“No one thought she could make children sit still for two hours listening to the organ.” — But then Anna Lapwood walked out, told a story, and turned a restless hall into rapt silence.

At first, the room was chaos. Teachers whispered instructions, students shuffled in their seats, the low hum of chatter and fidgeting filled the air. Everyone knew what usually happened during “educational concerts”: the novelty lasted five minutes, then boredom set in. The organ, after all, was a museum piece to most of them — too big, too old, too serious.

And then Anna Lapwood stepped onto the stage.

Dressed simply, smiling as if she had a secret, she looked nothing like the stern image of an organist they imagined. “Let me tell you the story of the organ,” she began. Her voice was calm, conspiratorial, as though she were inviting them into a mystery. The murmurs quieted. Curious eyes turned forward.

She did not begin with Bach or dusty theory. She began with a story: of candlelit cathedrals, of kings and queens, of ancient churches where sound seemed to breathe through stone. And then she placed her hands on the keys.

A single chord rumbled through the hall — deep, resonant, shaking the floor like a giant exhaling. The students froze. Before the awe could fade, she shifted stops and launched into something instantly familiar: Harry Potter’s “Hedwig’s Theme.” The high notes shimmered like silver light above their heads. Suddenly, the organ wasn’t an old instrument. It was Hogwarts itself. A murmur of delight spread, then silence again as they leaned in, transfixed.

From there, Anna wove her spell. She projected simple diagrams showing how the organ’s pipes worked, then pulled each stop in turn to demonstrate. A flute. A trumpet. A choir of voices. She laughed at herself, calling it “painting with sound.” The children giggled — and then began whispering the stop names under their breath, as though learning a secret language.

But the true magic came when she said softly: “Now let’s go to space.”

With that, she played Hans Zimmer’s Interstellar. The low pedals thundered like rockets igniting, while the melody soared above like a fragile star. During “Cornfield Chase,” the music floated, wide and shimmering. By the time she reached “No Time for Caution,” her feet were racing across the pedals, both hands attacking three manuals at once, and the organ roared like the cosmos opening. The children did not move. One boy pressed his hand to his chest, eyes wide, feeling the vibrations shake his ribs.

Two hours passed. No one left. No one drifted off. They laughed at her stories of sneaking into the organ loft at midnight, held their breath during her hushed chords, and followed every rise and fall like it was the soundtrack of their own imagination.

When the final piece ended, Anna did not bow immediately. She asked them all to put a hand over their hearts. “Can you feel the last note still ringing?” she whispered. For a moment, the room was utterly still. Then, like a dam bursting, hundreds of children leapt to their feet, clapping, cheering, some even shouting. The ovation was as loud as any stadium rock concert.

One teacher, stunned, turned to a colleague and said: “She turned an instrument into magic.”

Videos of Anna’s approach have since gone viral: her glowing organ arrangements of Interstellar at the Royal Albert Hall, her playful Harry Potter clips on TikTok, her YouTube lessons on how the pipe organ works. Millions who once thought of the instrument as boring or irrelevant have been captivated by the way she makes it breathe.

What she did that day was not simply to perform. She built a bridge. She showed children that music is not something to be endured, but something to be lived — to be felt in the chest, to be carried in the imagination.

In an age when attention spans are measured in seconds, Anna Lapwood proved that with story, honesty, and wonder, even a thousand-year-old instrument can hold the future in its hands.

And for those children, the memory of sitting still — not because they had to, but because they wanted to — will last far longer than the sound of any chord.

News

Black Teen Handcuffed on Plane — Crew Trembles When Her CEO Father Shows Up

Zoe Williams didn’t even make it three steps down the jet bridge before the lead flight attendant snapped loud enough…

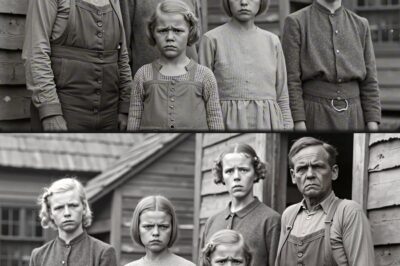

The Fowler Clan’s Children Were Found in 1976 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans

In the summer of 1976, three children were found living in a root cellar beneath what locals called the Fowler…

He Ordered a Black Woman Out of First Class—Then Realized She Signed His Paycheck

He told a black woman to get out of first class, then found out she was the one who signs…

Cop Poured Food On The Head Of A New Black Man, He Fainted When He Found Out He Was An FBI Agent

He dumped a plate of food on a man’s head and fainted when he found out who that man really…

Black Billionaire Girl’s Seat Stolen by White Passenger — Seconds Later, the Flight Is Grounded

The cabin was calm until Claudia Merritt, 32, tall, pale-kinned, sharp featured daughter of Apex Air’s CEO, stepped into the…

Four Men Jumped a Billionaire CEO — Until the Waiter Single Dad Used a Skill No One Saw Coming

The city’s most exclusive restaurant, late night, almost empty. A billionaire CEO just stood up from the VIP table when…

End of content

No more pages to load