German “Comfort Girl” POWs Cried Over Their First American Meal in U.S Camps

Nisel Brena was 21 years old and she had served as a clerk for a small German army unit in France, handling documents and supply records. When her unit surrendered to the Americans, she expected to be kept somewhere in Europe. But within weeks, she and several dozen other women were told they would be sent overseas.

None of them understood exactly where until they reached the port and saw the American ships waiting. The guards told them they were going to the United States. The news felt strange, almost impossible to believe, because America had always sounded like another world entirely, far away, rich and untouched by war.

The crossing took almost 2 weeks. The sea was rough, and the prisoners slept in bunks stacked three high, guarded by soldiers who spoke little German, but treated them with a kind of distant politeness. But before we continue, if you want to hear more incredible and untold stories from the history, make sure to like the video and hit the subscribe button and tell me in the comments what country you’re watching from.

It’s really fascinating to see how far these forgotten stories can reach. All right, they were given regular meals, bread, stew, fruit, and even chocolate, which already felt luxurious compared to what they had eaten in Germany. Leisel noticed that even the guards ate the same food and that there was always enough. For the first time in years, she didn’t feel hungry at night.

When the ship finally reached the coast, the prisoners were put on trains that carried them deep into the country. Through the windows, Leisel saw wide fields, small towns, and roads lined with trees. Everything looked orderly and untouched by bombing. It was quiet in a way that Europe hadn’t been for years.

After several days of travel across the United States, the train carrying Leisel Brener and the other German women finally slowed down near a small town surrounded by open land. Through the windows, Leisel saw wide fields, fences, and a few wooden buildings that looked newly built. The guards told them this was their destination.

The women gathered their belongings, mostly small bags with clothes and letters, and stepped off the train into the warm afternoon air. The place felt strange, not threatening, not welcoming, just quiet and organized. There were guards posted near the gates, but they did not shout or hurry the prisoners.

Everything happened in an orderly, calm way. Trucks waited to take them from the station to the camp, which was a few miles away. As the trucks moved along the dirt road, Leisel noticed how clean everything looked compared to Europe. The farms were intact, the roads smooth, and there were no burned buildings or ruins anywhere. She felt a mix of relief and disbelief.

It was hard to imagine that this country had been part of the same war that had destroyed so much of Germany. When the trucks reached the camp, the prisoners were told to line up for registration. American officers checked their names against a list and gave each woman a tag with her number. The process took time, but there was no shouting, no pushing, and no harsh treatment.

Once the paperwork was done, they were taken to a row of wooden barracks that would serve as their living quarters. Each barrack had several rooms with iron beds, thin mattresses, and small wooden cabinets. It was basic, but everything was clean. The windows opened easily, and the air smelled of dry wood and soap. The women were then shown the washroom.

To Leisel, it was the most surprising part of the entire camp. There were sinks with running water, mirrors, and showers with proper drains and curtains. Hot water came out of the pipes almost immediately, something she had not experienced in years. In Germany, by the end of the war, even simple washing had become difficult. Soap was rare, and water was often cold or rationed.

Here, there was enough for everyone. After the inspection, each woman received new clothes, plain khaki uniforms marked with PW on the back. They were loose and practical, but freshly washed and folded. The guards explained the camp rules through an interpreter. Work assignments, meal times, mail schedules, and restrictions on movement. Everything had its place and time.

Leisel realized that the structure made things easier. There was no confusion, no uncertainty, and everyone knew what to expect each day. That evening, the group was led to the dining hall. It was a large building with long wooden tables and benches lined up in rows.

The smell of cooking drifted from the kitchen, and though none of the prisoners knew what kind of food was being prepared, it was warm and comforting. They had not eaten since morning, and hunger mixed with nervousness as they waited quietly for the signal to line up. Some whispered to each other, wondering what the Americans would serve, but most stayed silent, watching the guards and trying to understand the new routine. When the doors opened, the women filed in one group at a time.

The American cook stood behind the serving line, wearing white aprons and handing out trays. Lizel held hers tightly, unsure if she was supposed to speak or stay silent. She had spent months expecting harsh treatment, but instead everything was calm, polite, and efficient.

She noticed that even though they were prisoners, no one insulted or humiliated them. The guards stood at their posts watching, but not interfering. The room was bright, the smell of food strong, and the sound of metal trays clattering filled the air. Leisel found a seat with a few other women from her unit. For the first time since leaving Europe, she felt the tension in her shoulders begin to ease. She still did not know what life in this camp would truly be like.

But in that moment, surrounded by order and quiet voices, she sensed that it would be different from what she had imagined on the ship. She didn’t know yet that the meal she was about to eat, would be one of the most memorable moments of her life. But she could already tell that this place, even behind fences, was nothing like the prisons she had feared.

When the signal was given to begin dinner, the line of German women started to move slowly toward the serving counter. Leisel Brener followed the others, holding her tray with both hands. The room was warm and filled with the steady sounds of movement, footsteps, trays sliding on metal and the low hum of quiet conversation.

The smell of cooked food drifted through the air, stronger now that they were closer to the kitchen. None of them had eaten much that day, and after the long journey and the registration process, their hunger was sharp, but mixed with hesitation.

They still didn’t know what kind of food the Americans would give them, or how they would be treated during meal time. When Lizel reached the counter, an American cook wearing a white apron placed a large spoonful of mashed potatoes on her tray, followed by a slice of roast beef, cooked vegetables, and a piece of white bread with butter already spread on it.

Then, without a word, he added a small portion of something she had not seen in years. A dessert, a piece of cake with frosting. She looked up almost to make sure he had not made a mistake, but the man only nodded toward the end of the line. It was clear that this was the standard meal for everyone. The women carried their trays to the tables and sat down in groups of six or seven.

At first, no one touched the food. They looked at each other, then at the guards standing by the door. One of the older women whispered that maybe they should wait for permission, but a guard noticed the hesitation and simply said, “Go ahead, eat.” The tone was casual, not unkind.

Slowly, one by one, they began to eat. Lizel cut a small piece of the meat and tasted it. It was soft, cooked evenly, and warm all the way through. The potatoes were creamy and smooth, and the vegetables still had flavor, not overcooked, not watery. The bread was white, soft, and slightly sweet. something she hadn’t tasted in years. She had grown up eating dark rye bread, heavy and coarse.

But this bread seemed almost too light, as if it belonged to another time. When she took a bite of the cake, she felt a kind of surprise that was difficult to describe. The sweetness was unfamiliar after years of rationing, and she found herself eating slowly, trying to make it last.

Around her, the same quiet disbelief spread through the room. Some of the women smiled, some laughed quietly, and some shook their heads as if they couldn’t quite believe what they were seeing. A few even wiped their eyes, not from sadness, but from the strange relief that came with feeling full and safe for the first time in a long while.

The tension that had filled the room since they arrived began to fade, replaced by a steady calm. The guards watched without interfering. There were no shouted orders, no rush to finish, no punishment for speaking. It was a meal, nothing more. But for the prisoners, it felt like something extraordinary.

After they finished eating, the women were told to place their trays in a bin near the door. The process was quiet and organized. Leisel followed the others, returning her tray and stepping outside into the evening air. The sun had dropped low and the camp lights were turning on.

She could hear faint music coming from one of the guard buildings, some kind of American song she didn’t recognize. Walking back to her barrack, she felt full in a way she had not felt since before the war began. Her stomach was no longer tight with hunger, and her hands had stopped shaking. It was a simple thing, a meal served in a prison camp, but it carried more comfort than she could explain.

She thought about the people back home in Germany, still struggling to find food, and the contrast made her uneasy. It didn’t seem fair that she, a prisoner, was eating better than her own family. But she also knew there was nothing she could do about it. The only thing that made sense was to stay quiet, follow the rules, and be grateful that for once there was enough.

That night, as she lay in her bunk, Leisel listened to the quiet sounds of the camp, footsteps outside, the wind against the windows, and the faint hum of a generator somewhere in the distance. For the first time since leaving Europe, she did not fall asleep hungry. The day had been long and uncertain, but the food had left her feeling steady, almost calm.

She didn’t yet know what the next days would bring. But she understood one thing clearly. Life in this camp was not going to be what she had imagined when she first heard the word captivity. In the following days, the same pattern continued. Every meal arrived on time. Always enough, always warm. The menus changed slightly.

sometimes stew instead of roast, sometimes beans or cornbread or fruit from cans. Even coffee was served, and though it was weak, it was still coffee. The women began to look forward to meal time as the one part of the day that reminded them of normal life. Conversations became more relaxed and small bits of laughter returned to the tables. The guards noticed the change, too.

They began to speak a little more freely with the prisoners, sometimes making short comments about the food or joking about the portions. There was still a strict separation between the two sides, but the sense of hostility had faded. The Americans treated the women as people to be managed, not enemies to be punished.

For Leisel, every meal reinforced a simple truth she hadn’t expected to learn in captivity. that order, food, and routine could do more to calm fear than any speech or promise. She didn’t think deeply about it or try to explain it. She simply lived it day after day, sitting at the same wooden table, holding the same metal tray, and eating the same food that continued to remind her that the war, at least for her, was truly over.

As the days passed, life in the camp began to settle into a pattern that felt steady and predictable. Each morning, the women were woken up by a bell that rang from a small tower near the main gate. Leisel usually opened her eyes a few minutes before the sound because she had already learned to expect it.

The barracks were quiet at first, filled only with the sound of feet moving on wooden floors and soft voices greeting one another. Everyone folded their blankets, straightened their beds, and made sure the room looked clean before the guards came by to inspect. Breakfast came soon after. It was served in the same dining hall where they had eaten their first meal.

The food was simple but warm, usually scrambled eggs, bread, and coffee. Some mornings there was oatmeal or fruit from a tin. And once in a while the cooks served something new, like pancakes, which none of the women had ever eaten before. At first they were shy about it, unsure how to eat something so soft and sweet in the morning. But it soon became a small highlight of the day.

The food never tasted fancy, but it was consistent. and that regularity made it feel safe. After breakfast, the women were divided into small work groups. The American officers explained that the work was voluntary, but those who joined would receive small privileges, extra letters home, better shoes, or more time outside.

Lizel signed up almost immediately. She was assigned to help in the kitchen where she worked alongside both German and Italian prisoners under the supervision of American cooks. Her job was mostly cleaning and preparing vegetables, but she preferred it over sitting in the barracks all day.

The kitchen was busy from morning to afternoon, and the routine never really changed. There were big metal pots boiling water, knives chopping onions, and trays stacked in neat rows. The work was tiring, but the atmosphere was calm. The Americans gave clear instructions and rarely raised their voices. Lizel noticed how organized everything was.

The ingredients were measured carefully, the equipment cleaned after every use, and even waste was sorted neatly. It was a system that worked without confusion or chaos, and she quietly admired that. Over time, she began to talk more with the others in the kitchen. Most of them were young like her, and they shared bits of their stories while they worked.

Some had been captured in France, others in North Africa, and a few from hospitals in Italy. They all carried the same uncertainty about their families back home. The Americans allowed them to send letters once a month, but replies came slowly and many went unanswered. The waiting made everyone restless, but the work helped distract them. By the second month, the guards began to recognize her by name.

One of them, a tall man from Ohio, often greeted her when she carried supplies from the storage room. He didn’t speak German, but he always said good morning with a friendly tone, and she learned to reply with a soft good morning of her own. It was a small exchange, but it meant more than either of them probably realized.

In the camp, politeness felt like a piece of normal life that had survived the war. Evenings were the quietest part of the day. After dinner, the women were allowed to walk around the yard within the fence. Some wrote letters at the tables near the barracks. Others washed clothes or simply sat and talked. Leisel often joined a small group that gathered near the fence to watch the sunset.

From there they could see the fields beyond the camp. Long stretches of open land dotted with farmhouses and trees. The sight made her think of home, of the countryside outside Stoutgart, though she tried not to dwell on it for too long. Thinking about home only made the waiting harder.

Inside the barracks, the women started to build small routines to make life feel less like imprisonment. They shared small items, hair brushes, thread, and bits of fabric. One woman, who had worked as a teacher before the war began, giving English lessons using words she remembered from old school books. The Americans didn’t mind as long as it kept the women busy.

Lizel wasn’t very good at learning new languages. But she liked listening to the lessons, mostly for the sound of laughter that sometimes filled the room when someone mispronounced a word. Working in the kitchen also brought her small advantages.

Sometimes there were leftovers, and the cooks allowed the helpers to take small portions back to the barracks. A piece of fruit, a slice of bread, or a bit of jam became something to share quietly at night. These moments, though small, helped build a sense of community among the prisoners. They were no longer strangers forced together by war.

They had become a kind of temporary family, connected by the same walls and routines. Weeks turned into months, and the fear that had followed Lizel since her capture slowly faded. She still missed her family and worried about what was happening in Germany. But she had learned how to live with uncertainty.

The camp was not home, but it was stable, and that stability was something rare after years of chaos. Sometimes she thought about how strange it was to feel safer in a place surrounded by fences than she had in her own country during the last months of the war. But she didn’t try to understand it too deeply. Life had narrowed down to simple things, meals, work, rest, and waiting.

Each day passed quietly, and in that quiet, she began to regain a sense of normal rhythm. something she thought she had lost forever. By early spring, the air around the camp began to change. It wasn’t the weather, though the days were getting warmer. It was the way people spoke, the way they moved, and the quiet tension that ran through every conversation.

For months, the women had lived in a routine that rarely shifted. But now, small pieces of news began to filter in through the guards and Red Cross workers. The war in Europe, they said, was coming to an end. No one knew exactly when or how, but everyone could feel that something was about to change. Mail deliveries, which had always been slow and uncertain, suddenly became more frequent.

The camp office posted lists of names whenever new letters arrived, and each time the list went up, the women rushed to read it. Most names weren’t there, but a few lucky ones were called to the office to collect their envelopes. Lisel checked the lists every time, her heart tightening a little when she didn’t see her name. It took weeks before she finally received one.

The envelope was thin, creased, and stamped with a red cross mark. Inside was a single page written in her mother’s careful handwriting. Her mother wrote that their town near Stoutgard had been heavily damaged by bombing, but that she and Lisel’s younger brother were still alive.

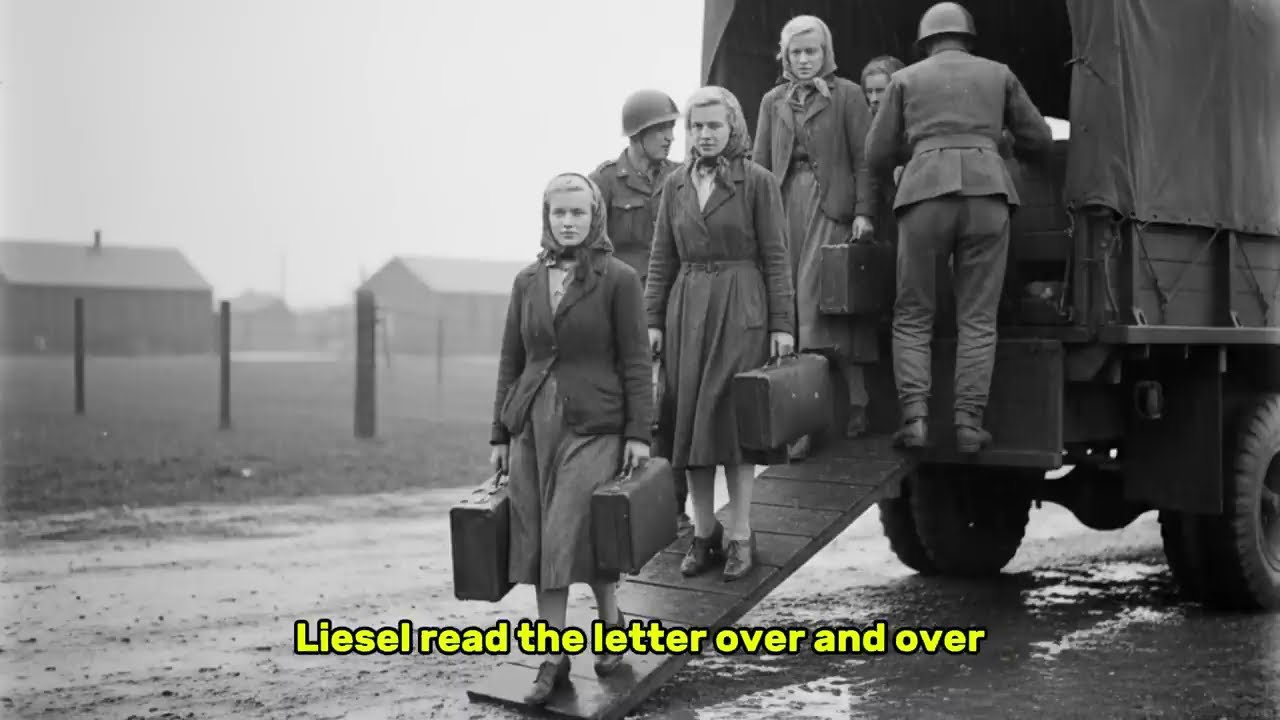

Food was scarce, and people waited in long lines for bread that ran out before everyone was served. She didn’t know what had happened to many relatives, but she ended the letter with one short line that stayed in Lizel’s mind for days. At least you are safe, even if far away. Lizel read the letter over and over until she knew every word by memory. It gave her relief and guilt at the same time.

Relief because her family had survived. Guilt because she ate three full meals a day while they struggled to find enough. She didn’t talk much about it, but she noticed that the other women felt the same. When letters came, they brought both comfort and pain. Some cried quietly, others stared at the paper without speaking.

Those who received no mail at all seemed to grow quieter with each passing week. The Americans never shared official news with the prisoners, but information spread anyway. Some guards hinted that Berlin was surrounded. Others mentioned that the German army was collapsing. A few prisoners who worked near the offices overheard radio reports.

The details were never clear, but the direction of the war was obvious. Every rumor carried both hope and fear. Hope that the fighting would stop. Fear of what the end might mean for the people back home. Lisel kept working in the kitchen, but the mood had changed there, too.

The American cooks seemed lighter, sometimes even cheerful, while the German helpers grew more withdrawn. No one said it openly, but everyone understood that Germany was losing. During breaks, women whispered about what would happen if the war truly ended. Would they be sent home immediately or would they stay as prisoners until arrangements were made.

No one knew, and the Americans didn’t answer questions about it. One afternoon near the end of April, an officer entered the kitchen carrying a newspaper. He handed it to one of the cooks who read the headline and nodded slightly.

The officer said something quickly in English, and though Leisel couldn’t understand all the words, she caught one clearly. surrender. The sound of it made her stop working for a moment. She looked at the others, but no one spoke. The officer folded the newspaper and left the room. The Americans didn’t celebrate loudly, but the difference in their mood was clear.

The war in Europe was over, or almost over, and everything they had known up to that point was now part of the past. That evening, the guards didn’t follow their usual schedule. The women were allowed to stay outside longer than usual. And though no one explained why, everyone knew the reason. Some prisoners stood near the fence and stared out at the horizon in silence.

Others gathered in small groups, trying to understand what peace meant for them. Now Leisel sat on a bench near the barracks, holding her mother’s letter in her hands. She wanted to feel happiness that the war had ended, but she couldn’t. The word peace felt too heavy, too complicated for her. Nothing had really changed yet. She was still behind a fence, still far from home, and still uncertain about what came next.

Over the next few weeks, more letters arrived. Some confirmed that Germany had surrendered. Others described the chaos that followed. Towns in ruins, soldiers returning home to nothing, families searching for one another. The women read these letters together, sharing bits of information and trying to imagine what their country looked like now.

The idea of returning home no longer felt simple or even entirely hopeful. There was relief, but also fear of what they would find when they got there. Life in the camp continued much the same way for a while. The guards were more relaxed, and the work went on as usual. But something had shifted permanently. The women no longer felt like prisoners of war, waiting for orders.

They were displaced people waiting for a world to rebuild itself. Every day felt longer, filled with a quiet kind of waiting that had no clear end. Lizel kept her letter folded neatly in her locker, reading it on quiet nights when the camp lights dimmed. It reminded her that somewhere beyond the fences, her family was still alive and that eventually she would see them again.

She didn’t know when or how, but that small belief was enough to keep her steady through the uncertain months that followed. It took many months after the end of the war before Lazil and the other women were told they would finally be sent back to Germany. The camp staff didn’t give them a specific date at first, only saying that arrangements were being made and that transportation would take time.

Ships were limited, papers had to be approved, and many countries were still sorting out what to do with thousands of prisoners scattered across the world. The waiting felt endless. During those months, the daily routine continued almost exactly as before. The women still worked in the kitchen, cleaned their barracks, and lined up for roll call.

The only difference was the tone of everything around them. The guards no longer seemed watchful in the same way. Some even spoke more openly, asking questions about Germany, about family, about home. A few prisoners were trusted with small jobs outside the fence, working in nearby fields or repairing buildings, always under supervision, but with far more freedom than before.

Then one morning in early autumn, a list was posted on the main board. It was longer than usual, and at the top were the words, “Return transport group one.” Leisel’s name was on it. She read it twice to be sure, and when she turned around, she saw other women reacting the same way. Relief, excitement, and worry all mixed together.

For months, they had spoken about this moment. But when it finally came, it didn’t feel entirely real. They didn’t cheer or celebrate. They just stood quietly, reading their names again, trying to understand that their time behind the fences was truly ending. In the days that followed, they were given new clothes and told to pack the few belongings they had collected.

Most of it fit into small cloth bags, letters, photographs, and bits of clothing they had mended over the months. The camp officers explained the route they would take. First by train to the east coast, then by ship across the Atlantic, and finally through temporary processing stations in Europe before reaching Germany.

No one knew what they would find when they arrived, but everyone knew it would not be the same country they had left. When the trucks came to take them away, the Americans lined up to check their names one last time. Some of the guards who had been in the camp for months shook hands with the prisoners or simply nodded goodbye.

There was no ceremony, no music, just a quiet sense of ending. Lizel climbed into the back of one of the trucks and looked at the camp for the last time. The fences, the towers, and the dining hall, where everything had first seemed so strange. It had been a prison, but it had also been a place of safety and structure, and leaving it brought a strange mix of freedom and fear.

The train ride to the coast took several days. The scenery outside the windows passed by in long stretches of open land, towns, and rivers. Many of the women pressed their faces to the glass, taking in as much as they could. The America they had seen only through fences now seemed wider and calmer than they had imagined.

They talked quietly among themselves about the food, the order, and the strange politeness of their captives. Lizel didn’t say much, but she listened. She thought about the first meal she had eaten in the camp, the mashed potatoes, the roast beef, the soft bread, and how something as simple as a plate of food had changed the way she saw her enemies.

At the port, the women were loaded onto a large ship along with hundreds of other returning prisoners. The American officers gave final instructions, checked the lists again, and wished them safe travel. When the ship pulled away from the dock, many of the women stood at the railing, watching the shoreline fade. Some cried, some stayed silent. Liil didn’t cry.

She felt something deeper, a quiet heaviness that came from knowing she was leaving behind the only stable place she had known in years, heading toward a future she couldn’t imagine. The journey across the Atlantic was long but calm. The women were given regular meals and kept in separate quarters from the male prisoners.

They spent most of their time talking, reading old letters, or staring at the water. Every day felt slower than the one before. As they neared Europe, the conversations grew quieter. No one knew what they would find when they arrived. Families gone, homes destroyed, cities in ruins. Yet, everyone wanted to see it with their own eyes, no matter how bad it might be.

When the ship finally docked, the passengers were met by Allied officers and Red Cross workers. The air was cold and the harbor was crowded with people returning from every direction. Leisel followed the group through checkpoints and processing tents, moving slowly through lines that seemed to go on forever.

The officers gave them basic instructions, a small ration of food and papers that would allow them to travel to their home regions. After that, the group was dismissed. For the first time in years, Lizel stood outside a fence with no guard watching her. She didn’t know where to go first, but she started walking toward the train station with a few others from her camp.

The tracks would take her east toward what was left of Stoutgart. She didn’t know if her family was still there or if the house had survived, but she needed to find out as the train moved through the ruined countryside. She saw the destruction for the first time.

Towns flattened, bridges broken, smoke still rising from distant buildings. It was not the Germany she remembered. Yet despite the shock, she kept looking out the window, determined to see it all. The fences, the uniforms, the camp routines, all of it was behind her now. The war had ended, but rebuilding her life was only beginning.

When she finally stepped off the train days later, the streets were quiet and nearly unrecognizable. Buildings she had known were gone, replaced by piles of stone. But somewhere beyond the rubble, she hoped her family was waiting. Holding her small bag close, she walked slowly toward what used to be her neighborhood, ready to face whatever she found there.

When she finally stepped off the train days later, the streets were quiet and nearly unrecognizable. Buildings she had known were gone, replaced by piles of stone. But somewhere beyond the rubble she hoped her family was waiting.

Holding her small bag close, she walked slowly toward what used to be her neighborhood, ready to face whatever she found there. When Lizel finally reached the outskirts of her hometown, she hardly recognized it. The train station was still standing, but much of the area around it was blackened and broken. Streets she had known since childhood were buried under piles of bricks.

People walked slowly through the debris, carrying buckets, shovels, and small bundles of belongings. No one moved quickly, and no one spoke loudly. The war had ended, but its shadow still hung over everything. She followed what was left of the main road toward the neighborhood where her family had lived.

The houses were half destroyed, their roofs missing, their walls scorched. She passed a group of children digging through rubble for bits of wood and an old man sitting on a doorstep staring at a cracked photograph. Every few steps, she stopped to look around, trying to see something familiar. It was difficult to tell where one house ended and another began.

When she reached the spot where her home had once stood, she saw only the remains of the foundation and part of a wall still upright. The sight made her stand still for a long time. She didn’t cry, but she felt the air leave her lungs. There was a small garden behind the ruins, overgrown and scattered with stones.

But the fence her father had built years ago was still there, bent, but recognizable. For a moment, that small detail was enough to keep her standing. A neighbor appeared from a nearby building, a woman she remembered faintly from before the war. The woman recognized her immediately and hurried over.

She told Leisel that her mother and brother had survived and were living in a temporary shelter on the other side of town. They had been forced to move after a bombing, but they were alive. The words came quickly, and before Leisel could even respond, she found herself walking again, this time with a clear direction. The shelter was a converted school building, crowded and noisy.

Families shared classrooms and every hallway smelled of smoke and soup. When Leisel entered, she saw her mother sitting on a wooden bench near the wall. For a moment, they both just looked at each other, unable to move. Then her mother stood, and the two of them finally embraced. Her younger brother came running a moment later, his face thin but bright with recognition.

They didn’t speak right away because there was too much to say and too little space to fit it all. In the days that followed, Leisel learned what had happened during the years she’d been gone. Her father had died during an air raid, and her mother had worked in a factory until it closed.

Food was still rationed, but at least there were distribution points, and aid was beginning to arrive from the Allies. Everything was about rebuilding. One wall, one road, one life at a time. Leisel didn’t tell many stories about the camp. When people asked where she had been, she simply said, “In America.” Some neighbors looked surprised, others suspicious, but she didn’t explain further.

How could she describe the strange safety of that place, the regular meals, the clean beds, the guards, who treated her better than her own government had in the final months of the war? It was easier not to explain at all. She spent her days helping her mother gather supplies and cleaning what was left of their old house.

Each morning, she joined other towns people clearing rubble from the streets. Everyone worked quietly side by side. There was no anger left, only exhaustion and the slow, heavy work of rebuilding. At night, when the lights went out early to save power, Leisel sometimes thought back to the camp’s dining hall, the smell of bread, and the order that had kept her life steady.

It wasn’t nostalgia, just memory. The war had taken away too much to leave space for longing. But she understood something simple now. That survival didn’t always come from victory or pride, but from structure, food, and the small routines that kept people moving forward when everything else was gone. The weeks turned into months, and the ruins around her slowly changed shape.

New roofs appeared. Shops reopened. People began talking about the future again. Lizel didn’t know what that future would bring, but she had learned how to live one day at a time. The fences of the camp were gone, but the lessons she had carried from behind them stayed with her, quiet, steady, and unspoken.

News

GOOD NEWS FROM GREG GUTFELD: After Weeks of Silence, Greg Gutfeld Has Finally Returned With a Message That’s as Raw as It Is Powerful. Fox News Host Revealed That His Treatment Has Been Completed Successfully.

A JOURNEY OF SILENCE, STRUGGLE, AND A RETURN THAT SHOOK AMERICA For weeks, questions circled endlessly across social media, newsrooms,…

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own The year was 1883,…

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist…

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart “Get your filthy hands…

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how.

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how. “Is this a joke?” barked…

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist….

End of content

No more pages to load