia tree behind the cabins. She followed it through the dark until she found Laya kneeling by the roots, her hands pressed into the mud.

“What you doing out here, baby?” Laya turned, eyes calm and bright in the moonlight. “I’m listening.”

“Listening to what?”

“To him,” she said. “He don’t shout no more. He just talks quiet now.”

Mabel’s heart seized. “Ain’t nothing up there, child. Ain’t no one left to talk.”

But Laya smiled faintly. “Then who say my name when I sleep?”

Mabel took her hand and led her back inside, refusing to answer. She told herself it was just a dream the child couldn’t shake, that the ghosts of cruelty cling hardest to those who didn’t deserve them. But later, when the fire burned low, she heard the girl hum again, a slow, dragging tune, and beneath it, so faint it might have been the wind, a man’s whispering voice following each note.

The next morning, the air over the hill looked strange. No smoke, no movement, but a white film of mist clung to the house, thick and still as milk. Laya stood at the doorway of the quarters, staring up at it. “He ain’t gone,” she said softly. And when Ruth asked what she meant, the girl only smiled, tilting her head as if listening to something too low for the rest of them to hear.

As the weeks passed, the air around the plantation grew heavier. It wasn’t just the heat or the stillness. It was something else, something that clung to the skin and settled in the lungs. The others began to avoid the hill entirely. They said the house watched them when they passed, that the shutters creaked, though no wind touched them. But Laya went there often. Every few days she’d wander up the hill barefoot, her plain white dress brushing the weeds, her doll clutched against her chest. She never stayed long, but when she returned, she’d be quiet for hours, as if she’d been listening to something no one else could hear.

Ruth tried to stop her once. “Don’t go up there, baby,” she pleaded. “Ain’t nothing waiting for you but pain.”

Laya just smiled faintly. “It don’t hurt no more. It just remembers.” When she said it, Ruth swore her voice didn’t sound like her own. It carried a low, steady rhythm that sent a chill crawling up her spine.

That night, Ruth told Mabel what she’d heard. The old woman didn’t answer right away. She was sitting by the fire, her hands folded tight in her lap. “She’s changing,” Ruth whispered. “Like she’s half here, half something else.”

Mabel shook her head. “She ain’t turning into no spirit. She just full of what he left behind. That kind of poison don’t die quick.”

But even Mabel couldn’t shake the unease. The next morning she found Laya sitting near the creek, arranging small stones into a perfect circle. The water shimmered pale in the sunlight, and every so often the girl would dip her fingers into it, tracing ripples until they vanished.

“What you making, honey?”

Laya looked up. “A place for him to rest.”

Mabel’s heart sank. “You mean your daddy?”

The girl nodded. “He talked in my sleep. Say he can’t find the door, so I’m making him one.”

Mabel crouched beside her, gently touching her arm. “You don’t owe him nothing, child. You hear me? You don’t got to open no door for the man who closed everyone you had.”

Laya’s eyes met hers, calm, distant, and far too old for her face. “Maybe he ain’t the only one need rest.”

That evening, when the sun dipped low, the women saw her standing at the edge of the field again, facing the big house. Her hair moved in the breeze, her figure small against the dying light. “Laya,” Ruth called. “You come back now.”

But the girl didn’t move. She raised her hand slowly as though waving to someone unseen. Then she whispered something that carried faintly on the wind. “Papa says it’s time to be quiet again.” When she turned back, her eyes looked different, emptier, softer, as if something had settled behind them. Mabel’s hands trembled as she drew the child into her arms, whispering a prayer she couldn’t finish, because deep down she understood. The man’s body might have vanished into the hill, but his voice hadn’t, and now it spoke through hers.

The winter that followed was thin and gray. The fields stood bare, the river ran low, and a frost settled across the plantation like a shroud. Most nights the quarters went to sleep early just to keep warm. But sometimes when the wind came down from the hill, they heard something that kept them awake. It wasn’t the cry of an animal or the creek of the trees. It was humming. A low, steady hum that drifted across the empty fields, carrying with it a tune that didn’t belong to anyone still living. Ruth said it was the wind. Mabel knew better.

She found Laya standing outside one night, facing the direction of the big house, her breath rising white into the cold. The girl was humming softly, rocking slightly on her heels, her doll tucked under her arm. “What you doing out here, baby?” Mabel asked gently.

Laya didn’t turn. “He says it’s lonely up there. The quiet too heavy.”

Mabel’s heart thudded. “Ain’t nobody up there, Laya.”

The girl finally looked back, her lips pale, her eyes reflecting the faint moonlight. “That’s what you think.”

The next morning, strange things started to happen in the quarters. The women would find their tools rearranged, their laundry pulled from the lines, their water buckets knocked over. The men said it was rats or wind, but Mabel saw the pattern, everything disturbed in the same precise way the master used to inspect. When she asked Laya about it, the girl only said, “He don’t like mess.”

The others began to keep their distance from her. They still cared for her, but fear had crept into their tenderness. She had a way of standing too still now, of looking through people rather than at them. Her small voice, once soft and uncertain, carried a tone of command that made even the strongest among them freeze for a moment before remembering she was only a child.

One evening, Ruth found her in the yard talking to no one. Her back was to the light, her shadow long against the dirt. “Who you talking to, baby?” Ruth asked.

Laya didn’t answer at first. Then she said, “I told him to stay quiet. He listened sometimes.”

Ruth swallowed hard. “He gone, Laya. You hear me? He gone for good.”

The girl smiled faintly. “Then why you whisper his name when you scared?”

Ruth took a step back. The air between them felt colder somehow that night. She told Mabel, “That child carrying something that ain’t hers.”

Mabel didn’t disagree. “Ain’t her fault,” she said quietly. “She just the echo. The rest of us, the ones who remember, we’re the walls that make it bounce.”

The next day, Laya stopped answering to her name altogether. When Mabel called her, she’d look up slowly, tilt her head, and say, “That’s what she used to call me.”

“Who, baby?” Mabel asked, dread creeping up her spine.

Laya smiled, soft as a prayer. “Mama.” And then she went back to humming, her voice the same calm rhythm the master once used when he spoke before he broke someone.

By the time the frost began to melt, Mabel knew she couldn’t wait any longer. Whatever had settled inside the girl was spreading, quiet, steady, like water under a door. The others had stopped looking her in the eye. Even the children avoided her shadow, and Laya, once restless and curious, now moved through the days like she was made of smoke.

One morning, Mabel found her sitting by the fire, staring into the flames. “You eat yet?” she asked. Laya didn’t answer. Her lips moved, but no sound came. Mabel knelt beside her. “Baby, talk to me.”

Laya blinked slow and heavy. “He don’t like me talking too loud,” she whispered.

Mabel’s breath caught. “Ain’t no one here to tell you what to do.”

The girl turned, eyes pale in the firelight. “He’s still here.”

“Where?”

“Everywhere.”

That word chilled Mabel more than any winter wind. That evening, she went to Ruth’s cabin. “We taken her to the river,” she said. “Tonight.”

Ruth froze. “The same river they buried her mama by.”

Mabel nodded. “She need to see where love stopped and sorrow started. Maybe then she’ll let go of what ain’t hers.”

They wrapped Laya in a shawl and led her through the dark fields. The moon hung low, half hidden by clouds. The air was thick and wet, the smell of cypress and silt rising from the riverbank. When they reached the spot, Laya stopped. “This where mama sleep,” she said softly.

Mabel nodded. “That’s right.”

The girl crouched beside the muddy edge, her fingers tracing circles in the wet earth. “She said papa cried when they put her here.”

“That ain’t crying, baby,” Mabel said. “That was guilt. Ain’t the same thing.”

Laya was quiet for a long moment. Then she whispered, “He still want me to say sorry.”

Mabel knelt beside her, took her hands in her own. “You don’t owe that man no sorry. You hear me? He the one should have begged you for it.”

The girl looked up, eyes glassy but calm. “If I don’t say it, he don’t sleep.”

“Then let him stay awake,” Mabel said. “Let him walk them halls forever. That’s his burden, not yours.”

The wind shifted then, carrying the faintest sound, a single piano note, distant and low, like the memory of something that refused to die. Ruth crossed herself. “Lord, he’s still calling her.”

Laya rose to her feet. Her face was unreadable now. “He say he’s sorry,” she murmured.

Mabel’s voice broke. “He ain’t got the right.”

But the girl stepped closer to the water, her reflection trembling across the surface. “He say he can’t find the door. He want me to open it.”

“Don’t you dare,” Mabel warned.

Laya turned her head, the moonlight catching her hair. “Maybe I’m the door.” Then she pressed her palms flat against the water. It rippled outward, slow and silent, until the surface turned white as milk. The river seemed to hold its breath. The ripples spread outward from Laya’s hands, glowing faintly in the moonlight, a pale shimmer rolling across the black water. Mabel and Ruth stood frozen behind her, afraid to move, afraid to speak.

“Laya,” Mabel whispered, “Come back now. That water too cold. You hear me?”

But the girl didn’t move. She knelt there, palms pressed flat against the surface, her reflection trembling like a living thing. The white sheen grew brighter, swirling around her fingers, climbing up her arms like veins of light. “He say he tired,” Laya murmured. “He say he can’t rest till I forgive him.”

Mabel’s heart thudded in her chest. “You don’t owe him that. He don’t deserve peace.”

The girl’s voice was calm, detached, as if she were listening to something far away. “Maybe I do. Maybe if I let him rest, he stopped talking to me.”

Ruth took a step forward. “And if you don’t?”

Laya looked up, her eyes distant, unfocused. “Then maybe I’ll go where Mama went. Maybe it quiet there.”

The air around them grew heavy, thick with mist rising from the river. It swirled around the girl’s small frame, catching the moonlight in strange ways, like smoke made of bone dust. The surface of the water shimmered white, milky, and still.

“Laya!” Mabel shouted, rushing forward. She grabbed the girl’s shoulders, trying to pull her back. But Laya didn’t resist. She only turned her head slowly and said almost gently. “He says it don’t hurt no more.” And then she smiled. It wasn’t a child’s smile. It was too knowing, too tired, the kind of smile that belongs to someone who seen the worst of love and still chooses to meet it halfway.

A low rumble rolled through the ground. The river churned suddenly, bubbles breaking the surface, the water swirling white and red in the moonlight. Mabel yanked her backward, both of them falling hard into the mud. When they looked up again, the glow was gone. The river had gone still, black and calm as before. Only the faintest white residue lingered at the edge, thick as cream.

Ruth dropped to her knees, breath ragged. “What in God’s name?”

But Laya was lying quiet in Mabel’s arms, her breathing shallow, her face pale but peaceful. Her small hand still dripped water that gleamed faintly before soaking into the ground. Mabel cradled her close, whispering over and over, “You still here, baby? You still here?”

Laya’s eyes fluttered open, unfocused. “He quiet now,” she whispered. “He gone.” Then softer. “But he say thank you.”

Mabel felt something inside her break, not from fear, but from understanding. The girl hadn’t freed him out of forgiveness. She’d freed him because she couldn’t carry him any longer. The river went still again, and for the first time since the master’s death, the air on the plantation felt lighter, like something vast had finally exhaled. But when Mabel looked down, the girl’s lips were blue, and her pulse was fading fast.

“Hold on, baby,” she pleaded, rocking her gently. “Hold on.”

Laya’s mouth moved, barely a whisper. “Mama, waiting.” And then her body went slack, her small hands slipping from Mabel’s grasp and falling into the water, leaving a faint white ripple spreading across the surface like milk poured into the dark.

The world seemed to stop when the ripples faded. The river went black again, swallowing the last trace of white. Mabel sat in the mud, holding Laya’s small, still body against her chest. The cold had settled deep into her bones, but she didn’t feel it. All she felt was the weight of the child that had never truly been hers and the quiet that had followed her everywhere since she’d lost her own.

Ruth stood nearby, trembling. “We got to move her,” she said softly. “We can’t leave her here.”

Mabel didn’t answer. Her eyes were locked on the water, where faint streaks of milk still drifted in slow circles, glinting under the moonlight. Finally, she whispered, “It took her gentle. At least it did that much.”

They wrapped the girl in her shawl and carried her back through the fields. No one spoke. The grass brushed their legs like hands reaching from the dark. In the distance, the house stood silent against the sky, a black shape with no light left inside. By the time they reached the quarters, dawn was bleeding into the horizon. The others gathered wordlessly, faces pale and wet. They laid Laya by the hearth, her hair damp and tangled, her lips faintly parted.

“She’s just sleeping,” one of the younger women whispered.

But Mabel shook her head. “She’d done more than sleep.”

When the sun finally rose, the world seemed to shift. The air lightened, the fields, dead and quiet for months, filled with bird song again. Even the river seemed to run clearer. For the first time, the plantation breathed. But peace has a price.

Three nights later, Ruth woke to the sound of footsteps outside. Soft, slow, barefoot steps. She sat up, heart pounding, and saw the faintest light flickering beyond the window. A child’s shadow moved across the yard. She ran to Mabel’s cabin. “You hear that?”

Mabel listened. The steps came again, padding through dirt, stopping, turning, and then a voice. Low, distant, but unmistakable. “Papa.”

Mabel’s blood went cold. She threw open the door. The yard was empty. The air was still, but on the ground near the fire pit lay a small handprint pressed into the dirt, perfectly shaped, faintly white.

For days after the others swore they saw her, standing by the river at dusk, sitting on the steps of the big house. Never close enough to touch, but always there, that small figure in white, her face unreadable, her eyes too calm for a ghost. Mabel never spoke of it, but she stopped praying out loud. Sometimes she’d wake before dawn and walk to the riverbank, kneel by the water, and whisper, “You got your peace, baby.” And when the morning mist rose over the river, white and soft as breath, she’d take it as her answer.

The house on the hill stayed empty after that. But on still nights, when the wind carried right, the faint sound of a piano could be heard again, playing just one slow, broken tune, and always after the final note, a child’s voice whispering, “I’m still listening.”

Years passed, and the Brantham plantation faded into ruin. The house on the hill sagged beneath the weight of its own silence. Windows broken, roof caved in, vines creeping through the parlor where a piano once stood. The fields were left untended, the soil dry and pale as bone. But the people still spoke her name, not loud, never in daylight, but in low voices by the fire when the nights turned cold. They said the master’s daughter never truly left, that she wandered between the cabins and the riverbank barefoot, her white dress glowing faintly in the dark. Some swore they saw her kneeling at the water’s edge, pressing her small hands to the surface, whispering to someone just beneath it. Others said she walked the halls of the big house, her footsteps light as dust, pausing by the piano as if waiting for a tune that would never start again.

The older folks called her the listening child. The younger ones called her the quiet girl. But the name that stayed, the one that turned to legend, was the milk daughter. They said the river still curdled white some mornings when the fog rolled in low, thick as breath. And if you stood too close, you could hear the faintest echo of her humming. A soft, broken melody carried by the mist, neither joyful nor mournful, just there, the way grief lingers in a room after the crying stops.

Mabel grew old. Her hands stiffened, her hair turned silver, but she never left that land. She tended the graves near the magnolia tree, and every year on the night the first frost came, she walked to the riverbank and lit a single candle. Not for the master, not for the wife, for the girl, the one who’d been both victim and vessel, who had carried cruelty like a voice inside her and found a way to quiet it.

One night, a child from the newer families followed her there. “Miss Mabel,” he whispered, “why you light that candle every year?”

She didn’t turn. Her eyes stayed fixed on the water where the candle flame trembled in the reflection. “Cuz some souls don’t rest where they die,” she said. “They rest where they forgive.”

The boy frowned. “She forgive him?”

Mabel’s voice cracked just slightly. “She let him go. That’s harder.”

As the years passed, the story changed. The names blurred. The truth softened as it always does. But the river kept its color. No one drank from it. No one washed their clothes there. It wasn’t cursed, they said, just remembered. And on certain nights, when the moon hung low and the air turned heavy, people claimed they saw a woman standing by the water, tall, calm, holding something small against her chest. Sometimes she looked like the master’s wife, sometimes like his daughter, sometimes like both. But she never spoke because the story had already said enough.

Time did what it always does. It buried what it could and left the rest behind. By the turn of the century, the Brantham name was gone from the county records. The land parceled and sold, the house long collapsed beneath kudzu and vines. But still no one built there. The fields remained empty, the soil strangely pale, and folks whispered that nothing would grow on ground that had known so much shame. The story lived on, though, not in books or church sermons, but in the way people talked about love and cruelty, as if the two were threads from the same torn cloth.

They said the master’s daughter had been born different, touched by something the world didn’t yet have a name for. But what broke her wasn’t her mind. It was how others chose to see it. Her gentleness had been mistaken for weakness, her confusion for defiance. And when her mother died, the world around her taught her one lesson too well. That love in that house came hand-in-hand with pain. What no one expected was that she would learn it so completely. That she’d turn that lesson inward until her own heart became a mirror for everything her father was too proud to face.

The women in the quarters used to say cruelty leaves a sound behind, like a bell struck too hard, echoing long after the hand that hit it is gone. They said some children are born close enough to hear that echo and some like Laya learned to speak in it. But what made her different wasn’t that she echoed her father’s voice. It was that in the end she chose to silence it.

Mabel lived long enough to see freedom come and then the world forget again. She died by the river, sitting in her chair, a candle burned down to wax at her feet. When they found her, she was smiling faintly. Her eyes turned toward the water. The mist that morning was thick and white. The preacher said her soul went easy, but the old women whispered something else, that she’d heard the girls humming again, soft and clear, just before the light left her eyes.

Years later, a traveler passing through the parish stopped to rest near the ruins of the Brantham House. He said he heard a piano playing faintly through the fog, just three notes, slow and uneven. When he followed the sound, there was nothing there but a broken window and a pale mark on the ground that looked like a child’s handprint. He left before nightfall. No one blamed him because the people who still lived near that land knew what the rest of the world didn’t. That sometimes the dead don’t stay to haunt. They stay to remind.

And the story of Laya, the master’s daughter, the quiet child, the one who carried his sins to the river and left them there, became not a ghost tale, but a warning. That cruelty, when passed down, does not die. It learns. It listens. And it waits for someone brave enough to let it go. Some stories don’t end with screams. They end with silence. A silence so complete it feels like the earth itself has stopped to listen. That was how the Brantham land died. Not in fire, not in blood, but in quiet.

No records remain of the family, no stones with their names carved into them. The river swallowed those years whole, leaving only whispers, the kind that drift through the cane when the wind moves slow. Folks say the water there still shines faintly white in the moonlight and that if you stand close enough you can see your reflection blur as if the river doesn’t just remember faces but tries to give them back. Some nights people still leave flowers by the bank. They don’t know who they’re for. The child, the mother, or the man who ruined them both, but they leave them anyway just in case forgiveness needs somewhere to land.

And if you listen long enough, you can still hear it. That same thin hum, soft and patient, carrying across the water like a lullaby meant for no one. It said the girl’s spirit never turned cruel. She didn’t haunt the land to punish or to frighten. She lingered to remind, to show that even in a world built on cruelty, a small mercy could still survive, even if it cost everything. Because mercy was what she gave him at the end. When she touched the river and let him rest, she freed the thing that had broken her, not out of love, but out of exhaustion, because hate is heavy, and some hearts, even the small ones, refused to carry it forever.

Mabel’s descendants kept that story alive long after the house fell. They told it to their children, not as a ghost tale, but as a lesson, about the weight of memory, about what happens when pain is handed down and called tradition. And they always ended it the same way. They said that when cruelty lives too long in one place, it doesn’t vanish. It changes its face, hides in smaller things, a harsh word, a raised hand, a silence that goes on too long. But it can still be broken. All it takes is one person willing to stop listening to it.

So when the fog rolls over the Brantham fields and the river glows pale beneath the moon, the people nearby still close their windows and whisper, “Let her rest.” And the night does. Because that’s what she’d been asking for all along. Not to be remembered for what she suffered, but for what she ended. The cruelty, the echo, the voice, and the silence that followed. Wasn’t just an ending. It was peace.

Some stories fade with time. This one didn’t. It stayed, not because of what was done, but because of what was left behind. The Brantham plantation is gone now. The river runs quiet. But silence has a memory, and cruelty has a way of finding new names, new homes, new hearts to live in. Maybe that’s why we tell stories like this one. Not to glorify pain, but to remember what it sounds like when someone finally refuses to pass it on. If you ever stand by a river and hear something humming low through the mist, don’t be afraid. It’s not a ghost. It’s a reminder that what we forgive, we free, and what we carry carries us back.

You’ve been listening to the Macabra Record. Subscribe and return for another story time for where history whispers and the past still breathes.

News

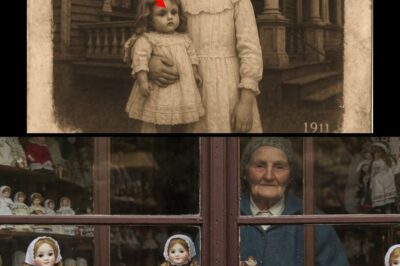

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze…

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze… In…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next Left Everyone Speechless…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next…

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn In the misty heart of the…

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras.

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras. In 1883, thirty…

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

End of content

No more pages to load