How Nero Turned a Teenage Boy Into His Dead Wife

The Imperial guards found him hiding in the abandoned villa’s wine cellar, clutching a small vial of poison in his trembling hand. This wasn’t some common criminal or political rebel; this was Sporus, barely 20 years old, once the empress of Rome, about to take his own life rather than face what the new emperor had planned for him in the Colosseum. To understand why death seemed like mercy compared to what awaited him, we need to go back three years to when a grieving, half-mad emperor first laid eyes on a teenage boy who looked exactly like his dead wife. What you are about to hear isn’t just another tale of Roman excess; it’s the most disturbing case of identity theft in human history, where the thief didn’t steal a name or fortune, but an entire person’s existence, surgically erasing one life to resurrect another. The most terrifying part is that everything you are about to read comes from official Roman records.

Rome, 65 AD. The most powerful man in the world has just become a murderer. Not through war or execution—those were everyday occurrences in the empire—but Emperor Nero had just killed his pregnant wife, Poppaea Sabina, with his own hands in their private chambers. Some sources say it was a single devastating kick to her swollen belly; others describe a brutal beating that left her hemorrhaging on the marble floor. Nero, suddenly realizing what he had done, screamed for physicians who couldn’t reverse death even for a god-emperor.

The woman who died that day wasn’t just any imperial wife. Poppaea Sabina had been Nero’s obsession, his muse, the one person who could match his grandiose view of himself. Contemporary accounts describe her as possessing almost supernatural beauty: amber-colored hair that caught light like spun gold, skin so pale it seemed to glow, and most distinctively, enormous, doe-like eyes that Roman poets compared to those of Venus herself.

Nero’s grief was not normal human mourning. When you command an empire of 60 million souls, when you have been told since childhood that you are descended from gods, and when reality itself bends to your will, the death of your beloved is not just loss—it is a personal insult from the universe, a boundary that dares to exist when you recognize no boundaries. Nero’s response to Poppaea’s death shocked even the jaded Roman aristocracy. He refused the traditional cremation, instead having her body embalmed with more spices than the entire Arabian Peninsula produced in a year. He had her corpse dressed in her finest robes and placed in a crystal sarcophagus where he could see her. Palace servants reported finding the emperor having full conversations with the body, setting places for her at dinner, and asking her opinion on matters of state.

The court physicians, those brave or foolish enough to approach him, tried to explain that grief could manifest in strange ways, but Nero wasn’t just grieving; he was fracturing. Sleep became impossible without massive doses of poppy wine. He would wake up screaming Poppaea’s name, convinced he could hear her calling from the next room. Food lost all taste unless it was prepared exactly as she had liked it. He ordered her personal chambers preserved exactly as she left them, down to the position of her hairbrush on the dressing table.

But the most disturbing behavior began about two months after her death. Nero started seeing her everywhere: in the face of a young slave girl bringing wine, in the profile of a senator’s wife at the games, in the features of prostitutes in Rome’s Caelian districts. He would stop mid-sentence during important meetings, staring at some random woman who bore even the slightest resemblance to his dead wife. More than once, he terrified innocent women by grabbing their faces, turning them toward the light, searching desperately for something that wasn’t there. The imperial household held its breath, waiting for this madness to pass. Instead, it intensified. Nero commissioned hundreds of paintings and sculptures of Poppaea, demanding artists capture not just her appearance but her essence. When they inevitably failed—how could paint and marble capture a living soul?—he would fly into rages, sometimes ordering the artist beaten, sometimes weeping like a child.

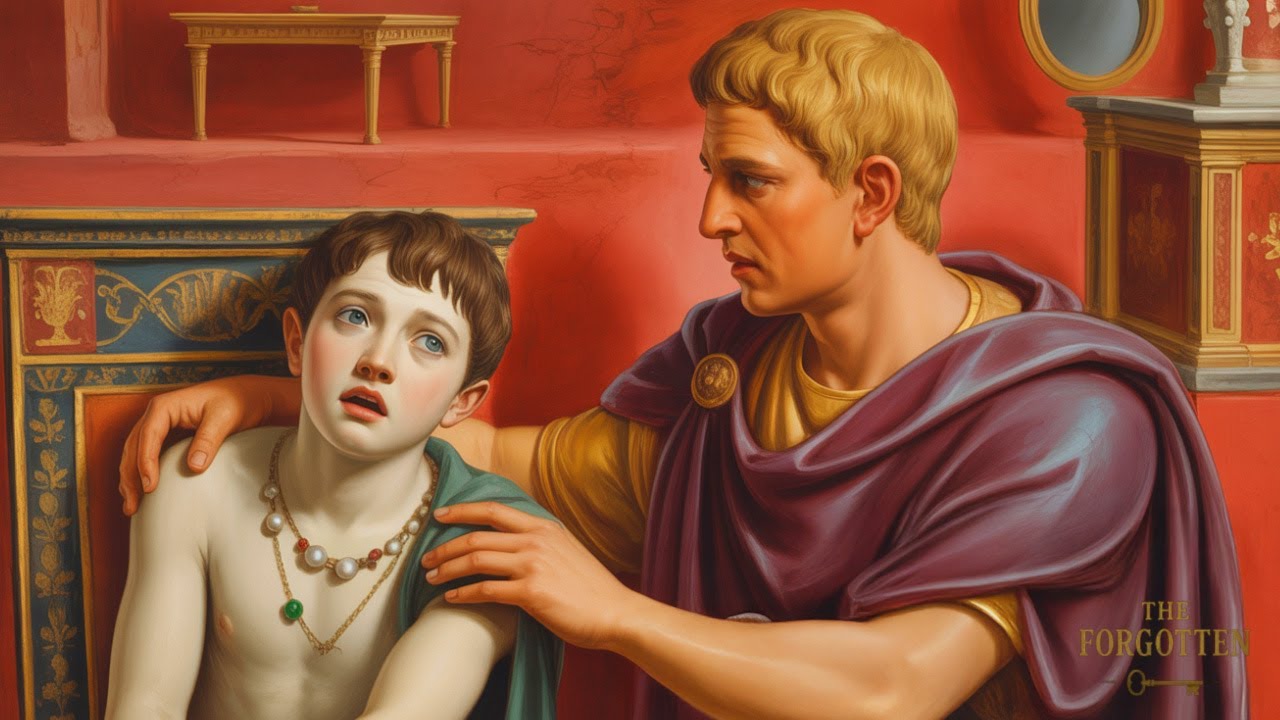

Then came that fateful day in late 65 AD when everything changed. Nero was reviewing administrative appointments, a mind-numbing task he usually delegated but was forcing himself to focus on as a distraction from his grief. A young freedman, recently promoted to a minor clerical position, was brought forward to be confirmed in his new role. The emperor looked up from the endless scrolls, and time stopped.

The boy standing before him, who could not have been more than 15, had Poppaea’s eyes. Not similar eyes, not a passing resemblance, but the exact same enormous, dark-lashed eyes that had captivated Nero from the moment he first saw her. The same delicate bone structure framed them, the same way of unconsciously tilting his head when nervous, even the same unusual amber flecks in the irises that caught the light from the oil lamps.

Nero rose from his throne so quickly that scrolls scattered across the floor. The court held its collective breath as the emperor approached the terrified boy, circling him like a predator studying prey. But there was something else in Nero’s expression: a desperate hope, a manic joy that was somehow more frightening than rage. “What is your name, divine Augustus?” Nero’s voice was barely a whisper. “I am Sporus.”

Sporus wasn’t just any slave. He had been born into the imperial household; his mother was a Germanic captive who died in childbirth. Raised in the labyrinthine servants’ quarters of the palace, he had been educated alongside the children of other imperial freedmen, trained in Greek and Latin, mathematics, and rhetoric. His delicate features and quick intelligence had marked him for administrative service rather than manual labor. But none of that mattered now. In that moment, Sporus ceased to exist as an individual; he became a canvas for an emperor’s delusion.

Nero’s examination continued for what witnesses described as an eternity but was probably only minutes. He touched the boy’s face, turned it to catch different angles of light, and ran fingers through his hair. Sporus stood frozen, intelligent enough to understand that his life balanced on a knife’s edge but not yet comprehending the full horror of what was about to unfold. Finally, Nero stepped back. The smile that spread across his face was described by one chronicler as the expression of a man who has discovered the secret of defeating death itself.

“Cancel the rest of today’s appointments,” Nero commanded, “and summon my personal physicians. Tell them to prepare their finest chambers and their sharpest instruments. We have work to do.”

The transformation of Sporus didn’t begin immediately with surgery; that would come later. First, Nero needed to study his subject to understand every way this boy could be molded into his lost love. For days, Sporus was kept in luxurious chambers adjacent to Nero’s own, subjected to endless examinations and measurements. The emperor brought in his most trusted artists, the ones who had painted Poppaea from life. They were ordered to study Sporus and create comparative sketches, noting where he matched the dead empress and where he differed. Nero pored over these studies with the intensity of a scholar examining sacred texts, making notations, and planning modifications.

It wasn’t just physical appearance Nero was analyzing. He had Sporus speak for hours, listening to his voice, correcting his pronunciation, and teaching him Poppaea’s distinctive way of drawing out certain vowels. He tested the boy’s walk, his gestures, the way he held his hands when sitting. Every deviation from Poppaea’s mannerisms was noted for correction.

The psychological torture had already begun. Sporus was forbidden to use his own name. Servants were instructed to address him as “Lady” or “Mistress.” His simple tunics were replaced with flowing stolas in Poppaea’s favorite colors. He was taught to apply cosmetics, not the simple touches appropriate for a Roman youth, but the elaborate makeup of a noble woman. Can you imagine waking up each morning, looking in the polished bronze mirror, and seeing your own face being systematically erased? The servants who attended Sporus during this period later reported that he barely spoke, barely ate, and moved through his days like someone in a waking nightmare.

He didn’t resist. How could he? One word of complaint would mean death, or worse. By now, Sporus had learned what Nero intended. The emperor hadn’t hidden his plans; in fact, he spoke of them openly, excitedly, like an artist describing a masterpiece in progress. The physicians had been consulted, the procedure had been explained: Sporus was going to be physically transformed into a woman through castration and surgical modification. This wasn’t just removing masculinity—Roman eunuchs were common enough in certain roles—this was something unprecedented: an attempt to surgically create a woman from a man, to rebuild Sporus’s body into an approximation of feminine form.

The physicians, threatened with death if they refused and promised immense rewards if they succeeded, had devised procedures that went far beyond simple castration.

The night before the surgery, something remarkable happened. Nero visited Sporus in his chambers, bringing with him a small wooden box. Inside was a ring: Poppaea’s wedding ring, a massive emerald surrounded by pearls. “Tomorrow,” Nero said, sliding the ring onto Sporus’s finger where it hung loosely, “you will be reborn. You will become who you were always meant to be, and I will love you as I loved her.” Sporus finally spoke, his voice barely audible: “Will it hurt?” For just a moment, something almost human flickered in Nero’s eyes. Then it was gone, replaced by that manic certainty. “Birth always hurts,” he replied, “but what emerges is beautiful.”

The surgery took place in a specially prepared chamber in the palace’s medical wing. The exact details are mercifully sparse in historical records, but we know it lasted hours. The screams, according to one account, could be heard three corridors away despite the thick walls. Nero waited outside, pacing like an expectant father, occasionally shouting encouragement through the door as if his words could somehow ease the agony.

The recovery took months. Infection was a constant threat in an age before antibiotics. The modifications were extensive enough that Sporus had to relearn basic functions. Through it all, Nero was a constant presence, supervising the healing, adjusting dosages of pain-dulling poppy extracts, even helping change bandages with his own imperial hands. This tender care might seem touching until you remember its purpose: Nero wasn’t nursing a person back to health; he was crafting an object to fulfill his obsession. Every gesture of kindness came with a reminder of what Sporus was becoming. Nero would sit by his bedside, reading aloud from Poppaea’s favorite poems, telling stories about her as if Sporus should remember them, gradually blurring the line between who Sporus was and who he was being forced to become.

The physical healing was one thing; the psychological transformation was another. As Sporus recovered, an army of tutors descended upon him. He learned to walk in the smaller, swaying steps considered proper for a Roman matron. His hands were trained to move with studied grace, to hold a wine cup delicately, to gesture while speaking in the restrained manner expected of imperial women. The voice training was perhaps the most intensive. Hour after hour, Sporus practiced speaking in higher, softer tones, learning to modulate his voice to sound feminine. He was taught Poppaea’s favorite phrases, her way of laughing, even her specific intonations when addressing different members of court.

A wardrobe was commissioned, not just any women’s clothing, but exact replicas of Poppaea’s favorite garments. The Imperial seamstresses, working from preserved samples, recreated her most iconic dresses. Jewelers reset her personal collection to fit Sporus’s slightly different proportions. Even her perfumes were recreated by mixing the same rare oils and resins.

But clothes and jewels were just the beginning. Sporus had to learn the complex rituals of a Roman noblewoman’s day: the hours-long morning beauty routines, the elaborate hair styling that required a team of servants, the proper way to recline at dinner parties, and how to engage in the witty but never-too-clever conversation expected of imperial women. Wait, it gets even more disturbing.

Nero didn’t just want Sporus to look and act like Poppaea; he wanted him to be Poppaea. The boy was required to study her history, her childhood in Pompeii, her first marriage, her rise through Roman society. He had to memorize names of her friends, her favorite foods, her opinions on poetry and politics. When Nero reminisced about shared experiences, Sporus had to respond as if he remembered them too.

The first public appearance came about six months after the surgery: a small dinner party just Nero’s closest advisers and their wives. The reaction when Sporus entered the room, dressed in one of Poppaea’s distinctive purple gowns, her jewelry glittering in the lamplight, was electric. Conversation stopped mid-sentence, wine cups frozen halfway to lips. Everyone had heard rumors, but seeing the transformation was something else entirely. The resemblance was uncanny. In the soft lighting, with cosmetics expertly applied, Sporus looked eerily like the dead empress. The way he moved, the tilt of his head, even the way he smiled—it was all Poppaea, or rather, it was a performance of Poppaea so complete that for moments at a time, even cynical courtiers found themselves forgetting the truth.

Nero beamed like a proud artist revealing his masterpiece. He kept one hand possessively on Sporus throughout the evening, introducing him as “my beloved Sabina,” using Poppaea’s family name. The guests, masters of political survival, played along with enthusiasm that bordered on the hysterical. They complimented “Sabina’s” beauty, asked after her health, and included her in conversations as naturally as if the last months had been a strange dream and Poppaea had never died.

But you can’t fool everyone forever. Tacitus, writing years later, recorded the observations of those forced to participate in this charade. They noted how Sporus’s hands, despite all the creams and treatments, remained slightly too large for a woman; how his shoulders, beneath the flowing fabric, retained a masculine broadness; how, occasionally, when he forgot himself, his natural voice would break through the practiced feminine tones.

More heartbreaking were the moments when Sporus’s own personality emerged. Witnesses described catching glimpses of a sharp intelligence, a dry wit, a profound sadness that had nothing to do with Poppaea. But these moments were quickly suppressed. Any deviation from the role meant punishment: not physical abuse, which might mar the illusion, but psychological torment. Nero would grow cold, withdraw affection, or threaten to find a “better Poppaea” if this one couldn’t perform adequately.

The wedding announcement shocked even those who thought they’d seen the depths of Nero’s madness. It came in early 67 AD, proclaimed throughout Rome as if it were completely normal for the emperor to marry his surgically feminized teenage freedman. The ceremony would be a full state occasion, with all the traditional Roman rituals, treating this union as legitimate as any imperial marriage. The preparations were grotesque in their normalcy. Wedding planners consulted ancient traditions, priests prepared the proper sacrifices, and the route for the procession was decorated with flowers and garlands. Invitations were sent to every senator, magistrate, and foreign dignitary in Rome. Declining was not an option.

The wedding day itself was surreal. Sporus was dressed in the traditional saffron-colored veil of a Roman bride, his face painted with the ceremonial cosmetics. The dowry—a massive fortune in gold and property—was formally transferred. Contracts were signed with the same legal language used for any marriage, despite the biological impossibility of the union producing heirs. Nero played his role as groom with disturbing sincerity. He performed the traditional rituals, spoke the ancient vows, and even carried Sporus over the threshold in the manner prescribed by custom.

The wedding feast that followed was lavish beyond description: peacocks stuffed with songbirds, wine from Caesar’s own cellars, and entertainment by the finest musicians and dancers in the empire. Throughout it all, the Roman elite maintained their frozen smiles and offered their congratulations. Gifts poured in—jewelry for the new “empress,” household goods for the imperial couple, even fertility amulets in a display of either dark humor or desperate attempts to please the emperor. Senators gave speeches praising the beauty of the bride and the happiness of the union. Poets composed epithalamiums celebrating the marriage.

But behind the facade, everyone understood they were witnessing something unprecedented and deeply wrong. This wasn’t just another of Nero’s excesses; this was a fundamental violation of Roman values, natural law, and human dignity. Yet, they applauded, smiled, and toasted the happy couple, because the alternative was death.

Life as Nero’s empress was a daily performance that never ended. Sporus woke each morning in Poppaea’s chambers, surrounded by her possessions. Servants who had once attended the real Poppaea now dressed him in her clothes, styled his hair in her favorite arrangements, and applied cosmetics to maintain the illusion. Every gesture, every word, every expression had to be calculated to maintain the fiction.

The public appearances were perhaps the worst. Nero insisted on taking his new wife everywhere: to the theater, the races, religious ceremonies, and state functions. Sporus sat in the empress’s box at the Colosseum, carried in the empress’s litter through the streets, and received the ceremonial honors due to an Augusta. The Roman people, always eager for spectacle, gathered to stare at this impossible creature: a boy transformed into a ghost of a dead woman.

During Nero’s grand tour of Greece in 67 AD, the performance reached new heights of absurdity. The Greeks, eager to please their Roman conquerors, treated Sporus with all the deference due to an empress. He presided over banquets, attended Nero’s artistic performances, and even participated in religious ceremonies reserved for the emperor’s wife. In Olympia, priests prayed for the couple to be blessed with children, maintaining the fiction even in the face of biological impossibility.

But it was in the private moments that the true horror of Sporus’s existence became clear. Nero expected him to respond to intimacy not just as a woman, but as Poppaea specifically. He had to know her preferences, mirror her responses, and even recreate private jokes and tender moments that had belonged to a dead woman. Any failure to maintain the illusion could send Nero into either violent rage or, worse, cold disappointment that felt like death itself to someone whose survival depended entirely on pleasing a madman.

The other members of the Imperial household treated Sporus with a mixture of pity, fear, and disgust. He existed in a strange liminal space: neither man nor woman, neither slave nor free, neither alive in his own right nor truly the person he was impersonating. Palace servants whispered about seeing him alone in the gardens at dawn, standing completely still as if he had forgotten how to exist when not performing.

There were escape attempts, of course. How could there not be? But where could someone so recognizable run? Sporus’s transformed appearance, his feminine presentation, and the imperial jewelry he was required to wear at all times all marked him as clearly as any brand. The one recorded attempt ended with the capture of the accomplices who tried to help him. They were crucified in the palace courtyard where Sporus could see them from his window—a reminder that even death wouldn’t free him from Nero’s obsession.

Yet perhaps the cruelest aspect of Sporus’s captivity was the moments of genuine kindness from Nero. The emperor, in his madness, seemed to truly believe he had resurrected his beloved. He would shower Sporus with gifts, spend hours in seemingly tender conversation, and protect him from any slight or insult. To outside observers, it might have looked like a loving relationship. But how can there be love when one person has been surgically and psychologically restructured to fit another’s delusion?

Historical accounts suggest that over time, Sporus developed what we might now recognize as a severe dissociative disorder. He began referring to himself as Poppaea even when not in Nero’s presence. Servants reported finding him having conversations with mirrors, speaking in two voices—his own and the feminine persona he had been forced to adopt. The boundaries between Sporus and the role he played became increasingly blurred, perhaps as the only way his mind could cope with the daily trauma of his existence.

Then came the spring of 68 AD, when Nero’s world began to collapse. Rebellions erupted across the empire, the Senate declared him an enemy of the state, and the Praetorian Guard abandoned him. As Nero fled Rome with only a handful of loyal servants, Sporus was among them. Even facing death, the emperor couldn’t leave behind his artificial Poppaea.

Those final days in the villa outside Rome were a descent into pure madness. Nero alternated between grandiose plans for escape and theatrical preparations for suicide. Through it all, Sporus remained by his side, still playing the role of devoted wife even as the empire crumbled around them. Witnesses described Nero clinging to Sporus, calling him “my only love, my resurrection,” begging him to die together like ancient, tragic lovers.

When news came that capture was imminent, Nero finally chose death. But even in his last moments, the performance continued. He asked Sporus to begin the ritual lamentations for his death, to mourn him as Poppaea would have mourned. As Nero pressed the dagger to his throat with trembling hands, Sporus helped guide it—perhaps the only genuinely merciful act in their entire twisted relationship.

With Nero dead, Sporus’s nightmare should have ended. Instead, it entered a new phase. He was now a living symbol of Nero’s excesses, a valuable prize for whoever claimed power next. The generals fighting for the throne each saw him differently: as a trophy, a curiosity, a potential legitimizing link to the previous regime, or simply as an object of fascination.

First came Galba, the elderly general who briefly claimed the purple. He treated Sporus with cold courtesy, keeping him in the palace but largely ignoring him. For a few months, Sporus lived in a strange twilight existence, still dressed as a woman (what else could he do after years of transformation?), still called Sabina, but without the intense focus of Nero’s obsession. But Galba’s reign lasted only seven months before he was murdered in the Forum.

His successor, Otho, had known Poppaea personally; in fact, she had been his wife before Nero stole her. Otho’s interest in Sporus was therefore particularly disturbing. Did he see in the transformed boy an echo of his lost love, a chance for revenge against Nero’s memory? Historical sources suggest Otho treated Sporus as a legitimate widow, even promising to marry him, though his reign was too brief for this plan to materialize.

When Otho committed suicide after losing the battle of Bedrium, Sporus passed to the victor, Vitellius. It was under Vitellius that Sporus’s story reached its final, brutal chapter. Vitellius was a different kind of emperor—crude, gluttonous, caring nothing for the refined cruelties of his predecessors. To him, Sporus was neither a person nor a valuable object, but a potential source of entertainment for the mob.

Here is where the story takes its darkest turn. Vitellius announced that Sporus would perform in a public spectacle in the Colosseum—not as a spectator in the Imperial box, but as a participant in the games. The plan was hideously creative: Sporus would be forced to reenact the myth of Proserpina, the maiden abducted by Pluto to the underworld. In this fatal performance, he would be abducted by gladiators dressed as demons and subjected to public rape before being killed.

When Sporus learned of this plan, he finally found the strength that had eluded him for years. Rather than submit to this final degradation, he chose death on his own terms. The exact method is debated—some sources say poison, others suggest he opened his veins in the traditional Roman manner—but all agree that he died by his own hand, finally escaping the role he had been forced to play. He was approximately 20 years old.

The tragedy of Sporus raises profound questions about identity, autonomy, and the corruption of absolute power. Here was a person systematically destroyed and rebuilt to serve another’s delusion. Every aspect of his existence—physical, psychological, social—was violated and reshaped. He became a living ghost, forced to impersonate someone he had never met, to love someone who had destroyed him. What makes his story particularly haunting is how completely we have lost the real Sporus. We don’t know his thoughts, his dreams, or his personality before Nero’s attention fell upon him. That person was so thoroughly erased that even his name is uncertain. Sporus itself might have been a cruel nickname, meaning “seed” or “sewn thing,” emphasizing his transformation. The boy who entered Nero’s presence that day effectively ceased to exist, replaced by a performance that continued until death finally released him.

Modern historians debate whether Sporus ever experienced moments of agency within his captivity. Some point to his final suicide as his one true act of self-determination. Others note small resistances: the moments when his real voice broke through the practiced feminine tones, the escape attempt, and the choice to help Nero die rather than prolonging the emperor’s life and his own captivity.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of Sporus’s story is how many people were complicit in his torture: the physicians who performed the surgery, the tutors who trained him, the courtiers who pretended he was Poppaea, and the servants who dressed him each day. Hundreds of people participated in maintaining this cruel fiction. Each of them made the choice to prioritize their own survival over the humanity of a teenage boy.

The story of Sporus serves as a reminder that power without conscience creates horrors beyond imagination. When reality itself becomes subject to the whims of authority, when human beings become raw material for others’ fantasies, and when entire societies participate in obvious fictions to appease tyrants, the results are invariably tragic.

In the grand narrative of Roman history, Sporus is often reduced to a footnote—just another example of Nero’s excesses. But he was a human being whose life was stolen, whose identity was erased, whose body was mutilated, and whose every waking moment became a performance in someone else’s tragedy. He deserves to be remembered not just as a victim, but as a person who endured unimaginable circumstances and finally, in his last act, chose freedom over further degradation.

The ruins of Nero’s palace still stand in Rome, buried beneath later constructions. Somewhere in those ruins are the chambers where Sporus lived his stolen life, where he stood before mirrors that reflected back a stranger, where he practiced speaking in a voice not his own. The stones remember, even if history has largely forgotten the boy who was forced to become a ghost.

News

Three Times in One Night – While Everyone Watched (The Vatican’s Darkest Wedding)

Three Times in One Night – While Everyone Watched (The Vatican’s Darkest Wedding) Inside the apostolic palace of the Vatican…

The Breeding Barn Horror: 42 Women Who Vanished Into Evil

The Breeding Barn Horror: 42 Women Who Vanished Into Evil Welcome to history. Picture this: a remote stretch of Missouri…

The Mother Who Forced Her 5 Sons to Breed — Until They Chained Her in The “Breeding” Barn

The Mother Who Forced Her 5 Sons to Breed — Until They Chained Her in The “Breeding” Barn Deep in…

A humble mother helps a crying little boy while holding her son, unaware that his millionaire father was watching

A humble mother helps a crying little boy while holding her son, unaware that his millionaire father was watching Under…

What the Ottomans did to Christian nuns was worse than death!

What the Ottomans did to Christian nuns was worse than death! Imagine the scent of ink from ancient parchments still…

The Whitaker Boys Were Found in 1984 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans at All

The Whitaker Boys Were Found in 1984 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans at All The Blackwood National Forest…

End of content

No more pages to load