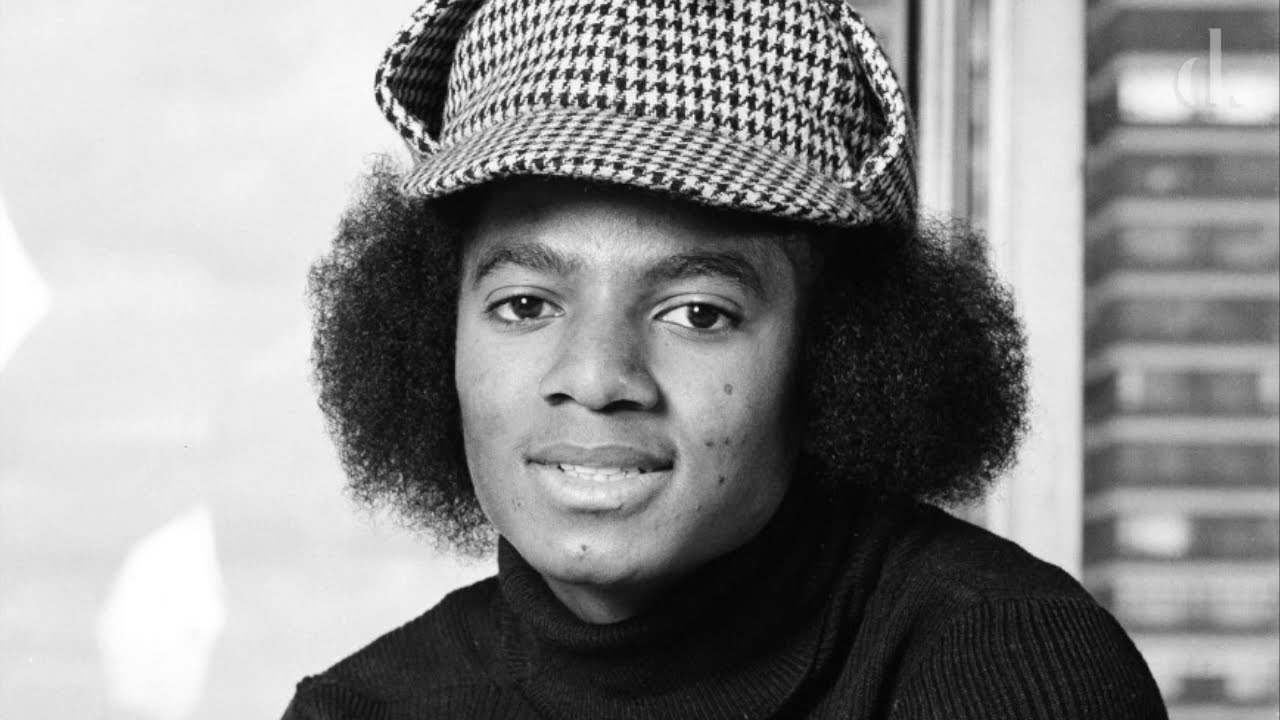

For decades, the private life of Michael Jackson has been the subject of relentless speculation, a fortress of myth and mystery guarded by whispers and tabloids. He was a global icon, a musical enigma, and, to many, a man who seemed to exist on a different plane of reality. But long before the world anointed him the “King of Pop,” he was just Michael—a shy, gentle young man navigating the rush of stardom. And he had a girlfriend.

Her name is Stephanie Mills.

In a stunningly candid and emotionally charged testimony, the Tony Award-winning singer and original star of “The Wiz” has broken a decades-long silence about her intimate relationship with Jackson. Her words paint a portrait so starkly different from the public caricature that it’s almost disorienting. She speaks not of an eccentric recluse, but of her first love, a “regular kind of guy” she once did laundry for.

“People don’t believe he ever had a black girlfriend,” Mills states, a note of lingering protectiveness in her voice. “I was his only little chocolate drop.”

Their romance, she explains, blossomed in the 70s and 80s, a more innocent time when “people didn’t kiss and tell.” It was a relationship shielded from the public eye, rooted in a shared experience of prodigious young talent. Mills, then the toast of Broadway, first met Michael when he would come to her show, “The Wiz,” and hang out backstage.

“Michael was really, really shy,” she recalls, “but I was aggressive.”

It’s a striking image: Mills, then just 15 or 16, and the already-famous Michael Jackson, finding a connection. “Every girl in America wanted to be Mrs. Michael Jackson,” she admits, “and I just knew that I was going to be Mrs. Michael Jackson.”

The relationship deepened significantly when Michael was cast as the Scarecrow in “The Wiz” movie. It was during this period that Mills was welcomed into his private, domestic world, a world no one else saw. “He lived on Sutton Place, and he was filming ‘The Wiz’ movie,” Mills reveals, sharing the intimate details for the first time. “I used to spend the night over there, and I would do his laundry. We would go down to the laundry together.”

This simple, domestic act—doing laundry—is the anchor of her story. It grounds the myth in a powerful, humanizing reality. Here was the biggest star in the world, and Stephanie Mills was washing his clothes and cooking for him.

“I even cooked for him, too,” she laughs. “Even though I couldn’t cook, as bad as it was, Michael was such a gentleman, he still ate it.” They were, for a brief, shining moment, just two young people in love. She emphasizes his normalcy, his “very real” nature, as a direct counter-narrative to the “soft” or strange persona that would later define him.

Mills is unflinching in her defense of his masculinity, a topic that has been cruelly debated for years. “People thought he was soft. He was not soft,” she declares firmly. “Michael is a great kisser. I kissed him. He’s a great kisser.”

She also clarifies the nature of their “overnight visits.” While she was deeply in love and “enjoying the ride,” the relationship remained innocent. “No, we never had sex. I never had sex with Michael,” she states plainly.

So, what shattered this idyllic romance? According to Mills, it was the inevitable collision of young love and unprecedented fame. She was ready for a future, but he was on the precipice of global domination.

“We broke up because I wanted to get married, and he wasn’t ready to get married,” she explains. “He wanted to experience other things.”

That desire to “experience other things” coincided with a profound shift in his life and, ultimately, his personality. The change, Mills pinpoints, happened “after ‘Billie Jean’ and that success.” The Michael she knew began to recede, replaced by a new figure surrounded by “the wrong type of people.”

She describes a clear schism in his social world. “He started hanging around yes, yes,” she confirms, alluding to a new, predominantly white inner circle. “I didn’t want to go to certain people’s houses for dinner… I wasn’t going to change myself.” This, she believes, was the beginning of the “crossover” pressure that she feels diluted his essence.

“In our entertainment world, they always tell you… I was ‘too black’ for this, ‘too black’ for that,” she says, “so they want you to cross over.” She watched as the man she loved, the “cool” and “regular” guy, began to change “into something else” as his pop success exploded.

The next time she saw him, on the set of his “Bad” video, the transformation was complete. “That was the first time I ever saw him when he had totally changed,” she says, a palpable sadness in her recollection. She approached him, whispering something in his ear, something to remind him of who he was, of their shared roots. “He knows I’m truly a black woman,” she says, “so I approached him in a whole ‘nother way.”

Despite the heartbreak of watching him change, Mills’s defense of his core character is perhaps the most powerful part of her story. She speaks of him with the fierce loyalty of someone who knew his soul.

“He was the most gentle, most kind… he never said a bad word about anybody. I’ve never seen him upset,” she insists. “The world wasn’t ready for Michael because he had so much love for everything and everybody that he was misunderstood. He was truly, truly misunderstood and very, very unhappy.”

Mills directly confronts the darkest shadow over his legacy: the pedophile accusations. Her denial is absolute and passionate. “He’s not a pedophile. Not at all.”

Her explanation for his affinity for children is both simple and devastatingly tragic. “Michael liked being around children because they were innocent,” she explains. “They didn’t want anything from him. They didn’t have an agenda.”

This, she contrasts sharply with the world of adults that surrounded him, a world of users and sycophants. “Most people around him had an agenda. They wanted something,” she says, recalling how she would “go to Havenhurst and see mothers drop their daughters off to stand at that gate and wait for Michael.”

In her view, his love for children was a desperate search for the one thing his fame had made impossible: genuine, unconditional affection. “They just like to play and have fun,” she says of children. “They’re not tainted, and they don’t judge you… That’s why he felt comfortable.”

Ultimately, Mills views Michael’s tragic life and tarnished legacy through the lens of race and a predatory industry. She rails against the double standard applied to black superstars.

“They always gotta end their lives with some mess,” she says, “but they don’t talk about Elvis Presley… they tolerate us in this business. They don’t celebrate us.”

She believes that in the end, after all the crossover success and all the efforts to appease a pop audience, Michael learned a bitter lesson. “No matter how much money you have, as a black entertainer, you’re still…” she trails off. “When his records began not to sell… he was no matter—and he’s the biggest selling artist in the world—but they looked at him like he was just another black artist.”

Her final words on him are not of tragedy, but of defiance. They are a reclamation of his crown, a final word from the woman who knew him first.

“Michael Jackson is the King, period. R&B, whatever. He’s the King, period. And that’s how I feel.”

Stephanie Mills’s story isn’t just a forgotten piece of celebrity gossip. It’s a vital, humanizing testament. It’s the story of a 15-year-old girl who did laundry for a shy boy she loved, and who watched as that boy became a king, and then a prisoner of his own kingdom. It’s a story of innocence lost, but of a love and loyalty that time could not change.

News

DYLAN DREYER BREAKS SILENCE: 𝘈𝘍𝘍𝘈𝘐𝘙 Exposed By Son, Mistress Identity Hinted, Fans Stunned By Emotional First Confession

DYLAN DREYER BREAKS SILENCE: 𝘈𝘍𝘍𝘈𝘐𝘙 Exposed By Son, Mistress Identity Hinted, Fans Stunned By Emotional First Confession Dylan Dreyer’s Shocking…

‘WAIT… WHAT?!’ Dylan Dreyer’s BOMBSHELL Announcement STUNS Craig and Savannah!

The first hour of *Today* looked a little different on Tuesday as viewers tuned in to find that beloved weatherman…

NBC SH0CKER: ‘Today’ Show Star Ousted Overnight — Tears, Scandals, and Backstage Mayhem Unfold as Fans Clamor for Answers! What Really Happened Behind the Scenes to Cause This Sudden Exit? Viewers Are Stunned as Secrets, Rivalries, and Hidden Conflicts Come to Light, Leaving the Beloved Morning Show in Complete Turmoil. Find Out the Explosive Details That No One Saw Coming in the Comments

nbc shocker: ‘today’ show star ousted overnight — tears, scandals, and backstage mayhem unfold as fans clamor for answers in…

Three months after announcing their separation, Dylan Dreyer was completely surprised when her husband, Brian Fichera, made a special gesture on the TODAY show. The simple yet heartfelt act brought both Dylan and the co-hosts to tears, with everyone calling it the most “heart-healing” moment of the year. While it’s unclear whether this unexpected gesture will bring them back together, it stands as a powerful reminder that love exists in many forms and never truly disappears.

Three months after announcing their separation, Dylan Dreyer was completely surprised when her husband, Brian Fichera, made a special gesture…

Dylan Dreyer revealed a moment that shattered that perfect image and reminded everyone that even TV’s most polished stars are still human. During what was supposed to be a simple family day out in New York City, Dylan experienced every parent’s worst nightmare — and it happened in an instant. Dylan’s story has struck a chord with parents everywhere — because behind the spotlight, she’s fighting the same chaos we all are. But the moment she revealed what truly happened that day in New York left everyone speechless

Dylan Dreyer revealed a moment that shattered that perfect image and reminded everyone that even TV’s most polished stars are…

“Dylan Dreyer is a sly fox!” – Tension erupts live on the Today Show. For 13 years, Dylan Dreyer had never strayed from the script — until this morning. In the final minute of the show, she suddenly cut off her co-host and revealed a secret she’d kept buried for four years, leaving the entire studio in stunned silence. No music. No applause. Just a chilling pause as Dylan looked straight into the camera and said something that froze everyone in place.

The Sly Fox Uncaged: Dylan Dreyer’s Four-Year Secret That Froze the Today Show For over a decade, Dylan Dreyer has been the picture…

End of content

No more pages to load