The story at the heart of Gucci is extraordinary—passion, family feuding, love and loathing, tragedy, even murder. It’s better to cry in a Rolls-Royce than to be happy on a bicycle. That story is the real appeal, the excitement, the sex factor of a brand now worth fifteen billion dollars.

There’s an epic saying in Italy about family generations: the first creates, the second expands, and the third destroys. That’s almost exactly what happened in the Gucci story.

It began with founder Guccio Gucci, who had the vision for making quality leather goods and selling them to American tourists and European travelers. Then came his two sons, Rodolfo and Aldo, who each inherited fifty percent of the company. Aldo was the marketer and expander with a vision to take Gucci outside Italy—opening stores in Japan, Hong Kong, and across Asia with remarkable foresight.

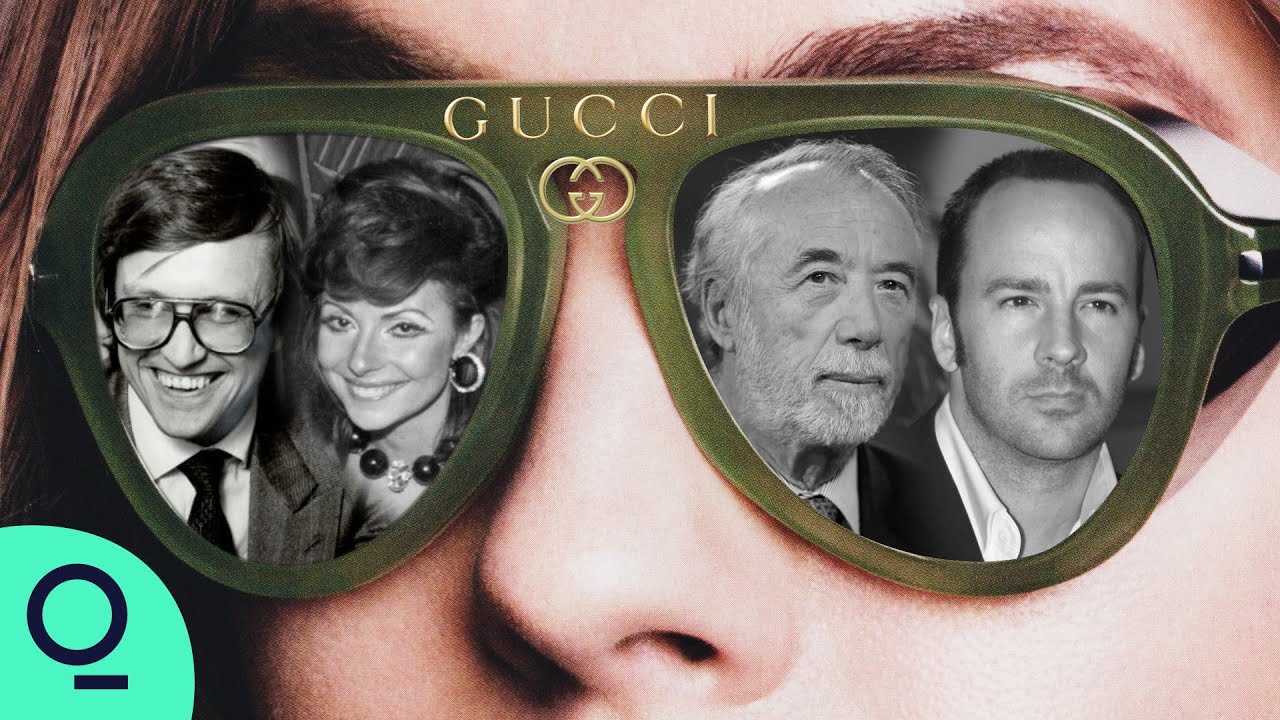

Then came the third generation, where conflicts erupted. Aldo had three sons—Roberto, Giorgio, and Paolo—who together with their father held fifty percent. On the other side stood Maurizio, Rodolfo’s only child, who would inherit the other fifty percent. The Gucci story became punctuated by family conflicts, extremely litigious battles that spilled into open court and became shockingly public.

The situation was complicated. Aldo’s children felt their father had done a phenomenal job—which was true—and deserved more than a quarter of fifty percent. Battles raged on and on. Aldo was formidable, but animosity festered. One son later said of another: “He dreams every five minutes. He doesn’t think, he dreams. And in his own life, he still runs like a child.”

The major turning point came in 1983 when Rodolfo died, leaving his fifty percent stake to his only son Maurizio. Maurizio already had ideas about cleaning up the Gucci brand and taking it upmarket, but he couldn’t get his uncle and cousins on board. They were happy with lucrative licensing deals that generated massive profits.

As Maurizio became more convinced of his vision—that he alone must take Gucci forward—his home life collapsed. His wife Patrizia had pushed him to become Mr. Gucci, one of Milan’s leading luxury CEOs. But he felt pressed, suffocated. In 1985, he left her. Mr. Jekyll became Dr. Hyde.

Meanwhile, Paolo turned on his own father. Suspecting Aldo of siphoning profits into offshore accounts, Paolo reported him to U.S. tax authorities. An IRS investigation began, eventually sending Aldo to prison.

Domenico De Sole, then the family’s lawyer, remembered explaining the gravity to the board: “This is the United States. Tax fraud is very serious. It’s not Italy.” One board member dismissed him as pessimistic. Unfortunately, Aldo did go to jail, and De Sole was asked to run Gucci America with the specific goal of settling with the IRS.

The reputation was still good—worldwide name recognition thanks to Aldo’s genius in opening stores everywhere early on. But the products were becoming less attractive. They’d expanded distribution dramatically. The brand was deteriorating, losing control of product quality in their drive for international success.

Maurizio had a problem: a clear vision for Gucci but no money to buy out his relatives. The answer came through investment banker Andrea Morante at Morgan Stanley. When Morante explained to his partners that Maurizio Gucci wanted shareholding restructuring, everyone was interested for the first time. That’s when Morante understood the power of a brand.

He launched a stealth campaign to buy shares from Aldo and the cousins, bringing in Investcorp as Maurizio’s financial partner. The complexity had one solution: inside information. Morante spent time with Maurizio, learning everyone’s agenda within the family.

Paolo had been ill-treated by his father after sending Aldo to jail, receiving significantly reduced shares compared to his brothers. Morante offered Paolo the same price his brothers would receive. Paolo accepted. Morante arrived with a suitcase of cash and purchased the initial three percent—a transaction that changed Gucci’s life forever.

One company worker called Paolo “a traitor to everyone.” Perhaps. But once the game was over and someone else was coming to run the business, they gradually sold their shares one by one. What seemed like mission impossible became reality. Investcorp purchased fifty percent, and together with Maurizio, they controlled the company.

Maurizio emerged as CEO with management control despite the fifty-fifty agreement. His vision was classic: round and brown and soft to a woman’s hand. He opened a fabulous Milan headquarters—no expense spared, priceless antiques, exquisite workmanship. The debt racked up fast. Simultaneously, he cut the most lucrative parts of the business, including the accessories collection that was the company’s cash cow.

Things were done irrationally. He incurred massive costs Italy couldn’t afford. He decided to clean out all old product. Overnight, he eliminated the GG logo. “That’s seventy percent of sales,” De Sole protested. But Maurizio wanted it at all costs. The company went into a tailspin, losing money catastrophically.

Gucci couldn’t pay salaries or suppliers. They teetered on bankruptcy’s brink. Some people have great vision, great strategy, but Maurizio was incapable of executing. That was the bottom line.

Investcorp, millions in the hole, stopped putting in money. De Sole told Maurizio it was in his best interest to choose a common new CEO, someone who could actually operate the business. The reaction was extremely negative—De Sole was essentially saying Maurizio couldn’t run the company. Maurizio begged for time, insisting that if they just gave him six months, the Japanese market would realize there was a new Gucci and sales would soar.

He never got that chance. Investcorp created a war room, went after him with everything they had, and successfully kicked him out. They bought his fifty percent for one hundred fifty million dollars and took over entirely.

The irony? Maurizio was right. Six months after being forced out, the Japanese woke up to the new Gucci and started buying bags. The company began making money hand over fist.

Then, in March 1995, one morning in broad daylight, Maurizio walked into his new offices. A gunman entered the doorway behind him and shot him dead in cold blood.

The murder shocked the city and was sinister because there was no clear culprit. The prosecutor investigated business deals and family conflicts, interviewed cousins and Patrizia, but saw no clear connection. The case went cold for two years until a tipster led police to raid Patrizia’s apartment at 5:30 one morning. She was arrested for Maurizio’s murder. She had an obsession—she wanted her husband dead and spoke about it to everyone.

Maurizio’s real legacy was that the Gucci brand had been created by three generations. After the third generation, the family couldn’t keep control. Maurizio not only lost control of the company but also his life.

Yet even though Maurizio wasn’t ultimately successful in implementing his vision, he’d done much of the work to set Gucci up for its next phase. He hired Dawn Mello from Bergdorf Goodman, and her main contribution was hiring Tom Ford.

After Maurizio left, De Sole quickly became Chief Operating Officer, essentially running the company. They asked him who should be Creative Director. He felt strongly it should be Tom. De Sole drove to Milan and met with the very young Tom Ford. “I think we can really fix this company,” he said. “I’m a businessman, not a creative person. You’re in charge. Let’s see where we go.”

Tom accepted. That was the beginning of the story.

Tom Ford brought back the logo and made it chic. He made clothes that rocked the world and put sex back where it belonged. His design power hit the fashion world like a tidal wave. It was clear from his very first menswear show in Florence that something had changed at Gucci. Sales took off immediately. Even though they showed sexy styles on the runway, they primarily sold black and brown handbags—but they’d lit a fire under the brand. Sales doubled.

In 1995, sales doubled again. The success was unbelievable. Investcorp wanted to go public as fast as possible. But they realized there was no fashion sector in the financial market, so they had to train analysts in how the luxury market worked. They really pioneered the luxury sector in financial markets, setting the stage for other brands to follow.

The Gucci IPO was even more successful than their wildest dreams. They debuted at twenty-two dollars and shot immediately to twenty-six. The offering was fourteen times oversubscribed, making more than two billion dollars for Investcorp. Sales were up one hundred thirteen percent—the fifth consecutive quarter they’d doubled sales.

But once it was clear the luxury market was there to be developed, the risk emerged that somebody could take it over. In 1997, when a financial crisis hit Asia, Gucci’s stock went down. LVMH started purchasing shares. Bernard Arnault, known as a corporate raider who’d taken over Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy, was making his move.

De Sole got a call saying LVMH had purchased five percent of Gucci—the threshold requiring public disclosure under New York Stock Exchange rules. That was the beginning of the battle with LVMH.

From January through June, two retail titans battled for control of fashion’s biggest prize. De Sole realized he was in for a big fight. He pulled in bankers and advisors to stage resistance. “They’re our number one competitor,” he said. “This is a case of creeping control. They want to control the company without paying the full price.”

The contest grew acrimonious. De Sole put protection mechanisms in place, issuing employee shares that diluted Arnault’s stake. But he realized they couldn’t fend off Arnault forever.

In the ninth hour, François Pinault, who ran PPR, a French retail group, came in offering to buy a stake in Gucci—the white knight to help fight off Arnault. Pinault was the most decisive man in history. De Sole talked to him for half an hour, explained why they wanted to defend against Arnault, and drove a hard bargain, securing three billion dollars for Gucci’s immediate growth—the very deal Bernard Arnault had rejected.

But Pinault had an even bigger idea. He turned Yves Saint Laurent over to Tom and Dom with three billion dollars, asking the dream team of fashion to buy other brands and turn Gucci into a multi-brand group rivaling LVMH.

It was brutal, done under immense pressure and great secrecy. Every time they tried to buy something, LVMH would show up. They acquired companies very fast—Alexander McQueen, Stella McCartney, Balenciaga. Some were young designers needing help to grow; others were faded names needing turnaround. They had many children to raise in this endeavor.

The agreement was that they’d run the company independently for five years, creating this large group, then Pinault would buy one hundred percent of shares at the price set during the LVMH battle.

Five years later, Pinault bought the full one hundred percent. Tom and Dom were running this publicly traded company as though it were their own. Until it came time to renegotiate contracts with Pinault taking control. They realized they wouldn’t have the freedom they’d had. Tom and Dom announced they were resigning from Gucci—a shock to the industry.

Tom was clear he wasn’t staying. De Sole, who’d worked so closely with him like a younger brother, felt they’d done their part. It was time to move on.

The partnership between Tom and Domenico became foundational not only for Gucci but for other luxury houses replicating the synergy between creative and management—the essential component for running a successful luxury brand.

“Gucci is my legacy,” De Sole said. “I love the company. I’m super happy about Gucci. I always wanted Gucci to do well. It would have been catastrophic if Gucci didn’t do well after Tom and I left.”

The genius of Gucci is how it’s been able to reinvent itself and reinvent the sex of its times. When Gucci was rescued in the 1990s, sex sold—that contemporary view on sex was fundamentally important. Now Gucci has gone ahead again with phenomenal success, expressing sex differently: gender-blending, non-binary sexuality that resonates with millennials and consumers under thirty-five. It’s been challenging for luxury brands, but Gucci made it a truly runaway and runway success.

From family warfare to murder, from near-bankruptcy to billion-dollar success, the House of Gucci stands as testament to the price of vision, the cost of control, and the eternal truth that in fashion, as in life, reinvention is the only path to survival.

News

From Icon to Inspiration: How Farrah Fawcett Transformed from America’s Golden Girl into a Courageous Cancer Advocate

A photograph once sold twelve million copies and claimed bedroom walls across America. The woman in that red swimsuit appeared…

Scarred by Fire: Allison Carey’s Dark Journey Through Prostitution, HIV, and the Sister She Burned—Mariah Carey’s Heartbreak

Born on August 7th, 1961, in Long Island, New York, Allison Carey entered a world that would test her from…

The Story of Janice Bryant Howroyd: The Billionaire Woman Everyone Ignored, Whose Humility Proved True Power Isn’t Always Seen

What impossible alchemy does it take to transform a meager $900 loan from one’s mother and $600 of personal savings…

The Lonely Billionaire Invited His Maid to Dinner, Unaware Her Kindness Would Expose His Empty Heart and Change His Life

It started with a silence that brought no peace, only a deep, echoing emptiness. Jonathan Blake sat alone at the…

Millionaire pretended to be a gardener and saw the black maid protecting his..

The people you trust the most are sometimes the very individuals you should have never allowed inside your home. This…

The Reckoning: 50 Cent, The Leaked Attorney Tapes, and The Juror Confessions That Shocked The Legal World

In the ever-evolving saga of Sean “Diddy” Combs, the intersection of celebrity feuds, serious criminal allegations, and high-stakes litigation has…

End of content

No more pages to load