German “Comfort Girl” POWs Couldn’t Believe Their First Sight of America

Her name was Elizabeth. She was only 23 years old, and she had worked near a German supply camp, mainly doing laundry and clerical tasks for soldiers. She was not a combatant, and she had never imagined that she would become a prisoner of war. Near the end of 1944, when Allied forces swept through the region faster than anyone expected, she and several other women were gathered by soldiers and questioned.

They were told that because they had worked for the German military, the idea felt unreal to Elizabeth because she had grown up in a small town and had expected to return home after the war ended. Instead, she was placed on a truck headed toward the coast. She carried only a small bag with basics, a hairbrush, a comb, and one extra shirt. She did not know where she was being taken, only that the journey would be long.

But before we continue, I want to clarify that this is a story I discovered in the World War II archives. And if you want to hear more untold stories from history, make sure to like the video and hit the subscribe button and tell me in the comments what country you’re watching from. It’s really fascinating to see how far these forgotten stories can reach. All right.

When the truck reached the harbor, Elizabeth saw the ship waiting. It was large and crowded with uniformed guards and prisoners, men and women, all being loaded into different sections. Seeing the ocean unsettled her, it felt like a border between her old life and a future she could not picture.

Days at sea passed slowly. Meals were simple, but she noticed the guards were not hostile toward them. They gave instructions without shouting. Sometimes when language got in the way, a guard tried to explain something by pointing or using hand gestures. Elizabeth realized that these men did not act like the enemies she had been told to fear.

They were simply doing their duty, just as she once had. Rumors spread that the ship was not headed to England or France. It was going all the way to America. Elizabeth listened but refused to believe it at first. America felt too far away to be real. Some women whispered that America had plenty of food, that there was no hunger.

Elizabeth wanted to hope, but fear kept her from embracing the idea. When the ship finally slowed down, a voice called out that land was ahead. Every prisoner, including Elizabeth, moved toward the railings. Some climbed onto crates just to see over others. Elizabeth squeezed between two women and looked out.

She had expected a coast that looked similar to what she knew from Europe, possibly damaged, crowded with soldiers, tense, and chaotic because of the war. Instead, she saw a port that looked organized and busy, and nothing about it suggested a nation living under bombing or fear. Elizabeth could see large cranes moving cargo from ships.

Workers operated machines with a steady pace, not in panic or exhaustion. Trucks lined up to collect materials. People on the docks worked without looking over their shoulders or reacting to distant explosions. Everyone looked focused on tasks, and nobody seemed worried about safety. It was a normal workday to them, even though a ship carrying prisoners of war had just arrived. She tried to take everything in at once.

Cloth banners labeled different warehouses. Guard posts were present, but the guards near the docks behaved casually. They leaned on railings, talked among themselves, and occasionally pointed toward the ship to direct workers on where to position the gang way. They were not tense. They were not shouting. They were not rushing.

Elizabeth realized what she was seeing. This place had routine. Routine meant the war did not reach their daily lives. The idea felt difficult for her to process. She had spent years waking up to air raid sirens, rushing to shelters, and walking past damaged buildings on her way to work. She expected any military area to resemble the crowded and anxious atmosphere she had known in Germany.

Everything looked controlled, predictable, and stable. A guard spoke to the group of women through a translator. They would disembark soon, and they would be taken through processing. The tone wasformational rather than commanding. Elizabeth listened closely. She did not want to miss any instructions.

She felt her stomach tighten when she heard that they were officially in the United States. Even though she had suspected it during the voyage, hearing it confirmed made the situation more real, she was farther from home than she had ever imagined she could be.

As the ship docked, she noticed the cleanliness of the work areas. There was no trash piled in corners, no broken equipment, no signs of neglect. Everything had a place. Workers cleaned equipment after use. People wore uniforms that looked new, not patched or repaired. In Germany, especially near the end of the war, equipment was used until it fell apart.

Here, nothing appeared worn out or near failure. Elizabeth observed the vehicles on the dock. They were large and moved without stalling. She had heard months earlier that America had an endless supply of fuel. But seeing vehicles moving without hesitation made her understand the difference. It was not just abundance of fuel. It was stability.

Stability shaped how people behaved, how they worked, and even how they moved. The moment she stepped onto the gang way, she felt the solid surface under her boots. She felt watched, but not threatened. Guards stood nearby, but they kept a professional distance. They did not push or rush the prisoners. They just directed them where to walk.

Elizabeth followed the path with the others. For the first time in a long while, she was in a place not dominated by war damage. It made her feel small, uncertain, and strangely relieved at the same time. She could not stop thinking one thing. They have no idea what the war feels like the way we do.

When Elizabeth and the other women reached the camp, the guards directed them into a long building. Everything happened in a steady order. There was no shouting or confusion. The women were separated into lines, and each line moved toward a table where American personnel waited with papers, typewriters, and folders. Elizabeth looked around carefully. She wanted to understand what would happen next.

She noticed that the camp staff behaved as if they had done this process many times before. They did not rush, and they did not seem angry or stressed. Their behavior gave her a small sense of safety, even though she was still afraid of what the future might hold. When it was her turn, an officer asked for her name. He spoke slowly, knowing that not all prisoners understood English.

A German-speaking interpreter repeated the question for her. Elizabeth said her name, and the officer typed it into a form. The typewriter keys clicked rapidly. Each strike sounded final, like a stamp sealing her identity inside a system she could not control.

She was asked her age, birthplace, and previous occupation. The interpreter repeated each question. Elizabeth answered honestly because she did not see any benefit in lying. She could tell that they were collecting information, not trying to intimidate her. After the interview, she was directed to another table where she was issued a small identification tag.

It had a number printed on it. The officer explained that the number was now linked to her file and that she would use it when receiving supplies, meals, or work assignments. Elizabeth did not like the idea of being a number, but she understood that the process was not personal. It was simply their system.

Next, she was given a camp uniform, durable trousers, a shirt, and a jacket. The fabric was rough but clean. She was also given bedding that consisted of blankets and a pillow. The guard handed everything to her without comment. Elizabeth was surprised by the cleanliness of the items. She remembered the shortages back home where every scrap of cloth was reused, patched, or cut apart. Here, everything seemed available and maintained.

The guards led the women to a room where they could wash and change into the uniforms. For the first time in days, Elizabeth used running water. She washed her face and hands slowly because she did not know when she might have access to clean water again. The uniform fit loosely, but it was comfortable enough.

When she folded her old clothing, she felt a sharp sense of separation from her past. The uniform meant she was no longer just Elizabeth. She was a prisoner in a foreign country. After changing, the women were led to the dining hall. There, Elizabeth received her first camp meal.

She watched as staff placed food on trays in an organized and consistent manner. No one grabbed or pushed. No one yelled. When her turn came, she received soft white bread, a pat of butter, jam, warm vegetables, and potatoes. When she sat down and took the first bite, she had to pause. She had not tasted bread like that in years. In Germany, food had become dry, rationed, flavorless, stretched as far as possible to feed many people with little supplies. here.

Everything tasted fresh. It startled her that something as ordinary as bread could affect her so strongly. She looked around the room. The other women were having similar reactions. Some ate slowly, afraid of appearing greedy. Others wiped away tears quietly because the taste of real food reminded them of life before the war.

A guard stood near the entrance watching, but he kept a respectful distance. It was clear his job was to supervise, not to interfere. After the meal, the prisoners were led outside to their assigned barracks. The building was plain and functional. Inside were rows of bunk beds, a small heating unit, and space for personal items. Each woman chose a bed.

Elizabeth placed her bedding on the mattress and smoothed it out. She sat down and exhaled for what felt like the first time that entire day. The room was quiet. No alarms, no distant explosions, just the sound of women settling into unfamiliar yet safe surroundings. That night, she lay awake, listening to the steady breathing of the other prisoners.

She did not feel free, but she felt something else, something she had not felt during the final months in Germany. She felt that tomorrow would follow a schedule. She would eat, she would work, she would sleep. The war could not interrupt these things here. The structure of the camp gave her something she had lost, predictability.

In the days that followed, Elizabeth began to understand the daily structure of the camp. Everything ran according to a fixed schedule which was posted on a board outside the barracks. Wake up time, breakfast, work assignments, breaks, evening hours. It was all laid out clearly. The guards did not allow anyone to ignore the rules, but they did not treat the women harshly either.

Orders were delivered in short statements. Gestures helped bridge gaps in language. The structure allowed the prisoners to know what to expect each day, and that stability slowly eased the constant tension inside Elizabeth’s stomach. Work assignments varied from person to person.

Some women sorted laundry, washed dishes, or cooked in the kitchen under supervision. Others were taken outside the camp to help with agricultural work, such as picking vegetables or sorting crops on nearby farms. The guards walked alongside them during transport, but they did not shout.

Elizabeth had been assigned to the sewing room because she knew how to mend clothing. The room was set up with tables, sewing machines, and baskets of fabric. Elizabeth and a small group of women repaired uniforms and clothing for camp personnel. It was repetitive work, but she found comfort in the familiarity of the task.

Threading needles and following seams gave her something she could control. During her first week of work, Elizabeth noticed something that surprised her. Sometimes a guard would hold up a torn sleeve or jacket and ask her through the interpreter if she thought it was repairable. The guard was not testing her. He genuinely relied on her judgment.

For the first time since the capture, she felt that her skills mattered. She was still a prisoner, of course, but her abilities gave her a sense of purpose and routine. Meals were served three times a day in the dining hall. They were simple but consistent. Potatoes, vegetables, bread, occasionally meat. The portions were reasonable, not small or watered down. She could finish her meals without feeling watched or rushed.

After years of rationing and shortages back home, the dependability of food alone felt like something remarkable. No scrambling, no fear that the supply would run out. In the evenings after work and dinner, the women were free to spend a few hours inside the barracks or outside in a small recreational yard within the fence. Some played cards, others read or wrote letters. Elizabeth often sat on her bunk and cleaned her uniform or organized her bedding.

It allowed her to feel grounded in a foreign place where everything was unfamiliar. Over time, she noticed small details that showed how different life here was compared to wartime Germany. Tools were not locked away. Supplies were not rationed. If something broke in the sewing room, a replacement was provided.

If the guards told prisoners to line up, they did so without panic. No one ran for shelter because there were no explosions or sirens. The camp had rules, but it also had predictability. Predictability slowly replaced fear. The women formed small friendships within the camp, mostly based on work groups or shared barracks.

Conversations were quiet and cautious at first, focused on daily tasks or memories from home. They avoided talking about the future because the future was uncertain. Elizabeth did not know when she would return to Germany. She did not know what would be left when she did, but she knew she would sleep in the same bed each night, eat at the same time each day, and work in a warm room with steady lighting and functioning tools.

As weeks passed, Elizabeth began to notice something that surprised her again and again. The food in the camp was not only regular, it was varied. In Germany, especially near the end of the war, meals had become predictable and scarce. Bread was dark and stretched with fillers. Butter was replaced with substitutes.

Vegetables were stored for too long or boiled until flavor disappeared. Here in the United States, even basic meals tasted different. Once a week, the camp kitchen received ingredients that Elizabeth had not seen in years. Sometimes it was peanut butter, something she remembered only from stories about America. It came in large containers and had a thick texture. It stuck to the roof of her mouth at first and she did not know what to think of it.

But eventually she learned to spread it on bread and eat it slowly. The taste was unfamiliar but rich and she realized it was full of calories. In Germany, anything that could give energy had become valuable. Here it was just another option on the table. Another time she received cornbread with her meal.

The texture was dense and slightly crumbly and the flavor was mildly sweet. She had never eaten anything made from cornmeal before. In Germany, corn was mostly animal feed, not something used to make bread. She studied the piece on her tray at first, confused about whether it was dessert or bread. When she bit into it, she was surprised by the balance of sweet and savory flavor.

The women at her table exchanged comments, trying to decide if they liked it. Elizabeth did. It felt warm and filling. There were days when the kitchen served stew with beans, carrots, and pieces of meat. The broth was thick, and the dish could keep a person full for hours. Elizabeth noticed that many American meals focused on protein and energy, not just taste.

It was practical food made to support long work days. She respected that it was different from German meals, which often focused on sauces, potatoes, and familiar spices. American food seemed simpler, heavier, and built for function. Occasionally, the guards allowed leftover baked goods from the staff kitchen to be placed on the prisoner serving line.

Elizabeth remembered one day in particular when a tray of muffins appeared. They were slightly sweet, and some had pieces of dried fruit inside. The women stared at them as if they were fragile. Elizabeth held hers carefully. It felt wrong to take something that looked expensive, something that felt like a treat.

She ate it slowly, feeling each bite as a reminder that there were still normal moments in the world. During certain weeks, the prisoners received fresh fruit, one piece per person. Apples were the most common. They were firm with crisp texture.

In Germany, near the end of the war, a single apple might have been shared among several people in a household. Here, it was given without hesitation. The simple act of biting into fresh fruit without concern about rationing felt unreal to Elizabeth. She noticed she always ate the fruit last during meals, saving it as a reward. Over time, Elizabeth realized that the food affected more than hunger. It affected mood. People became calmer.

Conversations during meals grew longer. Some women opened up about their families, their homes, and memories from before the war. Elizabeth listened to these stories while eating food that reminded her that the world still had normal places in it.

The camp still controlled her movement, but the availability of food gave her back a sense of dignity. Over the weeks, Elizabeth began to notice patterns in how the American guards behaved. At first, she had expected them to be harsh, strict, or even cruel based on everything she had heard about enemy soldiers. Instead, most of them were professional, polite, and consistent in their instructions.

They spoke clearly, used gestures when words failed, and rarely raised their voices. Elizabeth noticed that their role was to supervise, not to intimidate or punish unnecessarily. It created a strange mix of tension and comfort. She was still a prisoner, but the guards were not actively trying to make her life miserable. Some guards showed small acts of fairness or thoughtfulness.

If a prisoner dropped a tool or piece of equipment while working, a guard would hand it back without comment. If someone had trouble carrying a heavy load, the guard might nod and wait patiently until the prisoner caught up. These gestures seemed small, but for Elizabeth, they were meaningful. They showed her that the guards were not cruel by nature.

They were performing a duty within rules and structure. She began to feel that the environment, though confined, was predictable and reliable. Communication was still a challenge. Elizabeth’s English was limited, and only a few guards spoke German. Interpreters were available, but not always present. Still, Elizabeth found that simple gestures, nods, and written notes could help.

Over time, she learned which guards were patient and which were strict. She adjusted her behavior accordingly, following instructions promptly and showing effort in her work. She realized that respect could go both ways. By behaving responsibly, she received more freedom and trust. Sometimes guards interacted in casual ways.

They asked simple questions about the prisoners well-being or where they were from. Elizabeth noticed that these small exchanges made a difference in morale. Even though she could not speak freely about Germany or the war, acknowledging that someone cared about her safety or comfort gave her a sense of humanity.

It was different from life during the final months in Germany where fear and scarcity dominated interactions. Physical contact was limited and formal. Guards did not hit, push, or force prisoners unnecessarily. Discipline was administered according to strict rules. Elizabeth observed that violations of the camp’s regulations were handled calmly and methodically. A warning was given first.

If the warning was ignored, a small punishment might follow, such as extra work hours or temporary restriction from certain areas. Even these punishments were not violent or excessive. They were measured, and Elizabeth could predict the consequences if rules were broken. Over time, Elizabeth began to see the guards not as enemies, but as people performing a difficult job in a foreign country.

She never forgot that they were armed and in control of her life. But she also saw that their responsibility required order and fairness. Their presence became part of the routine she had grown accustomed to. Another predictable element in her daily life. She felt that following instructions and showing respect allowed her to live with fewer conflicts and more personal space.

Elizabeth also learned small lessons about trust. She could ask a guard for clarification if she did not understand a task. She could rely on them to provide equipment or maintain safety during work. Though the camp remained a prison, the guard’s behavior allowed her to adapt to the environment without constant fear.

Over time, she realized that human interactions, even under strict circumstances, could include fairness, patience, and reliability. By the end of her first month in the camp, Elizabeth felt a cautious respect for the guards. She understood her place as a prisoner, but she also understood that the men in uniform were not monsters. They were professionals following rules.

And in doing so, they gave her and the other prisoners a structure that made life inside the camp manageable and predictable. After a few weeks in the camp, Elizabeth received her first opportunity to write a letter home. It was a small piece of paper and the pens were simple, but the chance to communicate with her family filled her with hope and anxiety at the same time.

She carefully wrote her name, date, and a few words about her health and daily life. She avoided mentioning anything political or about the war. She simply wanted to let her family know that she was alive. Holding the envelope in her hands, she felt both relief and fear. Would her letter reach Germany? Would her family even be able to read it? Receiving replies was even more complicated. Letters arrived weeks later, sometimes incomplete or delayed.

When Elizabeth finally received a letter from her mother, she could barely believe it. Her handwriting on the page was messy and hurried, but the words were clear. Her family was alive, though tired and living in difficult conditions. Elizabeth clutched the letter, reading it again and again, finding comfort in every line.

Even though she was far from home, those small notes reminded her that she had connections that survived the war. News from Germany traveled slowly through letters and occasional camp bulletins. Elizabeth learned about shortages destroyed homes and cities under bombing campaigns. It was difficult to read, but it helped her understand that her life in the camp, although restrictive, was safer than what many people at home were facing. Sometimes the news felt heavy, but she tried to balance it with memories of better times.

She thought of her parents, her small hometown, and the streets she had walked before the war. The letters were a bridge between two worlds, one familiar and one entirely new. Writing letters also gave Elizabeth a sense of agency.

Even if she could not influence the outcome of the war or the choices made by others, she could choose her words carefully, report on her health, and maintain a connection with home. These letters became part of her daily routine. She would sit at a small table in the barracks, organize her thoughts, and write slowly. The process required patience.

She often revised sentences to make sure they were clear and would not worry her family unnecessarily. Sometimes other women in the camp would gather to exchange news about letters. They would share when letters had arrived, what they said, or what parts of home had changed. Elizabeth found some comfort in these conversations.

Hearing others describe news from their families reminded her that she was not alone in her feelings of worry, relief, and hope. It created a quiet sense of community among the prisoners, something she had not expected when she first arrived. Through the weeks, the letters also helped Elizabeth maintain perspective. She understood that she was living in a controlled environment where safety, food, and shelter were predictable.

Even though she longed for home, she could see that the camp offered protection from the chaos happening in Germany. Each letter she wrote or received reinforced this balance. The outside world was dangerous and uncertain, but inside the camp, she had stability. Eventually, Elizabeth learned to look forward to mail days.

She could not predict what she would receive, but even small scraps of news, a few words from her parents, or a brief note from a friend gave her hope. The letters became more than communication. They were reminders of the life she would eventually return to, the world waiting beyond the fences, and the reason to endure the routine, the work, and the time in the camp.

German prisoners of war held in the United States were part of a highly organized system designed to manage large numbers of captives far from the battlefields of Europe. Camps were constructed with clear rules, schedules, and designated work assignments. Prisoners were expected to wake, eat, work, and sleep according to strict routines.

Although the camps were safe and the guards generally treated prisoners fairly, life was not easy. The work could be physically demanding and prisoners had very limited freedom. Most men and women were assigned to labor in kitchens, laundry, workshops or agricultural fields.

These tasks were essential for the operation of the camp and failure to complete assignments could lead to warnings or small punishments such as extra work hours or temporary restrictions. Food was more abundant than what prisoners had experienced during the war, but it was still rationed and served in strict portions.

Meals were consistent and carefully planned to provide enough calories for daily work. Despite the relative abundance, prisoners had no control over what they ate or when, and they had to adjust to unfamiliar American foods. Living quarters were shared, often crowded, and privacy was minimal. The combination of labor rules and limited personal space made life monotonous and challenging, even when the basic needs of food and shelter were met.

As the war in Europe ended in 1945, the situation for German PSWs began to change. The United States prepared to repatriate prisoners. But the process took time because of the sheer number of captives and the complexity of transport logistics. Prisoners were organized into groups and placed on ships bound for Europe. Many camps continued to operate for weeks or months after Germany’s surrender, maintaining routines and work assignments until departures were arranged. Once returned to Germany, prisoners faced a new set of challenges.

Much of the country had been damaged by bombings, infrastructure was disrupted, and basic resources like food, housing, and medical care was scarce. Former prisoners often had to rebuild their lives from scratch. While the American camp system had kept them alive and generally safe, it could not prepare them for the social, economic, and emotional difficulties that awaited in postwar Germany.

Overall, the American P system achieved its primary goals. It kept prisoners secure, organized, and fed until they could be returned home. Life in the camps was regimented and demanding with limited personal freedom, but it was far safer than the conditions in Europe during the last years of the war.

The system required prisoners to adapt to strict routines, perform necessary labor, and accept a high level of oversight. By the time repatriation occurred, the prisoners had endured months of controlled, disciplined life far from their homes, and they returned to Germany physically safe, but facing the immense challenge of rebuilding their lives in a wartorrn country.

The system of German prisoner of war camps in the United States left a lasting impact on both the prisoners and the country that hosted them. For the prisoners, the camps provided safety, reliable food, and medical care, which had often been scarce or unavailable in Europe.

While life in the camps was strict and laborious, the experience introduced many prisoners to organization, order, and routines that were different from the chaos of war torn Europe. The structure and consistency helped prisoners survive physically and in some cases emotionally, although adjustment back home after repatriation remained difficult.

Many returned to Germany with new skills they had learned in the camp, such as farming techniques, cooking methods, or mechanical repair, which could be applied to rebuilding their communities. For the United States, the P camps demonstrated the ability to manage thousands of enemy combatants effectively on domestic soil.

The camps were carefully planned to balance security, labor needs, and humane treatment. Reflecting adherence to international agreements such as the Geneva Convention, American officials learned how to organize logistics for food distribution, work assignments, and medical care on a large scale, experiences that influenced postwar military planning, and administrative procedures. The camps also had economic effects.

Prisoner labor supplemented labor shortages caused by the war, especially in agriculture and manufacturing, contributing to local communities and ensuring essential production continued. The legacy of the camps extended beyond practical outcomes. They showed that even in wartime, strict security and humane treatment could coexist.

Stories from former prisoners highlighted moments of fairness, consistent routines, and acts of professionalism by guards, which contrasted sharply with the hardships and dangers they had experienced in Europe. For historians, the camps serve as a case study in balancing security, labor, and humanitarian obligations during conflict.

Although the camps no longer exist, their impact persisted. Former prisoners often remembered the stability and predictability of life in the United States with a mix of relief and reflection. The experience demonstrated the capacity of organized systems to maintain order over large populations under unusual and difficult circumstances.

The lessons learned influenced both military policy and international approaches to prisoner treatment in later conflicts. In the end, the American P camp succeeded in their main objectives. They kept prisoners alive, safe, and productive until repatriation, while also demonstrating a functioning system of rules, labor, and supervision that balanced control with basic human dignity.

The camps became a historical example of how a nation can manage large numbers of enemy combatants effectively while maintaining legal and ethical standards, and they remain a significant part of the story of World War II. As the war ended, German prisoners of war in the United States began the process of repatriation.

This process took time because of the large number of prisoners and the logistical challenges of transporting them across the Atlantic. Ships had to be organized and prisoners were grouped carefully to ensure safe travel. Even though Germany was no longer at war, returning home was not simple. Many prisoners faced destroyed cities, shortages of food and housing, and disrupted communities.

The transition from structured camp life to the uncertainty of postwar Germany was difficult, and for some, it required months to adjust physically and emotionally. Repatriation was not only a physical journey, but also a social and psychological one. Prisoners had lived under strict routines with predictable work, meals, and supervision.

Returning to a country struggling to recover meant encountering chaos and scarcity instead of the controlled environment they had become used to. Despite these challenges, former PWs often carried lessons learned in the camps, patience, discipline, and practical skills. Many used these skills to contribute to rebuilding efforts, whether in agriculture, construction, or other trades.

The American P system also left a broader historical legacy. It became an example of how a nation could treat enemy prisoners according to international standards while maintaining security and using labor effectively. Stories from former prisoners showed that structured humane treatment could reduce conflict, maintain morale, and even provide skills useful for life after the war.

Scholars studying the camps note that while life was not easy, the experience was far safer than remaining in wartime Europe. Ultimately, the repatriation of German prisoners marked the end of an unusual chapter in both American and German history. The camps had managed thousands of prisoners, maintained order, and provided basic needs. Yet, they could not erase the long-term consequences of the war itself.

For former prisoners, the journey home was both relief and challenge. A return to a homeland in need of reconstruction, where survival and adaptation continued long after the last camp gates had closed.

News

GOOD NEWS FROM GREG GUTFELD: After Weeks of Silence, Greg Gutfeld Has Finally Returned With a Message That’s as Raw as It Is Powerful. Fox News Host Revealed That His Treatment Has Been Completed Successfully.

A JOURNEY OF SILENCE, STRUGGLE, AND A RETURN THAT SHOOK AMERICA For weeks, questions circled endlessly across social media, newsrooms,…

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own The year was 1883,…

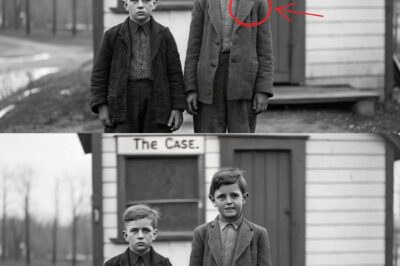

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist…

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart “Get your filthy hands…

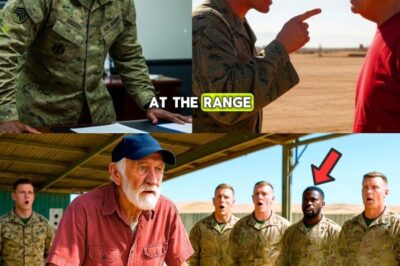

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how.

U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how. “Is this a joke?” barked…

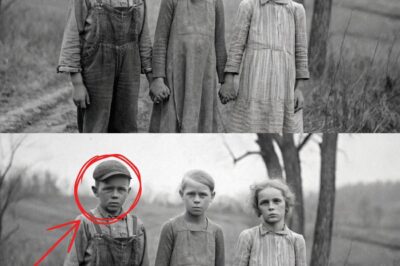

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist….

End of content

No more pages to load