In the lexicon of American street culture, few phrases carry more weight than “checking in.” It’s a cardinal rule, a non-negotiable act of acknowledging territory and hierarchy when entering a rival’s domain. To ignore it is to invite violence. Yet, there was one man who moved through the most contested zones of 1980s Los Angeles with a universal pass. He wore what he wanted, went where he pleased, and was met not with hostility, but with a quiet, profound respect. That man was Michael Jackson.

The idea of the world’s biggest pop star navigating the deadly politics of the Crips and Bloods seems like a fever dream, a piece of urban folklore. But the story of how the King of Pop earned the untouchable respect of LA’s most notorious gangs is very real. It’s a narrative that unfolds not in back alleys, but on film sets and in boardrooms. It’s a testament to a man who understood power in its purest forms—cultural, financial, and personal—and wielded it not for intimidation, but for unity. This is the story of why Michael Jackson never had to check in.

To grasp the magnitude of his achievement, one must first understand the city he called home. By the early 1980s, Los Angeles was a city at war with itself. The rivalry between the Crips, formed in 1969, and the Bloods, who emerged shortly after as a counterforce, had metastasized into a brutal, city-wide conflict. Neighborhoods like Compton, Watts, and South Central became battlegrounds. Streets like Crenshaw and Slauson were cultural landmarks and front lines in a turf war defined by drive-by shootings and retaliatory killings. The Los Angeles Police Department’s aggressive CRASH unit often escalated tensions, creating a pressure cooker of fear and distrust.

Into this grim reality stepped Michael Jackson, who at just 24 was ascending to a level of superstardom the world had never seen. His 1982 album, Thriller, wasn’t just a hit; it was a cultural reset. As “Billie Jean” and “Beat It” conquered the charts in 1983, Jackson, now a Los Angeles resident, made a creative decision that would bridge two completely separate worlds. He decided the music video for “Beat It,” an anthem explicitly about rejecting violence, needed to be real. And to be real, it needed real people.

What followed was less a music video shoot and more a temporary peace summit on the gritty streets of Skid Row. The director, Bob Geraldi, and choreographer, Michael Peters, were tasked with bringing Jackson’s vision to life. The masterstroke was Jackson’s insistence on casting actual members of LA’s street gangs alongside professional dancers. It was a logistical and security nightmare. CBS Records refused to fund the risky $150,000 project, forcing Jackson to pay for it himself. In March 1983, a warehouse on East Fifth Street became a neutral zone, where dozens of young men with real-life rival affiliations were brought together for a shared purpose.

The tension on set was palpable. According to Geraldi, a moment of hostility nearly boiled over. But instead of calling security, Jackson made a move only he could. He reportedly asked for the music to be turned up and simply began to dance. The effect was immediate. The unsettled crowd grew still, watching him with a neutral, referee-like focus. In that instant, Jackson wasn’t a celebrity dabbling in street culture; he was a commanding presence whose art superseded any conflict. For a few hours, the lines blurred. Rivals stood side-by-side, not as enemies, but as collaborators in a cultural moment. The video’s climactic dance-off was more than choreography; it was infused with the lived experience of the men on screen. When “Beat It” premiered, it was a revelation—a powerful message of non-violence made authentic by the very people it sought to reach.

This single act laid the foundation for the respect he would command for the rest of his life. He hadn’t postured or pretended to be something he wasn’t. He had used his platform to offer inclusion and a message of peace, and the streets took notice. Hip-hop legend Eazy-E of N.W.A. later recalled encountering Jackson backstage and acknowledged that he was one of the few people who never had to check in. His presence alone was his pass. Both Crips and Bloods saw his intent, and it was pure.

But Jackson’s influence wasn’t confined to cultural gestures. He understood that true power operated on multiple fronts. His business acumen was just as sharp and strategic as his artistic vision. This was never more apparent than in his dealings with the music industry, which culminated in one of the most brilliant countermoves in entertainment history. In 2004, rapper Eminem released the music video for “Just Lose It,” which viciously mocked Jackson’s appearance and the infamous Pepsi commercial accident. While many expected a lawsuit, Jackson chose a different path.

In 2007, through his 50% ownership of the powerhouse Sony/ATV Music Publishing, the company acquired Famous Music LLC. The deal brought over 125,000 songs into the catalog, including some of Eminem’s biggest hits. Suddenly, Michael Jackson was part-owner of the music of the man who had publicly ridiculed him. He hadn’t retaliated with anger; he had responded with a corporate maneuver that turned an offense into a financial asset. This move was not lost on street communities, where strategic thinking and outmaneuvering an opponent without violence is a highly respected form of power. Jackson could win in the boardroom just as effectively as he could unite a film set.

The folklore that surrounds Jackson to this day—the playful jokes from comedians on the 85 South Show or the TikTok memes suggesting he was secretly a Crip because he wore blue—aren’t based in fact. There are no police records, FBI files, or credible accounts linking him to any gang. These jokes persist not because people believe them, but because they are a way to articulate the unexplainable paradox of Michael Jackson: he was a gentle, soft-spoken artist who carried an aura of untouchable power. The respect he commanded felt as real and unshakeable as that of any street legend.

He cemented this respect through quiet, consistent action. He invited youth from underserved neighborhoods to his concerts and his Neverland Ranch. He made unpublicized donations and visited communities scarred by violence. He didn’t do it for cameras or headlines; he did it because he believed in using his platform to uplift. He never claimed a set or a color, because his mission was unity.

Michael Jackson didn’t need to check in with the Crips or the Bloods because he had already checked in with humanity. His currency was not fear, but integrity. He entered the most contested territories armed not with weapons, but with a message of peace, a genuine spirit of generosity, and an artistic vision that was powerful enough to make even the bitterest of rivals pause and watch in awe. He never joined a gang; he invited everyone to join a shared purpose. That is the definition of true influence.

News

Michael Jackson Tomb Opened After 15 Years, His Kids Are SHOCKED…

Michael Jackson was more than a musician; he was a global phenomenon. As the King of Pop, his influence on…

At 58, Janet Jackson BREAKS Her Silence Leaving The World SHOCKED

The world stopped on June 25, 2009. News of Michael Jackson’s sudden death sent a seismic shockwave across the globe,…

Why Mariah Carey STILL VISITS Michael Jackson’s Grave To This Day

In the dazzling universe of pop music, few stars have ever shone brighter than Mariah Carey and Michael Jackson. To…

More Than a King: The Unforgettable Birthday Moments That Revealed the Real Michael Jackson

For most of the world, he was an icon, an otherworldly talent who moved with a grace that defied physics…

Why Michael Jackson was Misunderstood and Attacked More Than Anyone

The Untouchable Target: How Michael Jackson’s Greatness Became His Curse There are stars, there are superstars, and then there was…

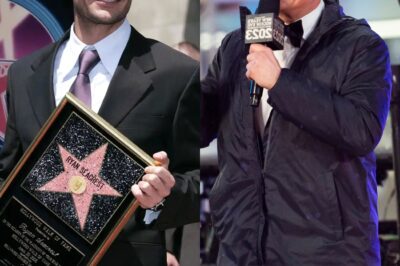

Ryan Seacrest surprised by the release of rare past photos: Fans laugh at his “dorky” past self!

Ryan Seacrest was caught off guard when rare past photos of him resurfaced, sparking amusement among fans. The beloved television personality,…

End of content

No more pages to load