After Generations of “Pure Blood,” the Heir Was Born With Someone Else’s Voice

There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist. It was taken in the summer of 1953 in a house that no longer stands in a town that doesn’t acknowledge what happened there. In the photograph, a woman holds an infant. She’s not smiling. Her eyes are fixed on something beyond the camera’s frame. Something the photographer chose not to capture.

The baby’s mouth is open, caught midcry. But according to the three people who were in that room, no sound came out. Not then, not for weeks. And when the child finally did make noise, everyone who heard it felt their skin crawl. Because the voice that came from that infant’s throat didn’t belong to a newborn.

It belonged to someone who had been dead for 27 years. This isn’t folklore. This isn’t a ghost story shared around a campfire. This is what happens when a family becomes so obsessed with purity, so consumed by the idea of keeping their bloodline untainted that they forget blood has memory. And sometimes that memory has a voice. Hello everyone.

Before we start, make sure to like and subscribe to the channel and leave a comment with where you’re from and what time you’re watching. That way, YouTube will keep showing you stories just like this one. The Witmore family arrived in Ashefield, Virginia in 1792. They came with land deeds, money, and a belief that would define them for the next 160 years. bloodline meant everything.

While other families in the county married into neighboring towns, merged their fortunes with strangers, and diluted what they called their heritage, the Witors did something different. They looked inward. They married within the family, cousins to cousins, second cousins to third. They called it preservation. The town called it something else, but never loud enough for the Witors to hear.

By the time the 20th century arrived, the Witmore family tree didn’t branch outward. It coiled back on itself like a snake, eating its own tail. There were five main family lines, all interconnected, all living within a 10-mi radius of the original Witmore estate. They owned the land. They owned the mill.

They owned the church where they baptized their children and buried their dead. And they owned the silence of everyone who worked for them. But silence has a way of breaking. And in 1953, in a second floor bedroom of the Witmore Manor, something was born that no amount of money or land or pedigree could explain.

Something that should have remained buried, something with a voice that didn’t belong to it. The child was named Thomas Witmore V. His mother was Catherine Whitmore, 24 years old, daughter of a Witmore, and granddaughter of a Whitmore. His father was Richard Whitmore, 31, whose own parents were first cousins. This wasn’t unusual in the family. It was expected.

But what wasn’t expected, what no one had prepared for was the silence. For the first 6 weeks of Thomas’s life, he made no sound, not a cry, not a whimper, not even the small gurgles and coups that newborns make instinctively. The pediatrician examined him twice. There was nothing physically wrong with his throat, his lungs, his vocal cords.

He was simply silent, unnaturally, disturbingly silent. And then one night in late September, he screamed. Catherine was alone in the nursery. She had just set Thomas down in his crib when his mouth opened, and a sound came out that made her step backward and press her hand against the wall to steady herself. It wasn’t the high-pitched whale of an infant. It was deeper, raspier.

It sounded like someone who had spent years smoking cigarettes and screaming into the void. It sounded like someone old, and worst of all, it sounded familiar. Catherine Whitmore didn’t tell her husband about the scream. Not at first. She convinced herself she had imagined it, that exhaustion and the strain of new motherhood had twisted her perception.

But three nights later, it happened again. This time, Richard was in the room. He was standing by the window, looking out at the fields his family had owned for a century and a half. When Thomas opened his mouth and spoke, not cried, spoke, the word that came out was garbled, incomprehensible, but it had the shape of language. It had intention.

Richard turned slowly, his face drained of color, and looked at his six-week old son. Then he walked out of the room without saying a word. The family doctor was called again, then a specialist from Richmond, then another from Baltimore. They examined Thomas for hours, running tests that had no name in 1953, checking for abnormalities that medicine hadn’t yet learned to categorize. Every doctor came to the same conclusion. There was nothing wrong with the child.

His vocal cords were normal. His neurological development was normal. He was, by every measurable standard, a healthy infant. But healthy infants don’t sound like dying old men when they cry, and they certainly don’t form words. By the time Thomas was 3 months old, the sounds had become more frequent, more distinct.

Catherine started keeping a journal, writing down everything she heard, even though she knew how insane it would sound if anyone ever read it. On November 14th, she wrote, “He said, “Cold today. I know he said it. Richard heard it, too, but he won’t talk about it.” On November 22nd, he laughed. Not a baby’s laugh. It sounded like someone remembering a cruel joke. On December 3rd, he said a name.

I couldn’t make it out completely, but it sounded like Miriam. There’s no Miriam in our family. But Catherine was wrong. There had been a Miriam. Miriam Whitmore, born in 1897, died in 1926 at the age of 29. She had been Richard’s great aunt, his grandfather’s sister, and according to the few records that still existed, she had died under circumstances the family refused to discuss.

Her death certificate listed the cause as respiratory failure, but there was no funeral announcement in the local paper, no obituary, no grave marker in the family plot. She had simply vanished from the family narrative, erased as thoroughly as if she had never existed. Richard’s father, Jonathan Whitmore, was still alive in 1953. He was 71 years old, hard of hearing, and rarely left his room on the third floor of the manor.

But when Catherine mentioned Miriam’s name, something changed in his face, a tightness around his mouth, a flicker of recognition that he tried to hide but couldn’t quite manage. He told Catherine to stop asking questions. He told her that some names were better left unspoken, that the past should remain buried, that dredging up old family matters would only bring trouble. And then he asked her something that made her blood run cold.

Has the boy been saying other things, things he shouldn’t know? Catherine didn’t answer, but the truth was yes. Thomas had been saying other things, fragments of sentences that made no sense, references to places that no longer existed. On January 9th, 1954, while Catherine was changing his diaper, Thomas looked directly at her and said in that same rasping wrong voice, “The cellar door doesn’t lock anymore.” Catherine froze.

There was a cellar beneath the mana, but it had been sealed shut for decades, boarded up after some incident in the 1920s that no one in the family would explain. Richard had mentioned it once years ago when they were first married, but only to tell her never to ask about it.

That night, Catherine went down to the basement with a flashlight. She found the old cellar door behind a pile of furniture and moth eataten curtains, and she found something else. The boards that had sealed it shut were fresh. Someone had removed the old ones and replaced them recently. Within the last few months, she pressed her ear against the wood and listened.

From somewhere deep below, she heard water dripping and beneath that something else. A sound like breathing, slow, labored. Wrong. Catherine didn’t sleep that night. She lay in bed next to Richard, listening to him breathe, wondering how many secrets he was keeping, wondering if he knew what was behind that cellar door, wondering if his father knew, wondering if the entire family had always known and she was the only one stupid enough to have married into it without asking the right questions.

When morning came, she made a decision. She would find out who Miriam Whitmore was, and she would find out what happened to her. The county records office was a 30inut drive from the mana. Catherine told Richard she was taking Thomas to see her sister in Charlottesville, but instead she drove to the courthouse in Ashefield with her son sleeping in a basket on the passenger seat. The clerk at the records office was an older woman named Mrs.

Brennan who had worked there for 40 years. When Catherine asked to see Miriam Whitmore’s death certificate, Mrs. Brennan’s expression changed. Not quite suspicion, not quite fear, something in between. She asked Catherine why she wanted to see it. Catherine said she was writing a family history. Mrs.

Brennan didn’t look like she believed her, but she went into the back room and returned 10 minutes later with a file so thin it could barely be called a file at all. The death certificate was dated March 17th, 1926. Cause of death, respiratory failure, place of death, Whitmore family residence, attending physician, Dr. Howard Stevens. But there was something else in the file. a handwritten note on a piece of paper that had yellowed with age.

It wasn’t signed, but the handwriting was careful, deliberate, like someone who wanted to make sure their words would be understood decades later. The note said, “Dr. Stevens requested county investigation March 19th. Request denied by Sheriff Whitmore. No autopsy performed. Body interred on family property without county oversight. This office advised to close matter and file accordingly.” Catherine read the note three times.

Sheriff Whitmore. That would have been Richard’s grandfather, Thomas Whitmore III. The same man whose name had been given to her son. The same man who had somehow made sure that no one looked too closely at Miriam’s death. She asked Mrs. Brennan if there were any other records, any police reports, any newspaper articles. Mrs.

Brennan shook her head. Then she leaned forward and said something quietly. So quietly that Catherine almost didn’t hear it. My mother worked for the Whit Moors back then. She was there the night Miriam died. She never told me what she saw, but I know it changed her. She wouldn’t set foot on that property ever again, not even for twice the wages.

Catherine drove home in silence. Thomas woke up once during the drive and made a sound that wasn’t quite a cry. It was more like a sigh, like someone exhaling after holding their breath for a very long time. When they arrived back at the manor, Richard’s car was in the driveway. So was his father’s nurse’s car.

Catherine carried Thomas inside and found Richard standing in the foyer, his face pale and tight. He told her his father wanted to see her alone. Without the baby, Jonathan Whitmore’s room smelled like old paper and camper. The curtains were drawn, and the only light came from a small lamp on the bedside table.

He was sitting in a chair by the window, a blanket draped over his lap, his hands folded on top of a leatherbound book. When Catherine entered, he didn’t look at her. He kept his eyes fixed on the window, even though the curtains blocked any view of the outside. He told her to sit. She sat. And then he began to talk. He told her that the Witmore family had kept itself pure for a reason, not because of pride, though there was pride.

not because of tradition, though there was tradition, but because they had made a choice a long time ago, back in the early 1800s, and that choice had consequences. He didn’t explain what the choice was. He didn’t say who had made it or why.

He only said that purity was necessary, that dilution would have been catastrophic, that every generation had understood this and had done what was required to maintain it. And then he said something that made Catherines hands go numb. He said Miriam didn’t understand. She thought she could break the pattern. She thought love was stronger than blood. She was wrong. Catherine asked what happened to Miriam.

Jonathan was silent for a long time. Then he opened the leatherbound book on his lap. It wasn’t a book. It was a journal. The handwriting inside was elegant, feminine, rushed in some places and painfully careful in others. Miriam’s journal. Jonathan turned to a page near the end and told Catherine to read it.

His voice was flat, emotionless, like he was reciting a grocery list instead of revealing a family secret that had been buried for nearly 30 years. The entry was dated March 10th, 1926. One week before Miriam died, she wrote about a man she had met. His name was Daniel Graves. He wasn’t from Ashefield. He wasn’t from Virginia.

He was a traveling salesman who had stopped in town for 3 days. And somehow in those three days, Miriam had fallen in love with him. Or maybe she had just fallen in love with the idea of him. The idea of someone who didn’t share her blood, who didn’t carry the weight of the Witmore name, who could offer her a life that didn’t involve marrying a cousin and producing another generation of children who looked too much like their parents.

She wrote that she was going to leave with him, that she had already packed a bag, that she was going to meet him at the train station on March 15th and never come back, but she never made it to the train station. The next entry in the journal was dated March 14th. The handwriting was different, shaky, desperate.

She wrote that her father had found out, that he had locked her in her room, that he told her she was sick, that she was confused, that the family would take care of her. She wrote that she could hear them talking downstairs. Her father, her brothers, the family doctor. She wrote that she was afraid.

And then the entry ended mid-sentence as if someone had taken the journal away from her while she was still writing. Jonathan closed the journal. He told Catherine that Miriam had become hysterical, that she had refused to eat, refused to sleep, refused to accept that leaving was impossible. He said the family had tried to reason with her, but she wouldn’t listen.

So, they did what they thought was best. They kept her in her room. They gave her medicine to calm her down. Medicine that Dr. Stevens had prescribed. Medicine that was supposed to help her rest. But Miriam didn’t rest. On the night of March 16th, she started screaming, not crying. Screaming.

screaming that she couldn’t breathe, that her chest was on fire, that something was wrong. Doctor Stevens was called, but by the time he arrived, it was too late. Miriam was dead, and the family decided that no one outside the family needed to know the details. Catherine asked where Miriam was buried. Jonathan pointed toward the window, toward the fields beyond the manor. He said she was buried on the property, unmarked, unmorned, erased.

And then he said something that made Catherine’s stomach turn. He said, “She’s still here. She never really left. Blood doesn’t leave. It just waits.” Catherine stood up to leave, but Jonathan grabbed her wrist. His grip was surprisingly strong for a man his age. He told her that Thomas was special. That the voice he carried wasn’t a curse.

It was a reminder, a warning. He said the family had tried to bury the past, but the past had found a way back through Thomas, through blood. He said Catherine needed to accept it, that fighting it would only make things worse.

And then he let go of her wrist and turned back toward the window as if the conversation had never happened. That night, Catherine couldn’t find Thomas. She had put him down for a nap in the nursery, but when she went to check on him an hour later, the crib was empty. She searched the entire second floor, then the first floor. Then she heard Richard’s voice calling her name from the basement.

She found him standing at the cellar door. The boards had been removed. The door was open. And from somewhere deep inside the cellar, she could hear Thomas crying. But it wasn’t Thomas’s voice. It was Miriam’s screaming, begging, pleading to be let out. Richard descended the cellar stairs first.

Catherine followed, her hands shaking so badly she had to grip the railing to keep from falling. The stairs were old, wooden, slick with moisture and something else she didn’t want to think about. The air grew colder with each step, and the smell hit her halfway down. Mildew and rot, and something sweet and sickening underneath it all, like flowers left too long in a vase.

The crying had stopped. Now there was only silence. The kind of silence that feels alive, that presses against your eard drums and makes you understand that something is waiting. At the bottom of the stairs, Richard turned on a flashlight. The beam cut through the darkness and illuminated a space that shouldn’t have existed.

The cellar was massive, far larger than the footprint of the house above. Stone walls stretched into shadows that the flashlight couldn’t reach. And in the center of the room, there was a crib. Not Thomas’s crib, an old one made of dark wood that had warped and cracked with age. Thomas was inside it, lying on his back, staring up at the ceiling.

He wasn’t crying anymore. He was smiling. And when the flashlight beam touched his face, he turned his head toward Catherine and spoke in Miriam’s voice, clear as a bell. You found me. Catherine ran to the crib and picked up Thomas, holding him so tightly he started to squirm. But the voice didn’t stop.

It kept talking. Kept using her son’s mouth to form words that belong to a dead woman. It said, “They put me down here. They told me it was for my own good. They told me I was sick. But I wasn’t sick. I just wanted to leave.” Richard stood frozen, the flashlight beam wavering in his hand. Catherine demanded to know what was happening.

Why Thomas was speaking like this. What the family had done. Richard didn’t answer. He just kept staring at the crib, at the dark wood, at the scratches carved into the sides. Scratches that looked like they had been made by fingernails. Then Catherine saw it in the corner of the cellar, barely visible in the flashlights glow, a shape.

At first, she thought it was a pile of old clothes, but as her eyes adjusted, she realized it was a body, or what was left of one. The skeleton was small, curled into a fetal position, still wearing the remnants of a white dress that had yellowed and rotted. And around the neck, there was a locket. Catherine knew that locket. She had seen it in old family photographs.

It had belonged to Miriam. Richard finally spoke. His voice was hollow, defeated. He said his grandfather had told him the truth when he turned 18. The same truth that every Witmore heir learned when they came of age. Miriam hadn’t died in her bedroom. She had died down here in the cellar after the family realized she wouldn’t stop trying to escape. They had brought her down here to calm down.

They had locked the door and they had left her for 3 days. Dr. Stevens had protested, had threatened to go to the authorities, but Sheriff Whitmore had made it clear what would happen if he did. So, Dr. Stevens had signed the death certificate, taken his money, and never spoke of it again. And the family had sealed the seller, and pretended it never happened. But blood remembers. Blood carries memory.

And when generations of Whitmore married each other, when the same genetic material circled back on itself again and again, those memories didn’t fade. They concentrated. They grew stronger. Until finally, in Thomas, they found a voice again. If you’re still watching, you’re already braver than most.

Tell us in the comments what would you have done if this was your bloodline. Catherine carried Thomas up the stairs and out of the cellar. Richard stayed behind. She could hear him down there moving things, the sound of stone scraping against stone. She didn’t ask what he was doing. She didn’t want to know.

She took Thomas to the nursery and held him until the sun came up. And for the rest of that night, he didn’t make a sound. Not Miriam’s voice. not his own, just silence, the same unnatural silence he had been born with. In the morning, Richard told her they were leaving. He had already packed bags for all three of them.

He said they couldn’t stay in the house anymore, that it wasn’t safe, that something had been released that couldn’t be put back. But Catherine knew the truth. You can’t run from blood. You can’t pack it in a suitcase and leave it behind. Thomas would carry Miriam’s voice wherever they went. And eventually he would carry other voices too.

All the voices of all the Witmores who had suffered in silence, who had been erased, who had been sacrificed to keep the bloodline pure. They moved to Maryland, a small town called Eastern, where no one knew the Whitmore name, where Richard could find work at a local bank and Catherine could pretend they were a normal family. They rented a house on a quiet street lined with oak trees.

They introduced themselves to the neighbors. They went to church on Sundays. They did everything they could to build a life that had nothing to do with the manor, the cellar, or the voices. For 6 months, it almost worked. Thomas grew. He learned to sit up, to grab objects, to smile at his mother when she sang to him. And most importantly, he made normal baby sounds, coups and gurgles, and eventually something that almost sounded like mama.

Catherine let herself believe that distance had broken whatever connection existed between her son and the dead. But on Thomas’s first birthday, everything changed. Catherine had baked a small cake. Richard had bought a wooden toy train. They had invited two couples from the neighborhood who had children around Thomas’s age. It was supposed to be ordinary, safe. But when Catherine brought out the cake with a single candle burning on top, Thomas looked at the flame and spoke.

“Not in Miriam’s voice this time. In a man’s voice, deep, authoritative, cold,” he said. The choice was made in 1809. We agreed to the terms. The land would be ours. The prosperity would be ours. But the blood had to stay pure. That was the bargain.

The neighbors laughed nervously, thinking it was some kind of trick, some recording device hidden in the high chair. But Catherine and Richard knew better. They saw the way Thomas’s eyes had changed. Not the color, the awareness behind them, like someone else was looking out through his face. someone who had been waiting a very long time to speak.

Richard quickly ushered the neighbors out, making excuses about Thomas being tired, about needing to reschedu. And when the house was empty, he sat down across from Catherine and told her what his grandfather had told him. The story that every Whitmore heir eventually learned. The story that explained everything. In 1809, the Witmore family was failing. The land was barren.

The crops wouldn’t grow. debt was crushing them. Thomas Whitmore I the patriarch, the founder of the family line in Virginia, was desperate, and in his desperation, he sought help from someone the church would have called unholy. A woman who lived in the woods beyond the property line, a woman who knew things about blood and soil and the old agreements that predated Christianity. She told him she could make the land fertile again.

She could ensure prosperity for his family for generations. But there would be a price. The bloodline had to remain pure. No outside blood could mix with Whitmore blood. If it did, if the line was ever broken, everything would collapse. The land would remember, the dead would remember, and they would take back what was owed. Thomas Witmore, the first agreed.

He didn’t believe in curses or magic or old agreements. He believed in survival. And for 140 years, the family had honored that agreement. Even as the reasons for it faded from memory, even as it became just tradition, just the way things were done, but Miriam had tried to break it. She had fallen in love with an outsider.

And the family had stopped her the only way they knew how, by making sure she never left, by making sure her blood stayed where it belonged, in the ground, in the family, in the pattern. And now Thomas carried all of it. Not just Miriam’s voice, but the voices of everyone who had ever been bound to that agreement. Every Whitmore who had married a cousin out of obligation rather than love.

Every child born from unions that should never have happened. Every secret burial. Every sealed room. Every family member who had disappeared from the records without explanation. They were all inside him waiting for their chance to speak. Catherine asked Richard what they were supposed to do.

How they were supposed to raise a child who was haunted by his own ancestry. Richard didn’t have an answer. He only knew what his grandfather had told him. That leaving the land didn’t break the curse. It only delayed it. That sooner or later Thomas would have to return. Because the agreement wasn’t just with the family. It was with the land itself.

And the land was patient. Thomas stopped speaking in other voices after that night. But he didn’t go back to being a normal child either. He grew up quiet, watchful, like he was always listening to something no one else could hear. Catherine kept journals about his development, pages and pages of observations that she never showed to any doctor.

She wrote about the way he would stare at photographs of the Witmore estate and trace his fingers over the windows. She wrote about the nightmares he had, always the same one, a woman in a white dress standing at the end of a long hallway calling his name. She wrote about the time he was 7 years old and drew a picture in school of a house with a sellar underneath it.

And when the teacher asked him what was in the cellar, he said the ones who stayed. By the time Thomas turned 18, Catherine and Richard had convinced themselves that the worst was behind them. Thomas had graduated high school. He had been accepted to college in Pennsylvania. He had friends, or at least acquaintances.

He seemed normal enough, if a bit withdrawn. Richard’s father had died 3 years earlier, taking whatever remaining secrets he had to the grave. The manor in Ashefield had been sold to a developer who planned to tear it down and build condominiums. It seemed like the Witmore legacy was finally ending, like the family could finally be free.

But on the night before Thomas was supposed to leave for college, he told his parents he needed to go back back to Ashefield, back to the property, he said he could feel them calling. all of them, Miriam and the others, the ones whose names had been erased, whose deaths had been covered up, whose voices had been silenced for generations.

He said they needed to be acknowledged, they needed to be remembered, and he was the only one left who could hear them clearly enough to do it. Catherine begged him not to go. She told him it was just a house, just land, just dirt and stone and rotting wood.

But Thomas looked at her with eyes that were his and weren’t his at the same time, and he said, “It’s not the house, Mom. It’s the blood, and I can’t run from my own blood.” Thomas drove to Ashefield alone. Catherine and Richard followed 2 hours later, terrified of what they might find. When they arrived, the manor was still standing. The developer had apparently run into problems. structural issues, strange occurrences that made the workers refuse to return, equipment malfunctioning, people hearing voices coming from the walls. One worker claimed he had seen a woman in a white dress standing in a second floor window,

even though the entire building had been empty for months. The project had been abandoned, and Thomas was standing in the overgrown front yard, staring up at the house like he had never left. Catherine and Richard tried to convince him to leave, but Thomas wasn’t listening. He walked through the front door and they followed.

Inside, the house was worse than Catherine remembered. The furniture was gone, sold off or stolen. The wallpaper was peeling. There were holes in the floor where the wood had rotted through. But Thomas moved through the rooms like he knew exactly where he was going. He went to the basement. He went to the cellar door.

and he went down the stairs into the darkness with Catherine and Richard trailing behind him, their flashlights cutting weak beams through the black. The cellar looked different, smaller somehow. Or maybe it was just that Catherine’s memory had made it into something larger and more terrible than it actually was, but Miriam’s remains were still there in the corner, undisturbed, Thomas knelt beside the skeleton and placed his hand on the old yellowed fabric of the dress.

And then he began to speak, not in Miriam’s voice, not in the voice of Thomas Witmore I, in his own voice, but with a weight behind it that didn’t belong to an 18-year-old. He said the names, all of them, every Whitmore who had been erased from the family records. Every child born with defects and hidden away, every woman who had tried to leave and been stopped, every man who had questioned the pattern and been silenced.

He said their names out loud, one after another, until the list seemed endless, and as he spoke, something changed in the cellar. The air grew warmer. The oppressive weight that had hung over the space for decades began to lift. Catherine felt it. Richard felt it.

And when Thomas finally finished, when he had spoken the last name and fallen silent, the cellar felt empty in a way it hadn’t before. Not just empty of people, empty of presence, empty of the past. Miriam’s skeleton was still there, still wearing the locket, but it looked smaller now, fragile, just bones and fabric, and the remnants of a life that had been stolen, just a body waiting to be buried properly.

Thomas stood up. He told his parents that it was done, that the voices had stopped, that the agreement, whatever it had been, was broken now. Not because the family had failed to keep the bloodline pure, but because someone had finally acknowledged the cost, had finally said the names of the people who had been sacrificed to maintain it. He said the land didn’t want blood anymore.

It wanted truth, and now it had it. They buried Miriam in the town cemetery 3 days later. a proper burial with a headstone that bore her full name and the dates of her birth and death. Catherine contacted the few remaining Whitmore she could find, distant cousins who had moved away and changed their names and told them what had happened. Some of them came to the burial.

Most didn’t, but it didn’t matter. Miriam had a grave now, a place where people could remember her. A place where her story couldn’t be erased. Thomas never went to college in Pennsylvania. He stayed in Ashefield. He bought the manor from the developer for almost nothing and spent the next two years restoring it.

Not as a family home, but as something else, a historical site, a place where people could learn about the real history of families like the Wit Moors, the ones who hid their secrets behind wealth and respectability, the ones who sacrificed their own children to maintain an image of purity that was never real to begin with. and Thomas lived there alone in a house that no longer whispered.

Catherine visited him once a year after the burial. She asked him if he ever heard the voices anymore. He said no, but he said he could still feel them sometimes, like an echo in his chest, a reminder that blood has memory, that families carry their history whether they acknowledge it or not, and that the only way to break a curse is to stop pretending it was never there. The Witmore Manor still stands today.

If you drive through Ashefield, Virginia, you can see it from the road. There’s a small sign out front that says it’s open for tours on weekends. Most people drive past without stopping, but sometimes late at night, people report seeing lights in the windows, hearing voices, feeling like they’re being watched.

Thomas says it’s just the house settling, just old wood and old stone doing what old things do. But Catherine knows better. She knows that some places never really let go of the past. They just learn to live with it. And so do the people who carry that past in their blood. The photograph from 1953 still exists. It’s in a drawer in Catherine’s house, wrapped in tissue paper, tucked away where she doesn’t have to look at it, but she knows it’s there.

And she knows that someday someone will find it and ask questions. Questions about the woman who isn’t smiling. About the baby whose mouth is open. about the story that was buried for so long it almost became a ghost itself. And maybe that’s how it should be. Maybe the only way to honor the dead is to keep telling their stories. To keep saying their names.

To keep remembering that blood isn’t just biology. It’s memory. It’s history. It’s the voice of everyone who came before. Waiting for someone brave enough to

News

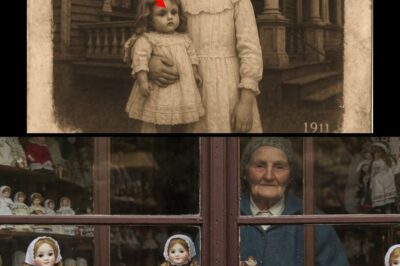

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze…

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze… In…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next Left Everyone Speechless…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next…

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn In the misty heart of the…

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras.

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras. In 1883, thirty…

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

End of content

No more pages to load