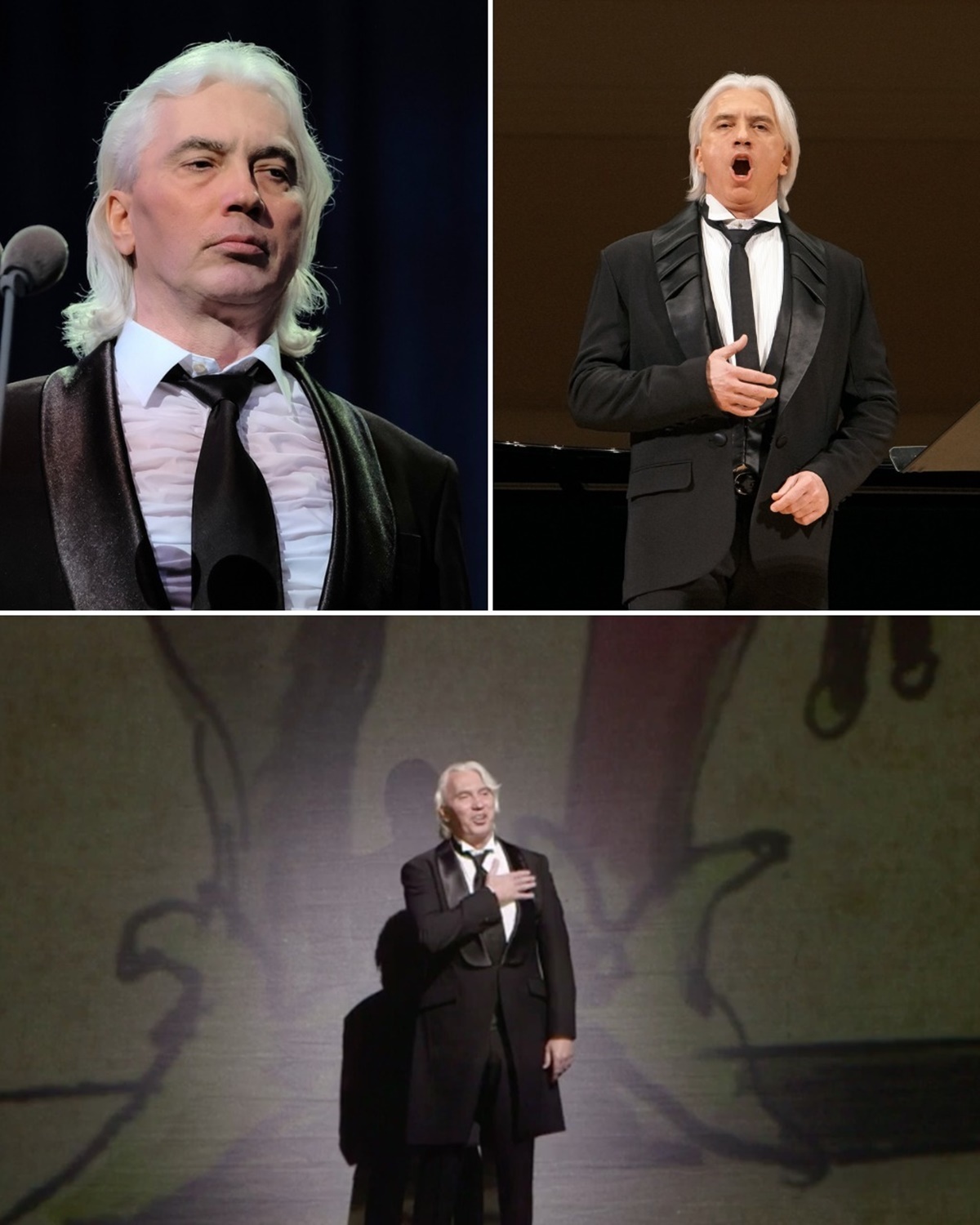

Hvorostovsky, the Siberian baritone known for his silvery hair and aristocratic stage presence, had stunned the opera world just months earlier by announcing he had been diagnosed with a brain tumor. Many assumed they might never see him on stage again. Yet here he was, defiant, elegant, luminous.

The curtain rose, and the audience erupted before he sang a note. A standing ovation thundered through the Met, wave after wave of applause that seemed as much a gesture of solidarity as admiration. Hvorostovsky bowed deeply, visibly moved, his trademark silver mane gleaming under the stage lights. Then, as the ovation finally faded, the orchestra began, and he sang.

“Il balen del suo sorriso” — Singing Through Mortality

The aria “Il balen del suo sorriso” is one of Verdi’s great declarations of passion: Count di Luna, obsessed with Leonora, pours out his longing in a melody both noble and haunted. In Hvorostovsky’s hands that night, it became something more.

His baritone rang with velvet richness, controlled yet brimming with urgency. Every phrase seemed carved from both strength and fragility. The audience knew the truth: this was not just a character yearning for love. This was a man confronting life, death, and the fleeting gift of song.

Critics later wrote of that performance as “a masterclass in courage.” One noted: “Hvorostovsky wasn’t merely performing Verdi. He was living him, every syllable colored by the knowledge of mortality.” Another declared: “It was singing that reminded us why opera exists: to hold the human soul to the light.”

The Ovation That Wouldn’t End

When the aria ended, the hall exploded again. People shouted, sobbed, clapped until their hands ached. The ovation lasted minutes, breaking the rhythm of the opera itself. The cast, the orchestra, even the conductor paused, understanding this was not a typical night at the opera. It was history.

Hvorostovsky stood tall, bowed slightly, and allowed himself a small smile. He did not grandstand, did not milk the moment. He simply acknowledged the love pouring toward him, then returned to his role with quiet dignity.

Beyond Music

For opera lovers, Hvorostovsky had long been a titan. From his 1989 victory at the Cardiff Singer of the World competition to decades of triumphs at Covent Garden, Vienna, and the Met, he had built a career on artistry, charisma, and that unmistakable “Siberian steel wrapped in velvet” voice.

But on that night in 2015, he transcended career. He became a symbol. A reminder that art is not about perfection, but about humanity — about carrying beauty into the world even as darkness closes in.

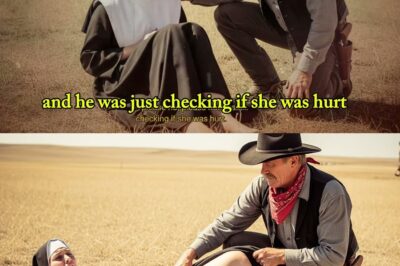

Legacy of the Black Shirt

The black shirt itself became a symbol. Stripped of costume armor, Hvorostovsky seemed both regal and vulnerable. Fans later called it “the shirt of courage,” an image burned into memory: the silver-haired baritone standing alone in black, commanding the Met not with power but with resilience.

Hvorostovsky continued to perform for two more years, often against medical odds, until his passing in November 2017. But for many, that May evening at the Met remains the defining image of his legacy.

Opera fans still return to the video of that aria, replaying the moment when applause and music blurred, when a performance became testimony, when an artist gave everything he had left and more.

It wasn’t just Verdi’s aria. It was Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s love letter to life.

Hvorostovsky, the Siberian baritone known for his silvery hair and aristocratic stage presence, had stunned the opera world just months earlier by announcing he had been diagnosed with a brain tumor. Many assumed they might never see him on stage again. Yet here he was, defiant, elegant, luminous.

The curtain rose, and the audience erupted before he sang a note. A standing ovation thundered through the Met, wave after wave of applause that seemed as much a gesture of solidarity as admiration. Hvorostovsky bowed deeply, visibly moved, his trademark silver mane gleaming under the stage lights. Then, as the ovation finally faded, the orchestra began, and he sang.

“Il balen del suo sorriso” — Singing Through Mortality

The aria “Il balen del suo sorriso” is one of Verdi’s great declarations of passion: Count di Luna, obsessed with Leonora, pours out his longing in a melody both noble and haunted. In Hvorostovsky’s hands that night, it became something more.

His baritone rang with velvet richness, controlled yet brimming with urgency. Every phrase seemed carved from both strength and fragility. The audience knew the truth: this was not just a character yearning for love. This was a man confronting life, death, and the fleeting gift of song.

Critics later wrote of that performance as “a masterclass in courage.” One noted: “Hvorostovsky wasn’t merely performing Verdi. He was living him, every syllable colored by the knowledge of mortality.” Another declared: “It was singing that reminded us why opera exists: to hold the human soul to the light.”

The Ovation That Wouldn’t End

When the aria ended, the hall exploded again. People shouted, sobbed, clapped until their hands ached. The ovation lasted minutes, breaking the rhythm of the opera itself. The cast, the orchestra, even the conductor paused, understanding this was not a typical night at the opera. It was history.

Hvorostovsky stood tall, bowed slightly, and allowed himself a small smile. He did not grandstand, did not milk the moment. He simply acknowledged the love pouring toward him, then returned to his role with quiet dignity.

Beyond Music

For opera lovers, Hvorostovsky had long been a titan. From his 1989 victory at the Cardiff Singer of the World competition to decades of triumphs at Covent Garden, Vienna, and the Met, he had built a career on artistry, charisma, and that unmistakable “Siberian steel wrapped in velvet” voice.

But on that night in 2015, he transcended career. He became a symbol. A reminder that art is not about perfection, but about humanity — about carrying beauty into the world even as darkness closes in.

Legacy of the White Shirt

The white shirt itself became a symbol. Stripped of costume armor, Hvorostovsky seemed both regal and vulnerable. Fans later called it “the shirt of courage,” an image burned into memory: the silver-haired baritone standing alone in white, commanding the Met not with power but with resilience.

Hvorostovsky continued to perform for two more years, often against medical odds, until his passing in November 2017. But for many, that May evening at the Met remains the defining image of his legacy.

Opera fans still return to the video of that aria, replaying the moment when applause and music blurred, when a performance became testimony, when an artist gave everything he had left and more.

It wasn’t just Verdi’s aria. It was Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s love letter to life.

News

Flight Attendant Calls Cops On Black Girl — Freezes When Her Airline CEO Dad Walks In

“Group one now boarding.” The words echo through the jet bridge as Amara Cole steps forward. Suitcase rolling quietly behind…

Flight Attendant Calls Cops On Black Girl — Freezes When Her Airline CEO Dad Walks In

“Group one now boarding.” The words echo through the jet bridge as Amara Cole steps forward. Suitcase rolling quietly behind…

“You Shave… God Will Kill You” – What The Rancher Did Next Shook The Whole Town.

She hit the ground so hard the dust jumped around her like smoke. And for a split second, anyone riding…

Black Teen Handcuffed on Plane — Crew Trembles When Her CEO Father Shows Up

Zoe Williams didn’t even make it three steps down the jet bridge before the lead flight attendant snapped loud enough…

The Fowler Clan’s Children Were Found in 1976 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans

In the summer of 1976, three children were found living in a root cellar beneath what locals called the Fowler…

He Ordered a Black Woman Out of First Class—Then Realized She Signed His Paycheck

He told a black woman to get out of first class, then found out she was the one who signs…

End of content

No more pages to load