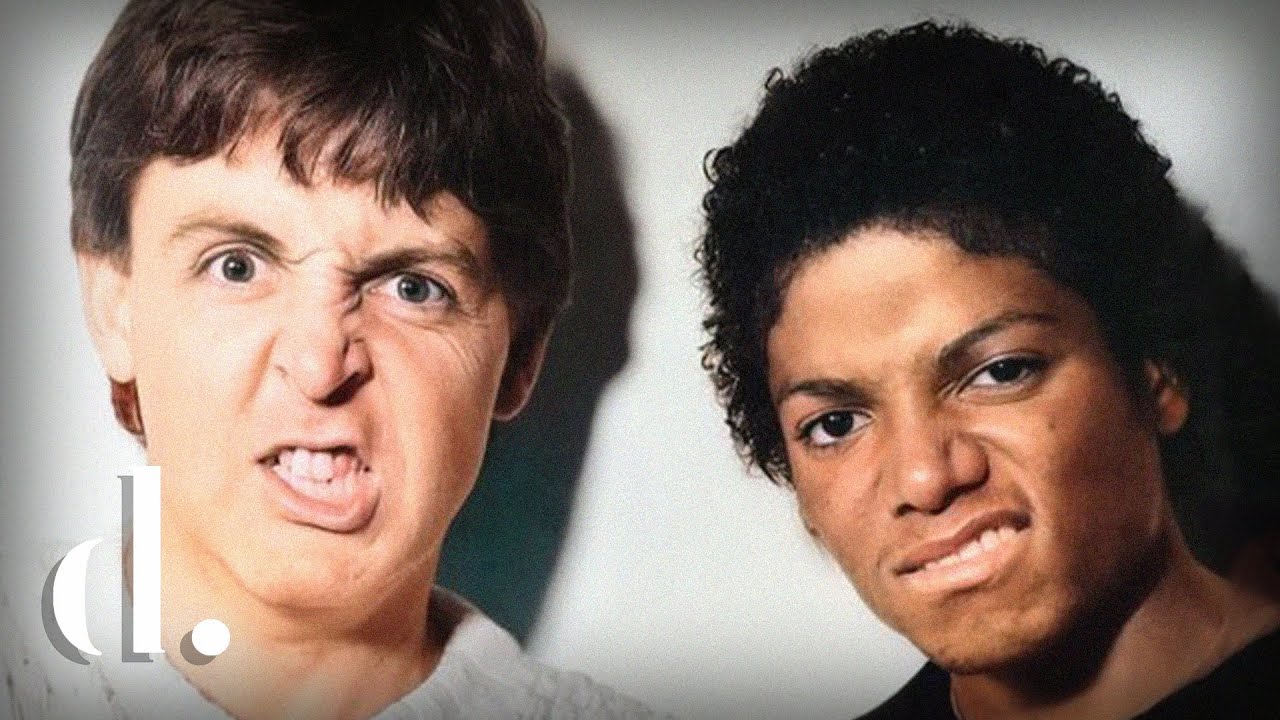

In the early 1980s, Michael Jackson and Paul McCartney were not just collaborators—they were friends. Their chemistry produced hits like “The Girl is Mine” (from Thriller) and “Say Say Say”, showcasing a playful rivalry over a woman. But just a few years later, that camaraderie would sour—over something far more serious than a fictional love triangle: music publishing rights.

The Early Bond: Music and Friendship

Their friendship began when Jackson recorded McCartney’s song “Girlfriend”, initially intended for Michael but released first by Paul’s band, Wings. Despite the mix-up, it ignited a musical partnership. In 1981, they collaborated further in London, with Michael even staying at Paul and Linda McCartney’s home. The pair grew close, often discussing songwriting and business.

One night, Paul showed Michael a notebook filled with songs he had acquired publishing rights to—classics like “Stormy Weather” and Buddy Holly’s catalog. He explained how music publishing was a goldmine, a lesson Paul learned the hard way after losing control of the Beatles’ publishing in the 1960s due to a public offering of Northern Songs.

Michael Learns the Business

Inspired, Michael told his attorney, John Branca, that he wanted to start buying music catalogs. By 1985, following the enormous success of Thriller, Jackson had the money to make big moves. When the ATV catalog, which held the rights to nearly every Beatles song, went up for sale, Branca asked Michael if he was interested.

Michael’s response? “I want it—please.”

Despite McCartney reportedly showing interest in reacquiring Beatles rights, he was not a serious bidder, possibly unwilling to pay for the non-Beatles material in the package. Jackson, however, made an aggressive offer and sealed the deal for $47.5 million—becoming the publisher of the Beatles’ catalog.

Fallout and Resentment

McCartney was blindsided. He had once taught Jackson the value of publishing—and now Jackson owned the rights to his songs. When the news broke, Paul received a call: “Michael bought your songs.” Paul called it “dodgy,” saying it was wrong to buy “the rug you’re standing on.”

Michael tried calling Paul to smooth things over, but Paul hung up every time. Eventually, Jackson stopped trying, telling people, “I’m finished trying to be a nice guy.”

The friendship collapsed, and tensions worsened when Jackson began licensing Beatles songs to companies. He sold “Revolution” to Nike, with Yoko Ono’s consent but not Paul’s. McCartney publicly criticized Jackson, arguing the music was being cheapened. For instance, “All You Need is Love” was used in a Panasonic ad, and McCartney feared other classics like “Good Day Sunshine” might be turned into cookie jingles.

Michael, on the other hand, believed he was helping Beatles music reach new generations. He reportedly told McCartney, “I’m enabling more people to hear and buy your music.” But Paul wasn’t having it. “I don’t think Michael needs the money. I don’t. And Yoko doesn’t either.”

A Failed Attempt to Reconcile

In 1990, Paul tried again to renegotiate the terms of his royalties with Michael. He explained how unfair it was that a fresh-faced 20-year-old contract could lock him in for life—even as Beatles hits like “Yesterday” reached record milestones. Michael seemed sympathetic at first, saying, “I don’t want to hurt anyone.”

But the next day, McCartney’s lawyer called Branca to work out a new deal. Branca called Michael, who denied making any promises. “He’s not getting a higher royalty unless I get something in return.”

The partnership that once thrilled fans had completely unraveled. Jackson’s ownership of the Beatles catalog—something he was taught to value by McCartney—became a wedge between them that was never repaired.

News

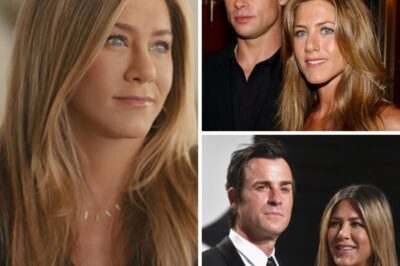

Jennifer Aniston has faced intense pressure from the media and the public over the years, revolving around a persistent obsession that has left her feeling deeply hurt. Behind the radiant star image lies a loneliness and misunderstanding that few people know about.

Jennifer Aniston has been hounded by pregnancy rumors for decades. As invested as fans are in Aniston’s life, it really isn’t…

The friendship between Jennifer Aniston and Matthew Perry contains many untold stories, especially the heartbreaking emotions when Aniston learned that Perry had silently endured suffocating pressure during the filming of Friends. Amidst the stage lights and audience laughter, few people expected that behind that closeness were moments of silence filled with hurt that Jennifer only fully understood after many years.

To the millions who watched Friends over its 10-year run and continue to revisit it decades later, the chemistry between the show’s…

After two failed marriages and a series of tumultuous relationships, Jennifer Aniston has revealed her strong belief that she will still meet the right person. Amidst the Hollywood glamour and a peaceful single life, the latest share from “Rachel” has made the public excited because of a possibility that is being quietly written.

After two failed marriages and a series of high-profile relationships that often made headlines more for heartbreak than happiness, Jennifer…

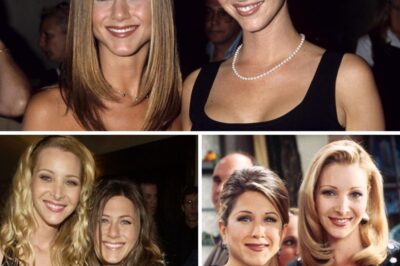

The friendship of more than 30 years between Jennifer Aniston and Courteney Cox has always been admired by the public, but few people know that there was a time when they almost lost each other. It was an unexpected event in their personal lives that made them realize the irreplaceable value of this friendship.

In the glittering world of Hollywood, where relationships often flicker and fade, the bond between Jennifer Aniston and Courteney Cox…

Jennifer Aniston and Lisa Kudrow’s decades-long friendship has always been admired, but few people know that there was a moment that almost caused the two to fall apart. It was that unexpected moment that became the glue that helped them become closer than ever.

Few friendships in Hollywood have endured as long—or as gracefully—as the bond between Jennifer Aniston and Lisa Kudrow. Known globally…

Jennifer Aniston and Courteney Cox not only shared a close friendship from Friends, but Jennifer also became a loving godmother to Lisa’s daughter. What has deepened their special bond with her over the years? A surprisingly heartwarming story awaits you!

Recently, the 54-year-old actress was spotted sharing a close and affectionate moment with her 18-year-old goddaughter, Coco Arquette. Coco is the only daughter of Courteney Cox and David Arquette, who were married in 1999 and later divorced in 2013. Courteney Cox, well-known for her role in Friends, is not only Coco’s mother but also a long-time close friend of actress Jennifer Aniston. The two actresses have maintained a strong friendship since their time working together on the iconic television series and are often seen supporting each other in both their personal and professional lives. Brad Pitt’s ex-wife burst into tears while leaning on her goddaughter Coco Arquette The two sat in the…

End of content

No more pages to load