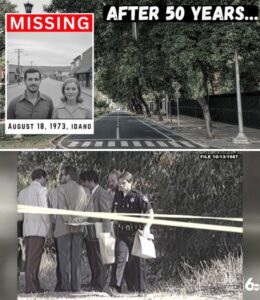

Dinner was still warm on the table when James and Rebecca Turner disappeared from their farmhouse on the edge of Cedar Ridge, Idaho. It was the evening of October 12th, 1973, a Friday when the wind carried the smell of pine and wood smoke through the valley, and pale lights from scattered homes flickered through the gathering darkness.

Their nearest neighbor, Agnes Crowley, glanced through her kitchen window around 11:30 and saw the Turner’s porch light still glowing, the faint hum of their radio drifting through the crisp autumn air. On the kitchen table, she could just make out two bowls of stew, steam no longer rising, and the coffee percolator still plugged into the wall.

By morning, every door was locked from the inside. The car sat untouched in the gravel driveway. When Agnes knocked at dawn, no one answered. What unfolded in the days that followed would become the most haunting mystery in Cedar Ridge for nearly 50 years.

Before we go further into this case, don’t forget to subscribe to the channel and hit the notification bell so you never miss the latest investigations. October 1973. Cedar Ridge, a quiet township of 3,800 people tucked along the Clearwater River in northern Idaho, still moved at the unhurried rhythm of a timber and farming community centered around the Clearwater Pulp Company and the small family plots that dotted the hillsides.

James Turner, 52, a millright at the pulp mill, was a man of steady hands and methodical temperament, known among co-workers for his precision and quiet dependability. His wife, Rebecca, 48, had worked as a nurse at the local clinic before leaving to care for their home and tend the rose garden that bloomed each summer behind their house.

They had two children, Linda, 24, recently married and living in Lewon, and Matthew, 19, a freshman at the University of Idaho in Moscow. The Turners lived in a modest two-story farmhouse on Old Pine Road about a mile from the river, surrounded by Douglas fur and open fields where fog settled thick on cold mornings. To neighbors and friends, they were the picture of small town respectability, hardworking, faithful, and unremarkably kind.

On Friday night, October 12th, the temperature dropped faster than usual, and a stillness settled over the valley as wood smoke curled from chimneys and porch lights blinked on one by one. Sometime after 8:00, Agnes Crowley heard the muffled sound of voices coming from the Turner House. Nothing alarming, just the low murmur of conversation, maybe a little sharper than usual, and then suddenly silence.

The living room light stayed on late into the night, casting a soft yellow glow through the curtains, but no one saw James or Rebecca step outside. The next morning, around 9:30, their daughter, Linda, arrived from Lewon for a planned weekend visit. She knocked on the front door. No answer.

She tried the back, locked. The car was still parked in the drive, keys hanging on the hook inside the mudroom window. Linda peered through the glass and saw her mother’s sweater draped over the chair by the radio. Two coffee cups on the counter, one still half full. She circled the house, calling out, her voice growing louder with each unanswered shout.

Finally, she drove to Agnes Crowley’s house and asked if she’d seen her parents leave. Agnes shook her head, troubled. Together, they returned to the farmhouse, checked every window, every door. Everything was locked from within. No sign of struggle, no note, just the steady ticking of the clock above the kitchen table.

By 11:00, Linda’s hands were shaking as she dialed the Cedar Ridge Sheriff’s Department from Agnes’ phone. The operator connected her to Sheriff Donald Hughes, who was finishing his morning rounds. Hearing the fear in her voice, he told her not to touch anything and said he’d be there within the hour. He grabbed his coat, motioned to two deputies, and drove out toward Old Pine Road and department’s mud spattered patrol car.

The dirt road leading to the Turner property was still damp from overnight dew, flanked on both sides by thick stands of pine. Morning light filtered weakly through the trees, and a thin mist clung to the fields. As Sheriff Hughes stepped out of the car and looked up at the silent farmhouse, the only sound was the wind moving through the branches and the distant call of a crow circling overhead.

“Or they finished and just didn’t clean up,” Mercer offered. “Hugh didn’t respond. He was looking at the back door now, a simple wooden frame with a single pane of glass at eye level. He tried the knob. Locked. The deadbolt was engaged.” He peered through the glass at the back porch.

a small wooden deck with a railing, a few potted plants, a metal wash tub leaning against the house. Beyond that, the yard sloped gently toward a line of pine trees, their dark shapes swaying in the breeze. Back doors locked, too, Hugh said. From the inside. He turned and walked back through the kitchen, pausing at the narrow hallway that led to the bedrooms and the seller stairs. The hallway was dim. The single overhead bulb turned off.

Hughes flicked the switch. Light flooded the cramped space, illuminating faded floral wallpaper in a small linen closet. At the end of the hall, the cellar door stood closed. Hughes moved toward the bedrooms first. The master bedroom was at the far end of the hall, its door halfopen. He stepped inside.

The bed was made, not hastily, but carefully, with the quilt smoothed and the pillows arranged just so. On the nightstand, a windup alarm clock ticked steadily, showing the correct time. A water glass sat beside it, empty. The closet door was a jar, revealing a neat row of hanging clothes. James’ work shirts, Rebecca’s dresses.

A pair of slippers sat on the floor beside the bed. The second bedroom, smaller and clearly used for storage or guests, was similarly undisturbed. Boxes stacked in one corner, a single bed with a thin blanket, a dresser with a layer of dust on top. Hughes returned to the hallway and stopped in front of the cellar door. He opened it slowly.

The hinges creaked. A draft of cool, damp air rose from below, carrying with it the smell of earth and concrete. A string hung from a bare bulb at the top of the stairs. Hughes pulled it. Yellow light spilled down the wooden steps. “I’m going down,” he said. Dalton followed. The stairs were steep and narrow, each step groaning under their weight.

At the bottom, the cellar opened into a low ceiling space with a packed dirt floor along the edges and a large section of poured concrete in the center. The walls were field stone and mortar, old and crumbling in places. Wooden shelves lined one wall stacked with dusty mason jars, paint cans, and a few rusted tools.

A workbench sat in the far corner, cluttered with hand saws, a coil of rope, and an oil lantern. Hughes scanned the room. The air was cool and thick, the kind of damp that settled into your lungs. In the center of the floor, he noticed a section of concrete that looked newer than the rest, lighter in color, the surface smoother, less stained. He crouched down and ran his hand over it.

“Looks like fresh cement,” Dalton said. “Could be,” Hughes replied. James was handy. “Maybe he was fixing something.” “Plumbing? Maybe.” Hugh stood and brushed the dust from his hands. He looked around the cellar again, his eyes lingering on the fresh patch of concrete, but there was nothing else that stood out.

No signs of disturbance, no blood, no broken furniture, just an old seller doing what old sellers did, holding up the house and gathering dust. They climbed back upstairs. Outside, Linda and Agnes were still waiting near the porch. Hughes stepped out into the daylight, squinting against the brightness after the dim interior of the house. He pulled a small notebook from his coat pocket and flipped it open. “Miss Turner,” he said.

“When did you last speak to your parents?” “Last Sunday,” Linda said, her voice barely above a whisper. “I called them after church. Everything was fine. Mama said they were planning a quiet week. Daddy had some work to finish at the mill.” “And your brother?” Matthew’s at school in Moscow. He was home the weekend before last. I think he called them earlier this week, but I’m not sure.

Hughes made a note. Did your parents have any plans to travel, visit anyone? Linda shook her head. No, they never went anywhere without telling me. Sheriff Hughes pushed open the gate and walked slowly up the gravel path toward the front door, his boots crunching softly in the morning cold. behind him. The two deputies exchanged uneasy glances.

The house looked ordinary, too ordinary, and that Hughes would later write in his case log was the first thing that felt wrong. Linda Turner stood on the porch with Agnes Crowley, her arms wrapped tight around herself, despite the wool cardigan she wore. Her eyes were red- rimmed, darting between the sheriff and the locked front door as if willing it to open, as if her parents might suddenly appear with some reasonable explanation.

a misunderstanding, a trip to town she’d somehow forgotten they’d mentioned. But Hughes had been doing this work long enough to recognize the look of someone who already knew deep down that nothing reasonable was coming. “Miss Turner,” Hughes said, his voice low and even. I need you to unlock the door for us, but once it’s open, I want you to step back and let us go in first. Don’t touch anything. Don’t move anything.

Understood? Linda nodded, her hand trembling as she fished the spare key from her purse. The lock turned with a soft click, and Hughes pushed the door inward. The air that greeted them was still and faintly stale, tinged with the smell of old coffee and something else. Woodm smoke maybe, or the lingering scent of Friday night’s dinner.

Hughes stepped into the entryway, his eyes sweeping left to right, cataloging everything. To his left, two coats hung on wooden pegs. A men’s heavy canvas jacket and a woman’s wool overcoat, both undisturbed. A pair of work boots sat neatly beneath them, laces tied.

To his right, the living room opened up, dim despite the morning light filtering through the thin curtains. Deputy Frank Dalton, a wiry man in his late 30s, moved past Hughes and into the living room. Deputy Tom Mercer, younger and quieter, stayed near the door. Notebook already in hand.

Front door was locked from the inside, Hughes said aloud, more for the record than anything else. Deadbolt engaged, no signs of forced entry. He moved deeper into the house. The living room was small but tidy. A floral patterned sofa sat against one wall, a knitted afghan folded across the back. An armchair faced the window, and draped over its arm was a woman’s cardigan sweater, pale blue, the kind Rebecca Turner might have worn on a cool evening.

On the side table next to the chair sat a pair of reading glasses, a folded church bulletin dated October 7th, and a small transistor radio, its dial still glowing faintly. Hughes leaned closer. The radio was on, tuned to a local station. The volume turned low enough that it was barely audible. A soft hiss of static and the distant murmur of a Sunday morning gospel program.

“Radio’s still on?” Dalton noted, glancing back at Hughes. “Hugh nodded.” He crossed to the far side of the room and tested the window latch. “Locked.” He moved to the next window. Also locked. Through the doorway, the kitchen came into view. Hughes walked slowly toward it, his boots heavy on the hardwood floor.

The kitchen was the heart of the house, and it told its own quiet story. Two bowls sat on the small dining table, each containing the remnants of what looked like beef stew, carrots, potatoes, chunks of meat gone cold and congealed in brown gravy. Beside the bowls were two spoons, a basket with three dinner rolls still inside, and a butter dish with the knife resting across it.

A coffee percolator sat on the counter near the stove, unplugged, but still half full. Next to it, two ceramic mugs, one empty, one with about an inch of coffee left, a faint ring of dried liquid along the rim. Hughes opened the refrigerator. Milk, eggs, a covered casserole dish, a few jars of preserves. Nothing unusual. He checked the stove. Cold.

The burner knobs were all in the off position, but there was a faint acrid smell lingering near the back burner. Something burned maybe hours ago. Looks like they stopped mid meal, Dalton said from the doorway. Agnes Crowley stepped forward, ringing her hands. Sheriff, I saw them Friday evening around 7:30, maybe 8.

I was doing dishes and I looked out the window. I can see their kitchen from mine and Ellen was clearing the table. Richard was sitting by the radio. Everything looked normal. Did you hear anything unusual later that night? Agnes hesitated. I thought I heard voices around 10 maybe a little louder than usual, but I didn’t think much of it.

Sometimes they’d have the radio up or they’d be talking then it went quiet. How long did the quiet last? I don’t know. I went to bed around 11:00. Their porch light was still on. Hughes turned to Dalton. Let’s talk to the neighbors. Anyone who might have seen something. Over the next two hours, they canvased the immediate area.

Most of the neighbors lived a quarter mile or more away, separated by fields and tree lines, but a few had relevant information. A man named Carl Jensen, who lived down the road, said he’d driven past the Turner house around 9:00 Friday night and noticed the lights on, but didn’t see anyone outside. A woman named Ruth Callahan recalled hearing a car engine idling somewhere nearby late that night, though she couldn’t say where it was coming from.

The most specific testimony came from a delivery driver named Roy Pitman who worked for the local grocery in town. Hughes tracked him down at the store just afternoon. “Yeah, I delivered to the Turners on Friday,” Pitman said, leaning against the loading dock. Around 4:00 in the afternoon, Mrs

. Turner answered the door. She was pleasant. Same as always. Paid in cash. Mr. Turner was out back. I think I heard him hammering something. Did they say anything unusual? Mention any plans? Nah. Mr. Turner joked about needing to fix a pipe in the cellar before winter. Said it had been leaking and he didn’t want it to freeze and burst. That was it. Hughes wrote it down. The cellar? Yeah, I remember because he said he’d already picked up some cement mix to patch the floor where the water had been pooling. Hughes closed his notebook slowly, his jaw tight.

He thanked Pitman and walked back to his car where Dalton was waiting. “Anything?” Dalton asked. James Turner was working on the cellar, Hugh said quietly, fixing a pipe poured fresh cement. Dalton frowned. “So that’s what we saw down there? Probably.” Hugh stared out at the road, his mind turning over the pieces. Everything pointed to a simple explanation.

A weekend trip, a sudden emergency, something mundane that would reveal itself in time. But the locked doors bothered him, the untouched car, the half-finished meal. That night, back at the station, Hughes sat at his desk and opened his case log. He clicked his pen and wrote in careful, deliberate handwriting.

October 14th, 1973 46, Old Pine Road, Turner Residence. Residence secured. No visible struggle. No signs of forced entry. Doors locked from interior. Vehicle present. Personal effects undisturbed. No indication of voluntary departure. He paused, the pen hovering over the page. Then he added one final line. No signs of departure. Cause of absence unknown.

He closed the log and leaned back in his chair, staring at the ceiling. Somewhere in the back of his mind, the image of that fresh concrete patch in the cellar lingered, a detail so ordinary it hardly seemed worth noting, but it stayed with him, quiet and insistent, like a word on the tip of his tongue. It would be 45 years before anyone thought to look beneath it.

By Monday morning, news of the Turner’s disappearance had spread through Cedar Ridge like frost across a windshield. quiet, inevitable, and impossible to ignore. At the diner on Main Street, voices dropped to murmurss over coffee and scrambled eggs. At the pulp mill, James Turner’s empty workstation became a focal point of hushed speculation during shift changes.

By Tuesday, the story had reached the churches, the school, the post office, every corner of the small town where everyone knew everyone, and secrets rarely stayed buried for long. At first, the reaction was one of collective concern. The Turners were well-liked, dependable, the kind of couple you could set your watch by. People wanted to help.

On Tuesday afternoon, Sheriff Hughes organized the first search party. 23 volunteers gathered at the fire station. Armed with flashlights, walking sticks, and thermoses of coffee, they fanned out across the fields and tree lines surrounding Old Pine Road, calling out the Turner’s names into the cold October air. Dogs were brought in from Lewon.

German Shepherds trained for search and rescue, their handlers guiding them along the muddy banks of the Clearwater River, where the current moved swift and dark beneath overhanging willows. For 3 days, the searches continued.

Volunteers combed nearly 10 square miles of terrain, dense pine forest, rocky ravines, abandoned logging roads that hadn’t seen traffic in years. They found deer trails and empty beer cans. A rusted out pickup truck from the 1950s slowly being reclaimed by blackberry vines. On the third day, a teenage boy named Danny Kowalsski discovered a torn piece of fabric snagged on a barbed wire fence about half a mile from the Turner property.

It was pale blue cotton, the kind that might have come from a woman’s blouse or a dish towel. Sheriff Hughes bagged it carefully and sent it to the state lab in Boise, though he had little hope it would lead anywhere. It didn’t. The fabric was too degraded, too generic. It could have been there for weeks. It could have belonged to anyone. By the end of the first week, the searches grew smaller. 15 volunteers became 10, then six.

The dogs were returned to Lewon. The town’s initial wave of compassion began to curdle into something else, something harder to name. At the diner, the murmurss shifted. Theories emerged, whispered across tables, and passed along in phone calls that stretched late into the evening. Maybe they were in debt. Maybe the mill was laying people off, and James couldn’t face it. I heard Rebecca had family out east.

Maybe they just left. Agnes said she heard arguing that night. What if it wasn’t an accident? What if something happened between them? The rumors grew legs. Someone claimed they’d seen James at a bar in Lewon a month earlier, drinking alone, looking troubled. Someone else swore Rebecca had mentioned wanting to leave Idaho, move somewhere warmer, start fresh. None of it was substantiated.

None of it mattered. In the absence of answers, people filled the silence with stories. And the stories, however flimsy, became a kind of truth. On October 21st, a candlelight vigil was held at Cedar Ridge Community Church. Nearly a hundred people showed up, standing shoulderto-shoulder in the parking lot as Pastor Gerald Matthews led them in prayer.

Linda Turner stood at the front, her face pale and drawn, clutching a photograph of her parents taken the previous Christmas. Her younger brother, Matthew, stood beside her, his hands shoved deep into his coat pockets, his jaw tight. He’d driven up from Moscow the day after the disappearance, and he hadn’t left since. He looked older than 19, older and tired, like someone carrying a weight they couldn’t put down.

After the vigil, Sheriff Hughes asked both siblings to come down to the station for formal interviews. It was a courtesy more than anything else, a way to rule them out, to document their whereabouts, to check for any detail that might have been overlooked in the chaos of the first few days. Linda went first.

She sat across from Hughes in the cramped interview room, her hands folded tightly in her lap. Hughes kept his voice gentle, his question straight forward. When did you last see your parents, Linda? Two weekends ago, she said. October 6th. I drove up for Sunday dinner. We had pot roast. Mama made apple pie. How did they seem? Normal. Happy.

Daddy talked about winterizing the house. Mama showed me her rose bushes. She was worried about the frost. And you didn’t notice anything unusual? Any tension? Any visitors? Linda shook her head. No, everything was fine. Hughes made a note. Did they mention any plans? Anyone they were expecting? No. Her voice cracked slightly.

They were just themselves. Matthew’s interview was shorter, but no less unsettling. He sat stiffly in the chair, his eyes fixed on the table, answering in clipped, careful sentences. I was home the first weekend of October, he said. I left on Sunday afternoon to get back to school. I called them on Wednesday. Mama answered. She said everything was fine.

Did you speak to your father briefly? He was in the garage. Said he had work to do and that was the last time you spoke to either of them. Matthew hesitated just for a moment. Yes. Hughes watched him closely. There was something guarded in the young man’s posture. something that didn’t quite sit right.

But when Hughes pressed gently, professionally, Matthew’s answers didn’t change. He had been at school. He had attended classes. He had an alibi, witnesses, a paper trail. There was nothing to suggest he knew anything more than what he’d already said. Still, Hughes made a note in his log. Subject appeared evasive. Follow up if necessary.

As October bled into November, the searches stopped altogether. The volunteers returned to their lives. The dogs never came back. The torn handkerchief remained in an evidence locker, a fragment of something that meant nothing.

Sheriff Hughes continued to field calls, tips, theories, sightings that led nowhere. A truck driver claimed he’d seen a couple matching the Turner’s description at a rest stop near Kurdelene. A woman in Spokane swore she’d seen Rebecca at a grocery store. Both leads evaporated under scrutiny. The town, meanwhile, began to forget. Not intentionally, not cruy. But life moved on.

The mill kept running. Kids went to school. Thanksgiving came and went. Then Christmas. The Turner’s farmhouse stood empty on old pine road, its windows dark, the yard slowly overtaken by weeds and wild grass. Occasionally, someone would drive past and glance at it. A quick look, a brief flicker of memory, but fewer people talked about it. The story had lost its urgency.

It had become background noise, a sad footnote in the town’s history. On November 2nd, 1973, Sheriff Hughes officially reclassified the case. He sat at his desk late that evening, the office empty except for the hum of the space heater in the corner, and typed the update on a manual Underwood typewriter. Each keystroke deliberate and final case status update.

Turner James Rebecca missing persons reclassified to unexplained disappearance. No evidence of foul play. No evidence of voluntary departure, no viable leads, case to remain open, pending new information. He pulled the paper from the roller and placed it in the case file, which by now had grown to nearly 40 pages, witness statements, search reports, lab results that confirmed nothing. Hughes closed the file and slid it into the cabinet marked active, unsolved.

He locked the drawer and pocketed the key. By spring of 1974, the case was quietly shelved. The file was moved from active to cold, placed on a shelf in the records room alongside a dozen other mysteries that had never been solved. Lost hunters, runaway teenagers, drifters who vanished into the Idaho wilderness and were never seen again. Cedar Ridge moved on.

The Turners became a ghost story. The kind of thing people mentioned when they were feeling nostalgic or morbid, usually after a few drinks. Remember the couple who just disappeared? No trace, nothing. Just gone. And then the conversation would shift to something else, someone’s daughter getting married, a new manager at the mill, the upcoming harvest.

For 44 years, the farmhouse on Old Pine Road stood silent, its seller floor undisturbed. its secrets buried beneath concrete and time, and no one thought to look down. 45 years later, the farmhouse on Old Pine Road was finally coming back to life. It was early March 2018, and the morning sun filtered weakly through the bare windows of what had once been the Turner family home.

Inside, the air smelled of sawdust and fresh paint, mingled with the musty odor of decadesl long abandonment. Dust moes drifted through pale shafts of light as Ethan and Clare Morris moved through the rooms, their footsteps echoing on stripped floorboards. They were young, early 30s, full of the kind of optimism that comes with firsttime home ownership and HGTV renovation dreams.

The house had been a steal at auction. Its history more curiosity than deterrent. “It just needs love,” Clare had said when they first walked through it 6 weeks earlier. her hand trailing along the peeling wallpaper in the hallway. Good bones, character. Ethan had agreed, though privately he wondered if character was just real estate code for haunted. But the price was right.

The land was beautiful, and Cedar Ridge, now a town of nearly 6,000, bolstered by telecomuters and retirees seeking mountain quiet, was exactly the kind of place they’d been searching for. By mid-March, the upstairs was nearly finished. New drywall, fresh paint, and soft grays and whites, refinished hardwood floors that gleamed under the pendant lights Clare had ordered online.

The kitchen had been gutted and rebuilt. The living room, once dim and closed in, now open to the backyard through new French doors. It was starting to feel like a home. But the cellar was another story.

The cellar had been left for last, partly because it was damp and uninviting, partly because neither Ethan nor Clare was eager to spend time down there. The old field stone walls were crumbling in places, and the air had a persistent chill that no amount of dehumidifying seemed to fix. The concrete floor, poured in uneven sections over the decades, was cracked and stained. Ethan had hired a local contractor, Kyle Davis, to handle the seller renovation.

tear out the old floor, install proper drainage, pour a new slab, and frame out a potential workshop space. Kyle was a broad-shouldered man in his late 40s with hands like Catcher’s mitts, and a reputation for reliable work. He’d grown up in Cedar Ridge, and when Ethan mentioned the address, Kyle had paused, then nodded slowly. “The Turner place,” he’d said.

“Hell of a story. You know about it. Everyone does.” or did. It was a long time ago. On the morning of March 14th, Kyle arrived at the house just after 7. His truck loaded with tools and a rented concrete saw. Ethan met him at the door with a thermos of coffee. Starting with the seller today? Ethan asked. That’s the plan. Get that old slab out.

See what we’re working with underneath. Clare appeared in the doorway pulling on a jacket. I’m heading to Lewon for paint samples. You need anything? We’re good, Ethan said. He kissed her cheek and watched her drive off, then turned back to Kyle. You need a hand down there? Nah, I got it. Loud work, though. You might want to stay upstairs.

Ethan didn’t argue. Kyle descended the creaking cellar stairs, flipped on the work lights he’d rigged the day before, and surveyed the floor. The plan was straightforward. cut the concrete into manageable sections, break it up with a jackhammer, haul it out piece by piece. He’d done it a hundred times.

He pulled on his safety glasses, started the gas-powered concrete saw, and guided the spinning diamond blade toward the center of the floor. The saw bit into the concrete with a high grinding shriek. Dust billowed up in thick clouds, and Kyle leaned into the work, following a chalk line he’d marked earlier. The blade chewed through the old concrete smoothly for the first few feet. Then suddenly it stuttered. The motor winded.

The blade caught on something and kicked back violently, nearly jerking the saw from Kyle’s hands. He killed the engine and stepped back, breathing hard. The hell? He knelt down and brushed away the concrete dust. The cut was clean for about 3 ft. Then it stopped abruptly. He ran his gloved hand along the groove and felt something solid beneath the surface.

Not rebar, not stone, something else. He grabbed a pry bar and chipped carefully at the edge of the concrete. A chunk broke away, revealing a sliver of dark, rotted wood. Kyle frowned. He pried further, breaking off more concrete and jagged pieces until a section of splintered plank was exposed. Beneath it, he saw fabric.

old, discolored, disintegrating, and something pale and smooth that made his stomach drop. Bone. He stood up quickly, his pulse hammering in his ears. For a long moment, he just stared at the hole in the floor, his mind racing. Then he turned and climbed the stairs two at a time. Ethan. His voice was sharp, breathless. Ethan appeared in the hallway, startled. What’s wrong? You need to call the police right now.

What? Why? Kyle’s face was pale. There’s something down there under the floor. Within 30 minutes, Cedar Ridge police had cordoned off the property. Two patrol cars sat in the gravel drive, their lights flashing silently in the midday sun. By noon, the Idaho State Police had arrived, followed by a forensic team from Boise.

The farmhouse, so recently a symbol of renewal, had become a crime scene. Detective Sarah Miller arrived just after 1:00. She was 45, composed with sharp eyes and a methodical demeanor honed by 15 years in law enforcement and the last five heading Idaho’s cold case unit. She’d driven up from Boise as soon as the call came through.

And now she stood at the top of the cellar stairs, looking down at the growing excavation site below. The forensic team worked in near silence, their movements careful and deliberate. Flood lights had been set up, casting harsh white light across the cellar floor. The concrete had been removed in a 6×8 ft section, revealing a shallow grave dug into the packed earth beneath.

Two skeletons lay side by side, partially wrapped in the tattered remains of canvas tarps. The bones were brown with age, some still partially articulated, others scattered by time and decay. Miller descended the stairs slowly, pulling on latex gloves. The lead forensic technician, a woman named Dr. Lena Ortiz, glanced up as she approached. “What have we got?” Miller asked. “Two bodies,” Ortiz said, her voice calm and clinical.

adult, one male, one female. Based on pelvic structure, they’ve been here a long time, decades at least. We’re seeing significant decomposition, but the bones are in reasonably good condition given the environment. Cause of death. Ortiz gestured toward the male skeleton. Gunshot trauma.

You can see the entry fracture here on the fifth rib. The bullet likely perforated the chest cavity. We recovered a fragment near the spine. She moved to the second skeleton. Female victim also shows evidence of trauma, possible gunshot wound to the upper torso. We’ll know more after a full examination. Miller crouched beside the grave, her eyes scanning the remains.

Near the male skeleton’s right hand, something metallic gleamed under the flood lights. One of the techs carefully extracted it with tweezers. A revolver badly rusted, its barrel fractured, the wooden grip cracked and discolored. Colt 38, the tech said, “Looks like it was fired and left here.” Miller’s gaze shifted to the female skeleton. Near the left hand, half buried in the dirt, was a thin gold band.

Another technician lifted it carefully, turning it toward the light. Engraved on the inside, barely legible through the tarnish, were two letters. RT Rebecca Turner. Miller stood slowly, her mind already working through the implications. She turned to Ortiz. How long until we can get DNA? We’ll extract samples from the teeth tonight if we’re lucky. 48 hours for preliminary results. Miller nodded.

She climbed back up the stairs and stepped outside where Ethan Moore stood near the porch. his face ashen, his hands shaking slightly as he held a cup of coffee he hadn’t touched. “Mr. Morris,” Miller said gently. “I know this is a shock. We’re going to need to keep the property secured for a few days while we process the scene. I’ll make sure you’re updated as we learn more.

” Ethan nodded mutely, unable to form words. Miller walked to her car and pulled out her phone. She dialed the number for the Boise Crime Lab and waited. “It’s Miller,” she said when the line connected. “I need you to pull everything we have on a 1973 missing person’s case. James and Rebecca Turner, Cedar Ridge.

” She paused, looking back at the farmhouse, its windows glowing softly in the fading afternoon light. “I think we just found them.” By 6:00 that evening, news vans from Lewon and Boise had descended on Cedar Ridge. Reporters stood on Old Pine Road, their cameras trained on the farmhouse as the sun dipped below the mountains.

At 8, the local NBC affiliate ran a breaking news banner across the bottom of the screen. Human remains found beneath Cedar Ridge Farmhouse. The story spread quickly online across social media through the bars and diners of Northern Idaho. For the first time in 45 years, people were talking about the Turners again. And this time, they weren’t going to disappear.

The Idaho State Forensic Laboratory occupied a nondescript brick building on the outskirts of Boise. Tucked between a credit union and a veterinary clinic. Inside, beneath fluorescent lights that never dimmed, the dead spoken whispers through bone and tissue through trace evidence invisible to the naked eye.

through the patient painstaking work of scientists who treated every case like a puzzle that deserved solving. On the morning of March 16th, 2018, the remains from the Turner farmhouse arrived in sealed evidence bags, logged and cataloged with the clinical precision that governed every inch of the lab. Dr. Lena Ortiz, the lead forensic anthropologist, cleared her schedule and assembled her team.

By noon, the skeletons had been carefully laid out on stainless steel examination tables in the main autopsy suite. Each bone photographed, measured, and documented. Detective Sarah Miller arrived at 2:00, her boots echoing in the sterile hallway as she made her way to the observation room. She’d spent the morning at her office in Boise, pulling the original 1973 case file from the state archives, a thin folder containing Sheriff Hughes’s reports, witness statements, search records, and a handful of black and white photographs of the Turner farmhouse as it had looked 45 years ago. The file had been marked

cold, unsolved, and filed away in a banker’s box that hadn’t been opened in decades. Now standing behind the glass partition that separated the observation room from the examination suite, Miller watched as Dr. Ortiz worked with quiet efficiency, her gloved hands moving across the skeletal remains like a pianist reading sheet music.

Miller was 45, though she carried herself with the stillness of someone older, someone who’d learned that patience and observation were worth more than speed. She’d been with the Idaho State Police for 15 years, the last five devoted entirely to cold cases. She had a reputation for being thorough, methodical, and perhaps most importantly, impossible to discourage.

“Other detectives moved on when cases went cold.” Miller leaned in. The intercom crackled. “Detective, you can come in if you’d like,” Ortiz said, not looking up from her work. Miller pushed through the door, pulling on a pair of latex gloves and a surgical mask. The air in the suite was cool and faintly antiseptic.

She approached the examination tables slowly, her eyes moving over the remains with professional detachment. What can you tell me? Miller asked. Ortiz straightened, rolling her shoulders. Male victim, age 50 to 55 at time of death. Height approximately 5’9. Evidence of healed fractures consistent with manual labor. Right radius, left clavicle. Good dental work. No sign of serious illness.

She gestured to the rib cage. Cause of death: gunshot wound to the chest. Single entry point here between the fourth and fifth ribs. The bullet perforated the thoracic cavity and lodged near the spine. We recovered the fragment during the initial excavation. She moved to the second table. Female victim age 45 to 50. Height approximately 5’4.

Also evidence of healed fractures. Left ulna consistent with a fall or defensive injury years before death. Dental work similar to the male. Ortiz pointed to the upper torso. Gunshot wound here likely to the chest or upper abdomen. The bullet passed through.

So we don’t have a fragment but the angle and trajectory are consistent with close-range fire. How close? Less than 6 ft, possibly less than three. Miller absorbed this quietly. Time of death, decades, the degree of decomposition, the condition of the fabric and surrounding soil. I’d estimate 40 to 50 years, maybe longer. We’ll have a tighter window once we run isotope analysis on the bone collagen and the weapon.

Ortiz walked to a side table where the rusted Colt revolver had been placed in a clear evidence tray. Colt 38 special manufactured sometimes in the 1960s based on the serial number. It was fired at least twice. You can see residue in the barrel and chamber. The grip shows significant degradation, but we were able to recover trace organic material. Miller leaned closer.

DNA. Possibly. We’ve sent samples to the genetics lab. It’ll take a few days. Miller nodded. What about the victims? Can we confirm identity? We extracted DNA from the teeth of both victims this morning. Results should be back within 48 hours, but based on the physical profile and the location, I’d say we’re looking at James and Rebecca Turner.

Good. Miller stepped back, her mind already moving through the next steps. I want everything cross- referenced, dental records, medical history, anything that can give us a positive ID, and I want that revolver processed for prints, DNA, anything. Already on it. 2 days later, the DNA results came back.

Miller was at her desk in the cold case unit offices when her phone buzzed. She picked it up on the first ring. Miller, it’s Ortiz. We’ve got confirmation. The male victim is James Turner. 99.97% matched to a DNA sample from his son, Matthew Turner, on file with the National Database. Female victim is Rebecca Turner. 99.

95% matched to a sample from their daughter, Linda Harrington, formerly Turner. Miller closed her eyes briefly, letting the confirmation settle. So, it’s them. No question. and the revolver. Ortiz hesitated. That’s where it gets interesting. We recovered two partial DNA profiles from organic material on the grip. One is male. It matches Matthew Turner with 99.96% certainty.

The second is female, degraded, but usable. It’s a familiar match to Linda Harrington. Miller sat up straighter. Both siblings. Both siblings. For a long moment, Miller said nothing. She stared at the open case file on her desk, the faded photographs, the handwritten reports, the name Turner printed neatly on the tab. Then she reached for her notepad and started writing.

Get me everything you’ve got on Matthew Turner and Linda Harrington. Current addresses, employment, criminal records, financials. I want to know where they were in October 1973, and I want to know where they are now. Copy that. Miller hung up and leaned back in her chair, her mind racing.

She opened the 1973 case file and flipped to the witness statements. There, near the back, were two brief interviews, one with Linda Turner, age 24, and one with Matthew Turner, age 19. Both had been questioned by Sheriff Hughes in the days following the disappearance. Both had provided alibis. Both had been cleared.

But now, 45 years later, their DNA was on the murder weapon. Miller picked up her phone again and dialed the evidence unit. This is Miller. I need a full re-examination of all preserved items from the 1973 Turner case. Photographs, clothing, anything in storage. I want it processed with current forensic standards, DNA, trace evidence, everything.

She hung up and stood, walking to the window that overlooked the parking lot. Outside, the afternoon sun filtered through thin clouds, casting long shadows across the asphalt. Somewhere out there, Matthew Turner and Linda Harrington were living their lives, working, eating, sleeping, unaware that the past had finally caught up to them.

Miller pulled the original case file toward her and opened it to the last page where Sheriff Hughes had written in careful script, “No signs of departure. Cause of absence unknown.” She picked up a pen and beneath Hughes’s words, wrote a single line in her own neat handwriting. Victims never left the residence, buried in cellar beneath concrete. Homicide confirmed. Then she closed the file and reached for her coat.

That evening, Miller sat alone in her office long after the rest of the unit had gone home. The only light came from the desk lamp in the glow of her computer screen where she’d been reviewing old county records, property deeds, tax filling, vehicles registration.

She cross referenced them with phone logs, college enrollment records, anything that could place Matthew and Linda Turner in Cedar Ridge on the night of October 12th, 1973. A pattern was beginning to emerge. Small inconsistencies, gaps in the timeline. A hardware store receipt from Lewon dated October 10th, 1973, 2 days before the disappearance, showing a purchase of 38 caliber ammunition under Matthew Turner’s name.

Miller printed the receipt and added it to the growing stack of documents on her desk. Then she leaned back in her chair, staring at the ceiling, and spoke aloud to the empty room. After 45 years, they never left the house. She sat forward and opened a new document on her computer. At the top, she typed arrest warrants pending.

Beneath it, two names, Matthew Turner, Linda Harrington. Then she saved the file, turned off the lamp, and walked out into the night. The evidence had spoken. Now it was time to listen. Matthew Turner lived in a modest ranchstyle house on the outskirts of Eugene, Oregon in a quiet neighborhood where lawns were neatly mowed and American flags hung from porches.

He was 63 years old, retired from a career in municipal engineering, and by all accounts lived an unremarkable life. He had never married, had no children, and kept mostly to himself. The kind of neighbor people waved to but didn’t really know. On the morning of March 22nd, 2018, Detective Sarah Miller and an Oregon State Police detective named Ron Vasquez pulled into his driveway in an unmarked sedan. The sun was bright, the air crisp with early spring.

Matthew’s garage door was open, revealing a workbench cluttered with hand tools and a half-restored motorcycle. Matthew appeared in the doorway before they could knock, wiping his hands on a shop rag. He was tall, lean, with thinning gray hair and wire- rimmed glasses. His expression was neutral, not surprised, not defensive, just waiting.

Matthew Turner, Miller asked, holding up her badge. “Yes, I’m Detective Sarah Miller with the Idaho State Police.” “This is Detective Vasquez. We’d like to ask you a few questions about your parents, James and Rebecca Turner.” Matthew didn’t flinch. He nodded slowly, folded the rag, and set it on a small table by the door. I figured someone would come eventually. You found them. We did.

Come in. He led them into a small, tidy living room. The furniture was plain, a brown sofa, a recliner, a coffee table with a few engineering magazines stacked neatly on top. The walls were bare except for a single framed photograph of a mountain landscape. No family photos, no personal momentos. Matthew sat in the recliner, his hands resting on the armrests.

Miller and Vasquez took the sofa. Miller pulled out a notebook and pen, her movements deliberate and unhurried. Mr. Turner, we’re reopening the investigation into your parents’ disappearance. We’ve confirmed that the remains found beneath the farmhouse are James and Rebecca Turner. We believe they were killed on or around October 12th, 1973.

Matthew nodded. I assumed as much. Can you tell me where you were that night? I was at school, University of Idaho, Moscow. I’d left home on Sunday, October 7th, to start the fall semester. I didn’t come back until after the police called Linda. Miller made a note. And when did you last see your parents? That Sunday, October 7th.

I had lunch with them before I drove back to campus. How did they seem? Normal. Dad was talking about fixing something in the cellar. A leaky pipe, I think. Mom was worried about her garden before the first frost. It was just a regular Sunday. Did you call them after you left? Matthew hesitated just for a fraction of a second.

I called on Wednesday, October 10th. Mom answered. We talked for maybe 5 minutes. Everything was fine. Miller watched him carefully. His voice was calm, measured, almost rehearsed. And you didn’t return to Cedar Ridge until after they were reported missing. That’s right. Linda called me on Sunday the 14th. I drove up that afternoon. Vasquez leaned forward slightly.

Did you notice anything unusual when you got there? Anything out of place? No. The house looked normal, locked up like Linda said. I searched the property with her, but we didn’t find anything. Miller flipped a page in her notebook. Mr. Turner, do you own any firearms? No. Did your father? He had a revolver, a cold 38.

Kept it in the bedroom closet. Do you know what happened to it? Matthew’s expression didn’t change. I assume it disappeared with them. Miller let the silence stretch. Then she said, “We recovered a firearm from the grave site, a cult 38. We believe it was used to kill your parents.” Matthew’s jaw tightened almost imperceptibly, but his voice remained steady. “I see.

We also recovered DNA from the weapon,” Miller continued. “Would you be willing to provide a sample for comparison?” “Of course, whatever you need.” Miller made another note. her pen moving across the page in slow, deliberate strokes. One more thing. Do you remember purchasing ammunition in Lewon on October 10th, 1973? For the first time, Matthew’s composure cracked, his eyes narrowed slightly, his fingers curling against the armrest.

I don’t recall. The receipt shows 38 caliber rounds purchased at Barlo Hardware. Your name is on file. Matthew stared at her for a long moment, then looked away. I might have. I used to go target shooting. It was a long time ago. Two days before your parents disappeared. Like I said, it was a long time ago. Miller closed her notebook and stood.

We appreciate your cooperation, Mr. Turner. We’ll be in touch. Matthew didn’t get up. He sat in the recliner, his hands still gripping the armrests, his eyes fixed on the blank wall across from him. As Miller and Vasquez walked back to their car, Vasquez glanced over his shoulder. He’s lying. I know, Miller said.

Linda Harrington lived in Spokane, Washington, in a small craftsmanstyle house with a well-tended garden and windchimes hanging from the front porch. She was 68, a widow, her husband having passed away 3 years earlier from complications of diabetes. She had two grown children, both living out of state, and spent most of her days volunteering at the public library and attending her church’s Bible study group.

When Miller and a Spokane PD detective named Amy Chen arrived on the afternoon of March 23rd, Linda answered the door with a kind, weary smile. She was small, gray-haired, dressed in a cardigan and slacks. Her eyes were soft but tired, the kind of eyes that had seen too much and decided long ago to stop looking. “Mrs. Harrington,” Miller said. “Yes, I’m Detective Sarah Miller. This is Detective Chen.

We’d like to talk to you about your parents.” Linda’s smile faded. She nodded and stepped aside. I’ve been expecting you. They sat in her living room, which was warm and cluttered with photographs, grandchildren, vacation snapshots, her late husband in a navy uniform. On the mantle, a single black and white photo showed a young couple standing in front of a farmhouse, James and Rebecca Turner. Linda folded her hands in her lap and looked at Miller with quiet resignation.

“You found them?” “We did?” Linda closed her eyes briefly. “I always knew someone would eventually. I just didn’t think it would take this long. Miller leaned forward slightly. Mrs. Harrington, can you tell me what you remember about October 1973? Linda took a deep breath. I remember everything.

I remember getting the call from Agnes Crowley. I remember driving to the house and finding the doors locked. I remember calling the police and waiting for them to arrive. I remember searching for weeks hoping they’d just show up. When did you last see your parents? Two weekends before. October 6th, I think. I came up for Sunday dinner. Everything was fine.

And your brother? Linda’s expression tightened. Matthew was home that weekend, too. He left on Sunday. Did you speak to him after that? Once, maybe twice. We weren’t close. Are you close now? Linda looked down at her hands. No. Miller made a note. Mrs. Harrington, we’ve recovered forensic evidence from the crime scene, DNA evidence.

We’re in the process of comparing it to family members. Linda nodded slowly. I understand. Would you be willing to provide a sample? Of course. Miller studied her carefully. Do you have any idea what happened to your parents that night? Linda’s eyes welled up, but she didn’t cry. She looked at Miller with a strange mixture of grief and something else. Something harder to name.

I stopped asking myself that question a long time ago, detective. It was easier that way. Easier than what? Linda didn’t answer. She stood and walked to the window, looking out at the garden where early crocuses were beginning to bloom. I let the past go, she said quietly. I had to for my family, for my children. You can’t live your whole life haunted by something you can’t change. Miller stood as well. Mrs.

Harrington, if you know something, anything, now is the time to tell us. Linda turned, her face pale. I don’t know anything, detective. I just know my parents are gone and no amount of digging is going to bring them back. Back in Boise, Miller spread the case files across her desk. Old reports from 1973 alongside the new forensic data.

She compared Matthew’s statement from 2018 with the one he’d given Sheriff Hughes 45 years earlier. The details matched almost perfectly. Too perfectly. She cross- referenced Linda’s interviews, also consistent, also too polished. Then she found it.

Buried in the old case file was a neighbor’s statement, Carl Jensen, who’d driven past the Turner house on the night of October 12th around 9:00. He’d reported seeing the lights on but no activity. But there was a second statement taken 3 days later in which Jensen mentioned seeing a car parked on the side of the road near the Turner property. A dark sedan, he thought, though he couldn’t be sure. Miller flipped to the vehicle registration records.

In October 1973, Matthew Turner had been driving a 1969 Ford Galaxy. Dark blue. She picked up her phone and called the genetics lab. This is Miller. I need the DNA results from the Turner evidence expedited, specifically the revolver. The lab tech hesitated. We’re still processing. I need it today. 12 hours later, the results came through.

Miller read the report three times. Her pulse steady, her mind sharp. The DNA profile recovered from the grip of the Colt 38 revolver matched Matthew Turner with 99.96% certainty. Miller set the report down, picked up her phone, and dialed the prosecutor’s office. It’s Miller, she said. I need an arrest warrant.

The morning of June 4th, 2018, arrived soft and cool in Eugene, Oregon. The sun had just cleared the hills to the east, casting pale gold light across quiet suburban streets. Somewhere down the block, a lawn mower hummed steadily, the sound drifting through open windows and mingling with bird song.

It was the kind of morning that felt ageless, ordinary, the kind where nothing important was supposed to happen. Matthew Turner was in his kitchen pouring his second cup of coffee when he saw the cars pull up. Three unmarked sedans moving in formation, followed by two Oregon State Police cruisers.

They stopped in front of his house with calm precision, doors opening in near synchrony. Men and women in tactical vests emerged, some wearing jackets emlazed with FBI, others with OSP. Detective Sarah Miller stepped out of the lead vehicle, her expression unreadable. Matthew set his coffee cup down slowly. His hand didn’t shake. He walked to the front window and stood there, watching as the officers moved up his driveway in a quiet, coordinated line.

He’d known this was coming. He’d known since the moment Miller had sat across from him in March and asked about the ammunition. The doorbell rang. He walked to the door and opened it before they could knock again. Miller stood on the threshold, flanked by two federal agents.

Behind her, more officers fanned out across the lawn, securing the perimeter. The hum of the distant lawn mower continued, oblivious. “Matthew Turner,” Miller said, her voice steady and formal. “You are under arrest for the murders of James and Rebecca Turner.” Matthew’s face went pale, but he didn’t resist. He didn’t speak.

He simply stepped back, turned around, and placed his hands behind his back. One of the agents moved forward with handcuffs, the metal clicking softly in the morning stillness. You have the right to remain silent, Miller began, reciting the Miranda warning as the cuffs tightened around Matthew’s wrists.

Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. Matthew listened, his eyes fixed on the floor, his jaw clenched. When Miller finished, she asked, “Do you understand these rights?” Yes, he said quietly. They led him out to the waiting car. A few neighbors had emerged onto their porches, drawn by the commotion, watching in stunned silence as Matthew Turner, their quiet, unassuming neighbor, was placed in the back of an unmarked sedan.

The door closed with a heavy thud, and the convoy pulled away, leaving the street empty and still once more. The lawn mower continued its steady hum. October 12th, 1973. 9:47 p.m. The argument had started over nothing. Or at least that’s what Matthew would tell himself later in the long, sleepless nights that followed.

Something about money, about responsibilities, about Matthew’s plans after college. Plans his father didn’t approve of, didn’t understand. They’d been in the cellar. James had been working on the leaky pipe, his hands dark with grease, his voice sharp with frustration. Matthew had come down to help, but the conversation had turned. The way conversations sometimes do when old resentments simmer just beneath the surface.

“You think you’re better than this,” James had said, gesturing around the dim cellar. “Better than the mill. Better than this town.” “I didn’t say that. You don’t have to.” The words escalated louder, sharper. Matthew’s hands curled into fists at his sides, his pulse pounding in his ears. And then James had turned his back, dismissive, done with the conversation, and something in Matthew snapped.

He’d gone upstairs to his old room to the closet where he knew his father kept the revolver. When he came back down, the gun felt heavier than he’d expected. James was still at the workbench, muttering to himself, unaware. Matthew’s hand shook as he raised the weapon. “Dad!” James turned.

The shot was deafening in the enclosed space, a crack that seemed to split the air itself. James staggered backward, his hands going to his chest, his eyes wide open and incomprehension. He opened his mouth to speak, but no words came. He crumpled to the dirt floor, gasping, blood spreading dark across his shirt.

Matthew stood frozen, the gun still in his hand, his mind a white roar of panic. Then he heard footsteps on the stairs. James. Matthew. What was that? Rebecca’s voice, worried, hurried. She appeared at the bottom of the stairs, her eyes finding her husband first, his body on the floor, the blood, and then her son standing over him with the revolver.

“Matthew,” she whispered, her voice breaking. “What did you do?” She took a step toward James, and Matthew raised the gun again, his hand trembling violently. “Mom, don’t!” she screamed. The second shot cut her scream short. Rebecca fell without a sound, her body crumpling beside her husband’s, her eyes still open, staring at nothing.

For a long time, Matthew just stood there, the gun hanging at his side, the smell of gunpowder thick in the air. Then slowly, the panic gave way to something colder. Calculation, survival. He couldn’t undo this, but he could hide it. 3 days after Matthew’s arrest, Linda Harrington was taken into custody at her home in Spokane. She didn’t resist. She’d been expecting it. The charges were different.

Conspiracy to conceal a crime, obstruction of justice, aiding after the fact, not murder, but enough. Detective Miller sat across from Linda in a small interview room at the Spokane County Jail, a digital recorder on the table between them. Linda looked smaller somehow, diminished, her hands folded tightly in her lap. “Mrs.

Harrington,” Miller said gently, “I need you to tell me what happened.” “All of it.” Linda stared at the table for a long time. Then quietly, she began to speak. He called me. Sunday night, October 14th, late, he was panicking. He told me they were gone, that something terrible had happened.

He didn’t say what, not then, but I knew. I could hear it in his voice. What did he ask you to do? Linda’s eyes filled with tears. He asked me to come to the house before the police did. He said he needed my help. He said he couldn’t do it alone. And you went. I went. Her voice cracked. I cleaned the kitchen. I locked the doors from the inside. I made it look like they just left.

I didn’t know what else to do. He was my brother, my baby brother, and he was so scared. Miller’s voice remained calm, measured. Did he tell you what happened that night? Linda shook her head. Not then, not for years, but I knew. Deep down, I always knew. And you said nothing. I said nothing. Linda looked up, her face stre with tears. I told myself I was protecting the family, protecting his future. But really, I was just a coward.

By midJune, Cedar Ridge was once again under siege. Not by volunteers searching the woods, but by news vans and reporters crowding Main Street, their cameras trained on the old farmhouse on Old Pine Road. The story had gone national. Cold case solved. After 45 years, siblings arrested in parents’ murder. The headlines were everywhere.

In the diners and churches, at the mill and the post office, people who had once known the Turners or thought they had, struggled to reconcile the past with the present. Matthew and Linda, the grieving children who’d searched for their parents, who’d lit candles at vigils, who’d carried the weight of that loss for decades, were now revealed as something else entirely.

“I can’t believe it,” Agnes Crowley said to a reporter outside the community church. She was 89 now, her voice thin and unsteady. I watched those children grow up. I never thought. She trailed off, shaking her head. On June 18th, Detective Sarah Miller held a press conference in Boise. The room was packed, reporters, cameras, the harsh glare of lights.

She stood at the podium, calm and composed, and read a prepared statement. On the night of October 12th, 1973, James and Rebecca Turner were killed in the cellar of their home by their son, Matthew Turner. Their bodies were buried beneath the concrete floor, where they remained undiscovered for 45 years. Matthew Turner returned to his college campus the following morning and resumed his life as if nothing had happened.

His sister, Linda Harrington, aided in concealing the crime by staging the scene to appear as a disappearance. She paused, looking directly into the cameras. For 45 years, this case haunted Cedar Ridge. Families grieved. Neighbors wondered. Investigators searched. And all the while, the answers were buried beneath a floor that no one thought to look under.

Miller’s voice didn’t rise, didn’t waver, but there was something sharp beneath her words, something that cut through the noise. He went back to school the next morning, she said quietly, and no one ever asked why. The room fell silent. Miller stepped away from the podium and walked out, leaving the questions unanswered, the cameras still rolling, the ghosts of Cedar Ridge finally laid to rest. The interview room at the Ada County Jail was small and colorless.

Gray walls, gray table, gray chairs bolted to the floor. A single fluorescent panel hummed overhead, casting everything in flat sterile light. The air smelled faintly of disinfectant and stale coffee. A camera mounted in the corner recorded everything, its red light blinking steadily like a mechanical heartbeat.

Matthew Turner sat on one side of the table, his hands folded in front of him, his orange jumpsuit hanging loose on his thin frame. He’d been in custody for 2 weeks. His face was gaunt, unshaven, his eyes shadowed with sleeplessness.

Across from him sat Detective Sarah Miller, a legal pad open in front of her, a pen resting in her hand. To her right, a digital recorder sat on the table, its display glowing softly. They’d been at this for 3 hours. Miller had started gently, background questions, establishing timeline, letting Matthew tell his version of events. He’d been evasive at first, repeating the same story he’d told for 45 years. He’d left for school.

He’d called home midweek. He hadn’t known anything was wrong until Linda called him. His voice had been steady, almost mechanical, as if he’d rehearsed it so many times the words had lost all meaning. But Miller was patient. She had time, and more importantly, she had evidence. Matthew,” she said now, her voice calm.

“We’ve been over this multiple times, and every time your story stays the same. Perfectly the same.” Matthew didn’t respond. He stared at his hands. “The problem,” Miller continued, “is that the evidence doesn’t match your story. Your DNA is on the murder weapon. The ammunition you purchased 2 days before your parents died matches the rounds fired in that cellar.

and we have a witness who saw your car near the property the night they were killed. Matthew’s jaw tightened, but he said nothing. Miller leaned forward slightly. I’ve been doing this a long time, Matthew, and I’ve learned that people hold on to lies for two reasons. Either they’re protecting someone else or they’re protecting themselves. Which one is it for you? Silence.

Miller let it stretch. Then she reached into a folder and pulled out a photograph. A closeup of the rusted Colt revolver laid out on an evidence tray. She placed it in front of Matthew. This is your father’s gun. The one you said disappeared with them. She tapped the photo.

We found it buried with their bodies. Your DNA is on the grip. Your fingerprints, partial but identifiable, are on the trigger guard. Matthew stared at the photo, his breathing shallow. I know you were there, Matthew. I know you pulled the trigger. What I don’t know is why. For a long moment, nothing.

Then, almost imperceptibly, Matthew’s shoulders began to shake. His hands curled into fists, and a sound escaped his throat. Half breath, half sobb. When he finally spoke, his voice was so quiet, Miller had to lean in to hear it. It wasn’t supposed to happen. Miller didn’t move. She barely breathed. Tell me. October 12th, 1973. 9:40 p.m.

Matthew stood at the top of the cellar stairs, his father’s revolver heavy in his hand. Below, he could hear James muttering to himself, the clang of a wrench against pipe. The argument from earlier still burned in Matthew’s chest. His father’s dismissive tone, the way he’d waved off Matthew’s plans like they were childish fantasies.

You think you’re better than this? Matthew descended the stairs slowly, each step deliberate. At the bottom, James looked up, surprised. Matthew, what are you? His eyes fell to the gun. What the hell are you doing with that? I just want you to listen, Matthew said, his voice shaking. Just for once, listen to me. James straightened, his face darkening. Put that down now. No, Matthew.

You never listen. The words burst out of him, raw and jagged. You never take me seriously. You think I’m just going to come back here, work at the mill, live the same small life you did. But I’m not. I’m not you. James took a step forward. Put the gun down. Matthew Han trembled. Stay back. You don’t even know how to. James reached for the weapon.

The shot was an accident. At least that’s what Matthew would tell himself later in the endless hours of darkness that followed. His finger jerked on the trigger. The gun kicked back. The noise was impossibly loud. a crack that echoed off the stone walls and seemed to shatter the world.

James staggered, his hand going to his chest. He looked down at the blood spreading across his shirt, then up at his son, his expression one of utter disbelief. “Matthew,” he whispered. Then he collapsed. “I didn’t mean to,” Matthew said now, his voice breaking. “I swear to God, I didn’t mean to. I just wanted him to listen. I just wanted him to see me.

Miller’s expression didn’t change, but something shifted in her eyes. Not sympathy exactly, but a recognition of the fragility of the moment. What happened next? Matthew’s hands were shaking. I heard her on the stairs, my mother. She was calling down, asking what the noise was, and I I couldn’t move. I couldn’t think.

I just stood there. Rebecca appeared at the bottom of the stairs, her face already pale with fear. She saw James first, his body on the floor, the blood pooling beneath him, and let out a choked gasp. “James!” she rushed forward, dropping to her knees beside him.

Her hands fluttered over his chest, trying to stem the bleeding, her voice rising in panic. “Oh God! Oh god!” Then she looked up and saw Matthew standing there, the gun still in his hand. “Matthew,” she breathed, her voice small and broken. What did you do? She started to stand, her eyes locked on her sons. And Matthew saw it. The realization, the horror, the question that would haunt him forever.

How could you, Mom? Wait. But she was moving toward him. Her hands reaching out. Whether to comfort or to take the gun, he’d never know. The second shot happened so fast he barely registered pulling the trigger. Rebecca fell without a sound, her body crumpling beside her husband’s, and the cellar went silent.

“I didn’t mean to shoot her,” Matthew whispered, tears streaming down his face. “She was just she was there and I panicked and he broke off, covering his face with his hands. I killed them both. I killed my parents.” Miller sat back slightly, giving him space, her pen moving across the legal pad in slow, steady strokes. What did you do after? Matthew wiped his eyes, his voice hollow.

I wrapped them in tarps from the garage. I dragged them to the far corner of the cellar. I dug a shallow grave in the dirt. It took hours. When I was done, I mixed the cement Dad had bought for the pipe repair and poured it over them. He laughed bitterly, a broken sound. He had already done half the work for me.

And then I cleaned the gun, put it in the grave with them. I went upstairs, washed my hands, changed my clothes. I sat in the living room until morning trying to figure out what to do. Did you call anyone? I called Linda. Sunday night after I drove back to Moscow, I told her. He stopped, his voice catching. I told her there had been an accident, that I needed her help.

In a separate interview room three floors below, Linda Harrington sat across from another detective. Her face stre with tears. “He told me they were gone,” she said quietly. “He didn’t say how, not then. He just said he needed me to go to the house before anyone else did to make it look normal.” And you did. I did. Linda’s hands twisted in her lap. I cleaned the kitchen.

I locked the doors from the inside. I made sure everything looked like they just stepped out for a moment. I thought I told myself I was protecting him. That he was scared. That he’d made a mistake and I could fix it. Did he tell you what really happened? Linda closed her eyes. Not for years, but I knew. I think I always knew.

Back in the interview room, Miller closed her notepad and leaned forward, her elbows resting on the table. Her voice was quiet, almost gentle. Matthew, I need to ask you something. After you buried them, after you covered it all up, you went back to school. You went to class, you lived your life.

How? Matthew looked up at her, his eyes red and hollow. I was afraid if I stayed, if I acted different, someone would know. So I pretended everything was normal. And after a while, pretending became easier than remembering. For 45 years. For 45 years. He stared at the table, his voice barely audible. I thought burying them would bury the truth. Miller reached forward and pressed the button on the recorder.

The red light blinked once, then went dark. The room fell into a heavy, suffocating silence. Matthew sat motionless, staring at his hands. The same hands that had pulled the trigger, that had dug the grave, that had carried the weight of two lives for nearly half a century. Miller stood slowly, gathering her files. She looked down at him one last time, her expression unreadable.

The truth, she said quietly, doesn’t stay buried forever. She walked out, leaving Matthew alone in the gray room. The fluorescent light humming overhead the ghosts of October 12th, 1973 finally laid bare. The Ada County Courthouse in Boise was built in the 1970s. A utilitarian structure of concrete and glass that had witnessed decades of human tragedy distilled into testimony and verdict.

On the morning of February 4th, 2019, the main courtroom was filled to capacity. Reporters, spectators, residents of Cedar Ridge who’ driven the 2 hours to see justice finally served. The air was heavy with anticipation, thick with the weight of 45 years compressed into a single moment. Matthew Turner sat at the defense table in a gray suit that hung loose on his frame, his hands folded on the polished wood surface.

He looked smaller than he had during the interrogation, diminished somehow, as if the confession had taken something vital from him. His attorney, a public defender named Rachel Moss, sat beside him, her expression professionally neutral. 15 ft away, Linda Harrington sat at her own table, flanked by her lawyer.

She wore a navy dress and a string of pearls, her gray hair neatly styled, her hands clasped tightly in her lap. She hadn’t looked at her brother since entering the courtroom. Judge Margaret Caldwell, a stern woman in her early 60s with steel gray hair and wire- rimmed glasses, presided from the bench. She surveyed the courtroom with the calm authority of someone who had seen every permutation of human weakness and was no longer surprised by any of it.

The state of Idaho versus Matthew James Turner. She announced the defendant is charged with two counts of secondderee murder in the deaths of James Robert Turner and Rebecca Anne Turner. The trial lasted 3 weeks. The prosecution, led by Deputy District Attorney Mark Brennan, built its case methodically, brick by brick, witness by witness. Dr.

Lena Ortiz took the stand first, her testimony precise and clinical as she described the forensic examination of the remains, the gunshot trauma, the positioning of the bodies, the evidence of close-range fire. She presented photographs that made several jurors look away, skeletal remains laid out on steel tables, the rusted revolver, the wedding ring with RT engraved on its interior.

Based on the forensic evidence, Ortiz said calmly. I conclude that both victims were shot in the cellar of their home and buried immediately thereafter. The concrete poured over the grave site was consistent with cement mix available in 1973. Next came the DNA evidence. A forensic geneticist named Dr.

Paul Hang explained in painstaking detail how DNA profiles had been extracted from the revolver’s grip and matched to Matthew Turner with 99.96% certainty. There is no reasonable doubt, Dr. Hang testified, that Matthew Turner handled this weapon. The ammunition receipt from Barlo Hardware was entered into evidence, Matthew Turner’s signature visible in faded ink, dated October 10th, 1973.

The store owner’s son, now in his 60s, testified that his father had kept meticulous records and that the handwriting matched the signature card on file. One by one, the pieces fell into place. On the eighth day of trial, Detective Sarah Miller took the stand. She wore a dark suit, her hair pulled back, her demeanor calm and measured.

Brennan led her through the investigation step by step. The discovery of the remains, the forensic analysis, the interviews with Matthew and Linda, the contradictions in their statements. Detective Miller, Brennan said, “In your professional opinion, what happened on the night of October 12th, 1973?” Miller looked directly at the jury. Matthew Turner shot and killed his father during an argument in the cellar.

When his mother came downstairs and witnessed what had happened, he shot and killed her to prevent her from calling for help. He then buried both bodies beneath the cellar floor and poured concrete over them to conceal the crime. And his sister, Linda Turner, now Linda Harrington, assisted in staging the scene to appear as a voluntary disappearance.

She helped help the door from the inside and clean evidence that might have led investigators to suspect foul play. Why do you believe they remained silent for 45 years? Miller paused, choosing her words carefully. Fear, shame, self-preservation. When you commit an act like this, especially at a young age, the instinct is to bury it literally and figuratively. And the longer you stay silent, the harder it becomes to speak. The lie becomes your life.

The courtroom was silent. The defense tried to argue diminished capacity, emotional distress, the impulsiveness of youth. Matthews attorney painted a picture of a young man under immense pressure, a father who was overbearing and dismissive. A moment of tragic miscalculation that spiraled out of control.

“My client has carried this burden for 45 years,” Rachel Moss told the jury, her voice impassioned. “He has lived every single day knowing what he did. That is a prison sentence in itself. But the prosecution’s rebuttal was swift and devastating. This was not an accident, Brennan said, his voice cutting through the courtroom. Matthew Turner went upstairs, retrieved a loaded firearm, returned to the cellar, and shot his father.

When his mother screamed, he made a choice, a conscious, deliberate choice, to silence her permanently. Then he buried them, poured concrete over their bodies, and went back to college. He attended classes. He lived his life and he said nothing. Brennan paused, letting the words settle.

Justice may be delayed, but it cannot be denied. On February 28th, 2019, after 11 hours of deliberation, the jury returned. The courtroom fell silent as the four person stood. a middle-aged woman with kind eyes and a somber expression in the matter of the state of Idaho versus Matthew James Turner on the charge of seconddegree murder in the death of James Robert Turner. How do you find guilty? A murmur rippled through the gallery.

On the charge of seconddegree murder in the death of Rebecca Anne Turner, how do you find guilty? Matthew’s head dropped. His shoulders shook silently. Beside him, Rachel Moss placed a hand on his arm, but he didn’t respond. Linda’s trial was shorter, 3 days.

The charge was conspiracy to obstruct justice and accessory after the fact. The evidence was overwhelming. Her own statement, the forensic timeline, the locked doors. On March 15th, she was found guilty on all counts. At sentencing, Judge Caldwell addressed both defendants separately. Matthew was sentenced to 40 years in state prison.

Linda received 15 years with eligibility for parole after 10. This case, Judge Caldwell said, her voice measured, represents a profound failure of conscience. For 45 years, James and Rebecca Turner lay beneath the floor of their own home, denied dignity, denied justice, while their children built lives on a foundation of silence. That silence ends today.

She struck her gavvel once and it was over. Detective Sarah Miller stood on the courthouse steps as the crowd dispersed, the winter wind sharp against her face. A reporter approached, microphone extended. Detective Miller, how does it feel to close a case this old? Miller considered the question.

It feels like keeping a promise to the victims, to the community, to everyone who never stopped wondering what happened. “Do you think justice was served?” “Justice is never perfect,” Miller said quietly. “But yes, it was served. In the months that followed, the farmhouse on Old Pine Road was condemned. The county deemed it structurally unsound, its foundation compromised by the excavation.

In late spring, a crew arrived to fill the cellar with concrete, sealing it permanently. By summer, the house was demolished, reduced to rubble and memory. The land was sold to a conservation trust and designated as open space.

Wild flowers grew where the house once stood, and in the evenings, deer grazed in the fields that stretched toward the treeine. Cedar Ridge moved on, quieter now, its most haunting mystery finally resolved. At the community church, a small memorial plaque was placed near the entrance. In memory of James and Rebecca Turner, 21, 1973, 1925, 1973, found, remembered, at peace. On a cold December evening in 2019, Sarah Miller returned to Cedar Ridge.

She drove slowly down Old Pine Road, past the empty lot where the Turner farmhouse had stood, and parked near the river. The clear water moved dark and swift beneath the winter sky, its surface reflecting the fading light. She stood there for a long time, hands in her coat pockets, listening to the wind move through the pines.