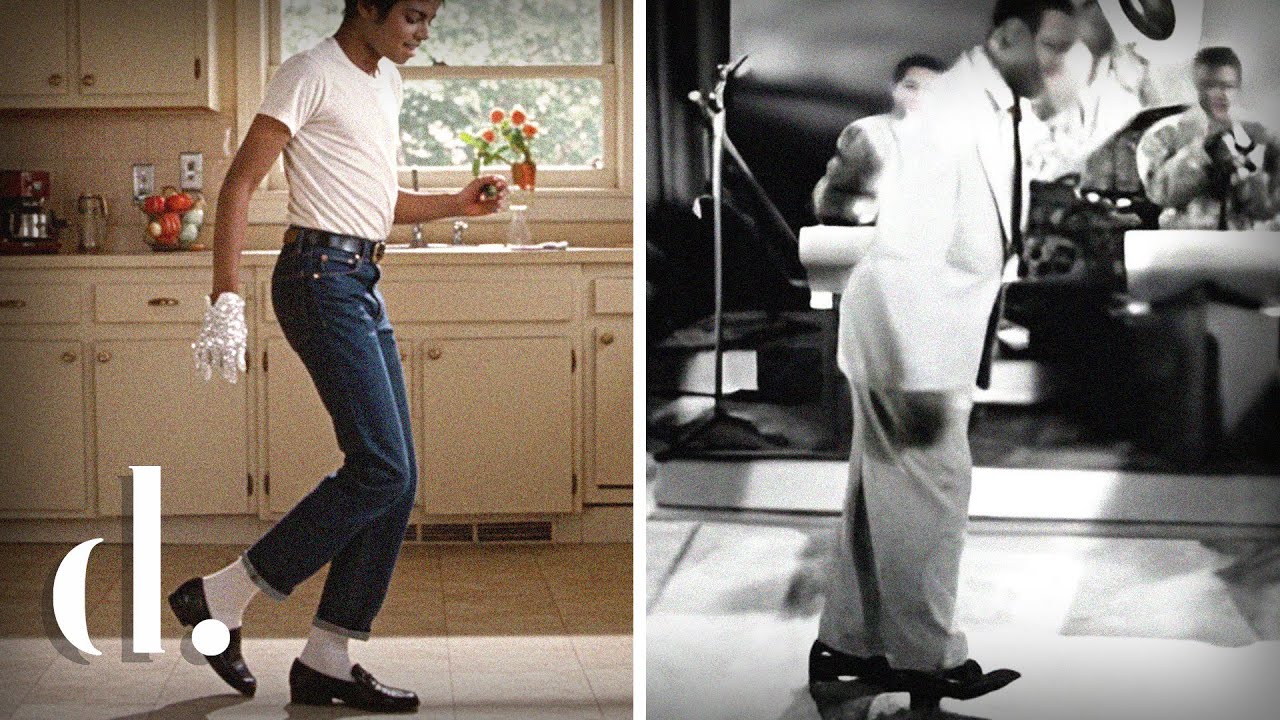

When most people think of the moonwalk, one image instantly comes to mind—Michael Jackson gliding backward on stage during his performance of Billie Jean on the 1983 Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever television special. That electrifying few seconds would etch the move into pop culture history forever. Yet, despite becoming his signature move, Jackson didn’t invent the moonwalk. Its roots stretch back decades, through the rich history of street dance and stage performance.

Trying to pinpoint the exact origin of the moonwalk is like trying to credit one person with inventing rock and roll—it’s impossible. The moonwalk is the product of decades of evolution in dance, particularly from Black performers. Cab Calloway, a legendary entertainer from the 1930s, claimed he had done similar moves during his performances. He jokingly said that in his day, they called it “The Buzz.”

The first known footage of a moonwalk-like move dates back to 1955, when dancer Bill Bailey performed a version on stage. Even then, the move wasn’t new—it had been passed along, evolving from generation to generation. But the person most often credited with directly influencing Jackson was Jeffrey Daniel, a member of the R&B group Shalamar and a dance icon on the show Soul Train.

Daniel, along with fellow dancers Casper and Cooley, helped perfect a move then known as the “backslide.” He was widely known in the R&B dance community for his mastery of popping and locking. Jackson, a fan of Daniel’s work, reportedly watched him on Soul Train and later sought him out for lessons. Daniel eventually contributed choreography to Jackson’s Bad and Smooth Criminal videos.

In a 1982 performance on the UK show Top of the Pops, Daniel showcased his moonwalk. The clip is now widely seen as one of the clearest visual links between the street-born dance and Jackson’s interpretation. Daniel never claimed to have invented the move, emphasizing that it emerged organically from the popping and locking culture of the 1970s and early ’80s.

In Michael Jackson’s 1988 autobiography Moonwalk, he admitted that the move wasn’t his invention. “The moonwalk was already on the streets by this time,” he wrote, “a popping type thing that black kids had created dancing on the street corners in the ghetto.” He credited “three kids” for teaching him the move—presumably Daniel, Casper, and Cooley. Jackson practiced it and combined it with his own signature flair for maximum impact during Motown 25.

Despite the explosive success of the performance, Jackson himself wasn’t completely satisfied. He later revealed he had planned to spin and stop frozen on his toes but couldn’t hold the pose as long as he wanted. Backstage, even as he received thunderous applause and compliments, Jackson was disappointed in the details only a perfectionist would notice.

His worries, however, were unfounded. The day after the show aired, Fred Astaire called Jackson personally and told him, “You really put them on their asses last night. You’re an angry dancer. I’m the same way.” Later, Astaire and his longtime choreographer Hermes Pan invited Jackson over and analyzed his Billie Jean performance step-by-step. For Jackson, it was the greatest compliment he could have ever received.

The truth about the moonwalk is more fascinating than the myth. It is a move shaped by decades of cultural innovation, passed from foot to foot through stages, clubs, and street corners before reaching the global stage. While Michael Jackson didn’t invent it, he elevated it—transforming a grassroots dance into an unforgettable icon of pop history.

News

Elvis Presley and Lisa Marie Presley Deliver a Tear-Jerking Duet of “Don’t Cry Daddy” That’s Nothing Short of Pure Magic! Their Voices Meld in Perfect Harmony, Creating an Emotionally Charged Performance That Will Leave You Breathless. Just When You Think It Can’t Get Any More Moving, Nostalgic Photos of Elvis and Lisa Flash Across the Screen, Adding a Sweet and Heartbreaking Touch. Get Ready for a Soul-Stirring Moment That Will Tug at Your Heartstrings and Stay Etched in Your Memory Forever!

Elvis Presley and Lisa Marie Presley Deliver a Tear-Jerking Duet of “Don’t Cry Daddy” That’s Nothing Short of Pure Magic!…

In 2004, André Rieu and His Johann Strauss Orchestra Enthralled the Audience in Trier, Germany, With Their Amazing Rendition of Ave Maria, Aided by Brazilian Vocalist Carmen Monarcha. Held in the Historic Backdrop of the Ancient Roman Amphitheater, This Performance Became a Highlight of Rieu’s Career, Fusing Monarcha’s Rich, Operatic Voice With the Sweeping Accompaniment of the Orchestra. The Choice of Ave Maria—a Timeless Piece Often Associated With Reverence and Solace—Added a Layer of Poignancy That Resonated Deeply With Those in Attendance

In 2004, André Rieu and His Johann Strauss Orchestra Enthralled the Audience in Trier, Germany, With Their Amazing Rendition of…

André Rieu’s Remarkable Act of Generosity: The Beloved Maestro Donates £360,000 to Provide Music Lessons for 1,000 Children, Cultivating Young Talent and Sharing the Transformative Power of Music to Inspire Generations Worldwide

André Rieu’s Remarkable Act of Generosity: The Beloved Maestro Donates £360,000 to Provide Music Lessons for 1,000 Children, Cultivating Young…

The duet between Sumi Jo and Dmitri Hvorostovsky in The Merry Widow is a mesmerizing display of vocal brilliance, bringing together two of the most iconic voices in opera. The chemistry between the soprano and baritone is palpable, making their collaboration truly unforgettable.

The duet between Sumi Jo and Dmitri Hvorostovsky in The Merry Widow is a mesmerizing display of vocal brilliance, bringing…

Watching Vladimir Horowitz play Chopin’s Polonaise in A flat major Op. 53 at the Vienna Musikverein, even at the age of 84, is nothing short of mesmerizing. His mastery over the piano, honed over decades of relentless practice and deep musical understanding, is evident in every note he strikes. The way his fingers delicately and precisely touch the keys, extracting the most nuanced tonal qualities from the strings, is an art form in itself. As a retired professional photographer who had the privilege of documenting the unveiling of Horowitz’s portrait at Steinway Hall, I can attest to the awe-inspiring presence he exuded.

Watching Vladimir Horowitz play Chopin’s Polonaise in A flat major Op. 53 at the Vienna Musikverein, even at the age…

On stage, two great voices blended together, creating an emotional performance. Celine Dion, with all respect and professionalism, followed Luciano Pavarotti’s every beat, making sure every note was perfect. She not only sang with him, but also listened, felt, and honored an opera legend. Pavarotti, with his strong and powerful voice, seemed to lead Celine into another world – where music is not just melody, but the purest emotion.

On stage, two great voices blended together, creating an emotional performance. Celine Dion, with all respect and professionalism, followed Luciano…

End of content

No more pages to load